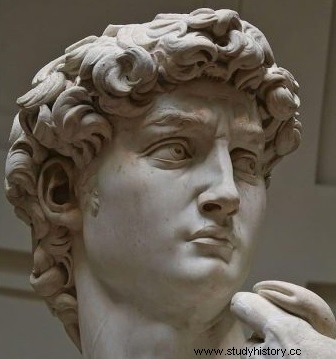

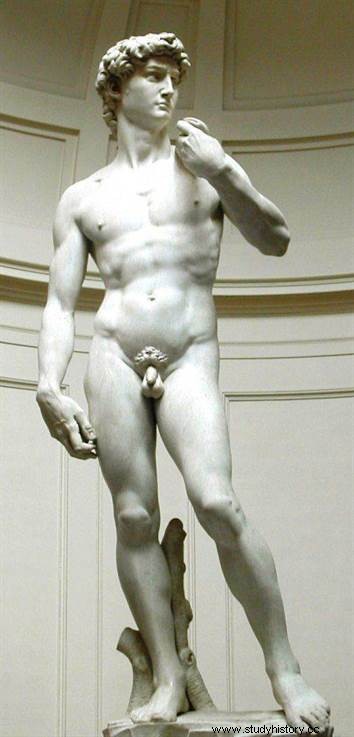

Carved in marble, the David is a statue of more than four meters, made by Michelangelo between 1501 and 1504. A work of the Renaissance, he is the incarnation of the ideal of the man of the time:a perfect aesthetic like the statues of Antiquity, but also a citizen-warrior who puts his strength in the service of his State (here, the city of Florence). Michelangelo's David is kept at the Accademia Gallery in Florence (Italy).

Carved in marble, the David is a statue of more than four meters, made by Michelangelo between 1501 and 1504. A work of the Renaissance, he is the incarnation of the ideal of the man of the time:a perfect aesthetic like the statues of Antiquity, but also a citizen-warrior who puts his strength in the service of his State (here, the city of Florence). Michelangelo's David is kept at the Accademia Gallery in Florence (Italy).

The Sculptor's Puzzle

In March 1501 there was in the city of Florence a gigantic block of Carrara marble which attracted the covetousness of sculptors and always ended up discouraging them as was the case with Agostino di Duccio (in 1463-1464) and Antonio Rossellino (in 1476). The municipality considered putting an artist back to work on this block to make a monumental statue for a flying buttress of the Duomo of Florence Cathedral. After working in Rome and Siena, Michelangelo returned to Florence to take up this challenge:in August 1501, he signed a contract with the guild of wool workers providing for the execution of an imposing statue in two years.

Michelangelo gets to work, he is said to have made a scale model of the work in wax, the would have immersed and would have sculpted the block by taking as a model the emerged part (always larger) of its prototype. He would have made a sprinkler system to limit the dust. Visitors would have reproached him for the accentuated features of the face of his statue, but these were justified in Michelangelo's mind by the height at which his colossus should be placed. The work was not finally completed until 1504. Michelangelo took up the challenge with genius, reworking this block roughed out by his predecessors, he produced a masterpiece, the first colossal nude (more than 4 meters in top), in a single block and without the slightest addition, the only one then known from the works of antiquity. Proud of his work, the artist writes on a study sheet (kept in the Louvre):“What David did with his sling, I, Michelangelo, did with my bow> .

Michelangelo gets to work, he is said to have made a scale model of the work in wax, the would have immersed and would have sculpted the block by taking as a model the emerged part (always larger) of its prototype. He would have made a sprinkler system to limit the dust. Visitors would have reproached him for the accentuated features of the face of his statue, but these were justified in Michelangelo's mind by the height at which his colossus should be placed. The work was not finally completed until 1504. Michelangelo took up the challenge with genius, reworking this block roughed out by his predecessors, he produced a masterpiece, the first colossal nude (more than 4 meters in top), in a single block and without the slightest addition, the only one then known from the works of antiquity. Proud of his work, the artist writes on a study sheet (kept in the Louvre):“What David did with his sling, I, Michelangelo, did with my bow> .

Michelangelo's masterpiece exalting civic virtues

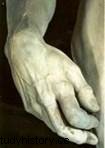

David, biblical hero king of Israel but above all young shepherd who conquered the terrible Goliath. It does not depict him in the fury of battle, nor triumphant over his adversary's remains (as is the case with Donatello's David putting his foot on his enemy's head). On the contrary, he chooses the crucial moment which precedes the action and where all of David's tension is felt, first and foremost in the position of the hands, the prominent veins, the irritated forehead, but also in the determination of his gaze... The David by Michelangelo is a dynamic captured in this moment of latency which precedes its unleashing. Everything is tension.

David, biblical hero king of Israel but above all young shepherd who conquered the terrible Goliath. It does not depict him in the fury of battle, nor triumphant over his adversary's remains (as is the case with Donatello's David putting his foot on his enemy's head). On the contrary, he chooses the crucial moment which precedes the action and where all of David's tension is felt, first and foremost in the position of the hands, the prominent veins, the irritated forehead, but also in the determination of his gaze... The David by Michelangelo is a dynamic captured in this moment of latency which precedes its unleashing. Everything is tension.

But the work does not only have a Christian illustrative vocation, this ancient body (reminiscent of Hercules, hero protector of the city) and this biblical theme have a civic intentionality . The image of David exalts what the Renaissance considered to be civic virtues:Strength and Anger intimately linked to the idea of defending republican freedoms. Forehead and hands are subject to the same tension leading to a physical and moral glorification of the citizen. The latter is characterized by dominated muscular torsion and spiritual tension expressing the hero's control over his own destiny.

In June 1504 the cathedral authorities appointed a commission to decide on the location of the colossus. This commission is made up of illustrious artists including Botticelli, Filippino Lippi and Leonardo da Vinci. It then seems clear to the members of the commission that the place of this statue is not on the cathedral but on the public square, in front of the palace of the Signoria (Palazzo Vecchio ), to replace the Judith by Donatello. After having chased away (thanks to the French invasion) the despotism of the Medici, then the religious intransigence of Savonarola, the small Florentine republic exposes its avatar for all to see.

Michelangelo and the David:the ambiguity of a relationship with the Medici

The David is a pro-republican work and therefore goes against the power of the Medici family over Florence. The political use of his work places Michelangelo in the wrong with this family where he grew up. Indeed he had been noticed by Laurent the Magnificent who had taken care to integrate the young man into his own family as a good paternal patron. But the successors of Laurent and their political choice had not satisfied Michelangelo, now anxious to show his rallying to the Republic. The rest of his career will be marked by a succession of more or less desired works on behalf of the Medici family who have come to the pontifical dignity.

It is moreover with the support of Pope Julius II (for whom Michelangelo works) that the The Medici returned to the Florentine political scene in 1512. But following the sack of Rome by Charles V in 1527, the Florentine people revolted and chased the Medici away again, playing support for France. Besieged in the palace of the Lordship the rebels throw various objects at their attackers, one of these improvised projectiles hits the David, breaking his left arm. The pieces would have been recovered by a certain Vasari. The latter will then enter the service of Cosimo I de Medici, new duke, and will restore the David to renew (in a unilateral way) the link between the Medici family and the illustrious artist adopted by Lorenzo the Magnificent.

It is moreover with the support of Pope Julius II (for whom Michelangelo works) that the The Medici returned to the Florentine political scene in 1512. But following the sack of Rome by Charles V in 1527, the Florentine people revolted and chased the Medici away again, playing support for France. Besieged in the palace of the Lordship the rebels throw various objects at their attackers, one of these improvised projectiles hits the David, breaking his left arm. The pieces would have been recovered by a certain Vasari. The latter will then enter the service of Cosimo I de Medici, new duke, and will restore the David to renew (in a unilateral way) the link between the Medici family and the illustrious artist adopted by Lorenzo the Magnificent.

"There is no doubt that, of all modern and ancient works, Greek or Roman, Michelangelo's David wins the palm. Once you have seen it, it becomes useless to look at another sculpture or the work of another artist”. This is how Vasari spoke of the masterpiece sculpted from 1501 to 1504 by the illustrious Michelangelo, a work inspired by the Bible and Antiquity to better exalt the civic virtues of the Florentine Republic.

The David can now be seen at the Galleria dell'Accademia in Florence.

To go further

- Michelangelo. Complete painted, sculpted and architectural artwork. Taschen, 2017.

- Florentine Renaissance sculpture, by Charles Avery. Paperback, 1996.