Pork chop with potatoes? Tomato soup? Or maybe a strawberry compote? Forget it. The Middle Ages were completely unfamiliar with these typically Polish dishes. And not only them!

1. Forget potatoes

The potatoes were brought to Europe from the Inca state conquered by the conquistadors in the 16th century. So it is in vain to look for potatoes on medieval tables. Instead of them, groats reigned!

In our part of the continent, potatoes first became popular in ancient Prussia, when in the 18th century Frederick the Great ordered their cultivation, threatening to cut the noses of the disobedient subjects. It was not for nothing that Poles called the Germans potato farmers. And today it is difficult to imagine Polish cuisine without potato dishes - in Biesiekierz near Koszalin, even a Potato Monument was erected.

2. Pork chop from export

Our pork chop is a cheaper, pork version of the Viennese schnitzel, made of veal. It became popular in the 19th century. In medieval courts it would hardly be considered a delicacy. "Boar heads, venison, peacocks, swans, pigs, cranes, plovers and larks were served at feasts," write Joseph and Frances Gies in the book "Life in a Medieval Castle".

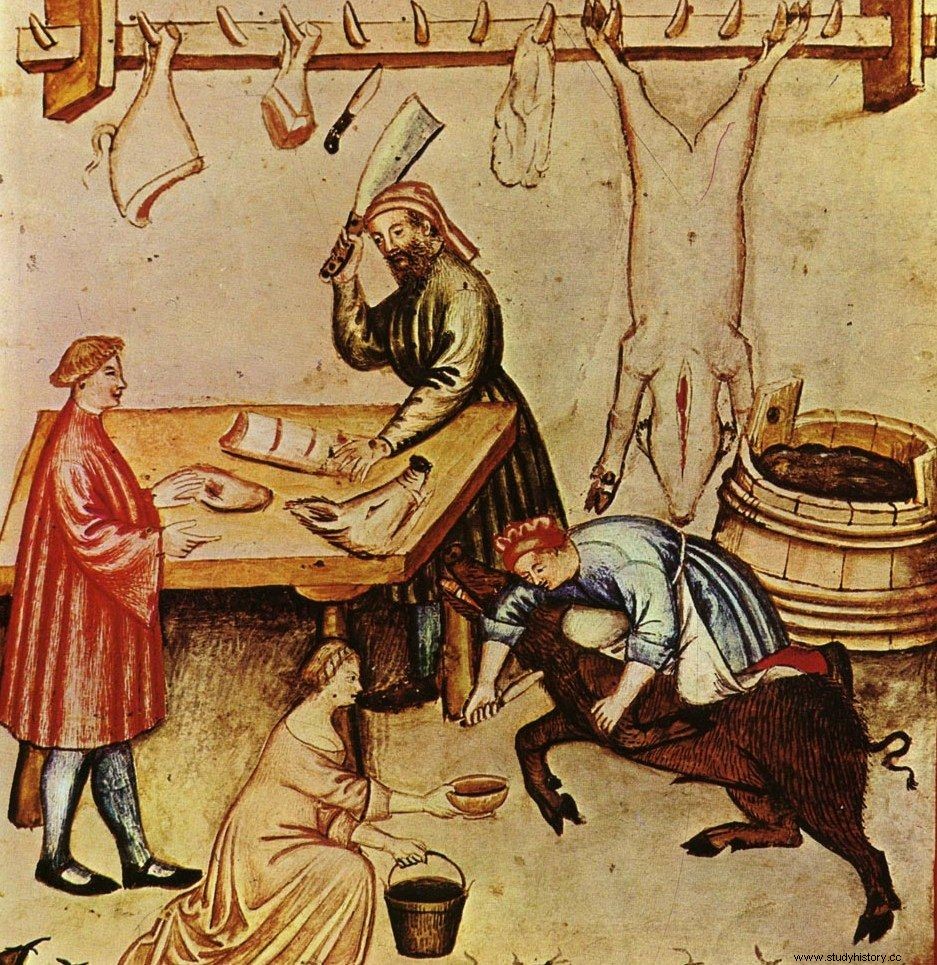

Pork was eaten in the Middle Ages, although it was not very valued. And it was certainly not eaten in the form of pork chop! Illustration from the 14th-century healthy lifestyle textbook "Tacuinum sanitatis".

3. No tomatoes!

Tomatoes came to Europe, and more precisely to Spain, only at the beginning of the 16th century with sailors returning to Seville from the New World. They were then called "apples of love" (because they were classified as an aphrodisiac) and "golden apples" (that is, they were slightly different in color from today's).

It was better in the Middle Ages with soup thickeners. Rice was already known, brought south by the Arabs. As for pasta, scientists speculate that it was known in ancient Rome, only later forgotten. It was certainly made in 12th-century Sicily (where Arabs ruled for two centuries), but then it was only a local specialty. It was only in the following centuries that he persuaded not only Italians.

4. Strawberry compote?

The strawberries are the result of an experiment by French botanists in the 18th century. They crossed wild strawberries - virginian with Chilean. Earlier in Europe, our medieval ancestors could only eat wild strawberries.

5. Pizza? For the poor

Various pancakes and flatbreads have been eaten in Europe since ancient times. Cheese, fish etc. was added to them. But what a pizza without tomatoes and bufala cheese! Tomatoes were discovered by Europeans in the New World (see above). mozzarella di bufala campana cheese They are made from the milk of Bubalus bubalis buffaloes (domestic ox), practically unknown in medieval Europe.

6. A bit different borscht

Incredibly, our ancestors did not eat in the Middle Ages also the borscht we know today - made from beetroot. Originally, a dish with this name was made from the borscht plant. The dish gained popularity in Poland, Lithuania and Russia. This is how Marcin from Urzędów praised this soup in the 16th century:"Drink with fever, fever, and thirst, because thirst and cola are calmed, and greed with its spice".

Was borscht being cooked here? Even so, it is definitely not beetroot! The woodcut is from "Kuchenmaistrey", the first cookbook to be printed in Germany published in 1485.

7. Turkey breast in chocolate

The recipe for this dish can be found on many websites today. Of course, there was no internet in medieval Poland, and there was also a shortage of basic products for this dish. The turkeys were only brought to Europe from the New World. It started with Spain, and in Poland this poultry spread several decades later - around 1560 as an "Indian hen" ( gallus indicus ).

It was the same with chocolate. Cocoa seeds caught the attention of Cortes during the conquest of Mexico. They served the Aztecs as a means of payment, and they were also used to prepare a ritual drink. In Europe, this drinking chocolate first conquered Spain, and in 1615 it became the official drink of the French court. However, it was not until the 19th century that chocolate bars began to be made.

Chillies and allspice (contrary to the misleading name) also come from the New World - needed to cook a turkey in chocolate. No wonder the term "Mexican" is sometimes added to this dish.

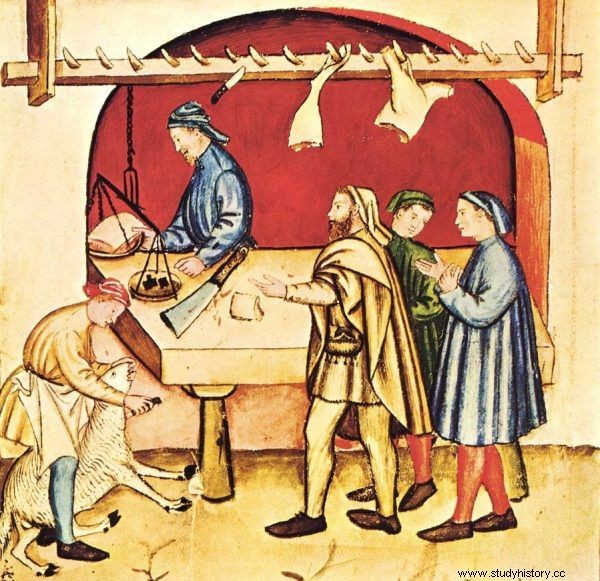

In medieval meat, it was impossible to get turkey breasts. Illustration from the 14th-century healthy lifestyle textbook "Tacuinum sanitatis".

8. Coffee or tea

There was no such choice in medieval Europe. You just didn't drink one or the other! Coffee comes from Ethiopia, associated with the legendary Kingdom of Priest John, which is to help Christians in crusades against Muslims. However, it came to Europe through the followers of Allah and not in the Middle Ages, but later.

The first coffee shop was opened in Istanbul (1554). Then, from the Ottoman Empire, coffee went north and west. It came to Poland after the triumph of Jan III Sobieski at Vienna (1683). Dutch merchants trading with distant lands also had their share in the dissemination of coffee.

And it is also thanks to the Dutch, as well as the English and Portuguese that tea came to Western Europe from Asia in the 16th century. Our eastern neighbors also contributed to its popularity. In the 16th century, tea was brought to the Moscow state - from China.

9. Ice cream only in Arabic

Ice cream for dessert? Not in medieval Christian Europe! Yes, in the then Sicily, the Arabs introduced the art of preparing sorbets:from juices mixed with snow from the mountains (by the way, similar recipes were known by the ancient Greeks and Romans, but it was forgotten). However, on the continent, this delicacy spread much later, in the Renaissance.

Besides, sorbets are not ice cream! Real ice cream, prepared with the use of cream and butter, appeared at courts only in the 17th and 18th centuries.

10. The vodka problem

Nothing but this medieval poverty to drink vodka! But that will also be a problem. The process of alcohol distillation was invented by the Islamic alchemists in the 9th century or Italians three centuries later. Anyway, it resulted in high-percentage alcohol, which in Europe was called "the water of life" ( aqua vitae , Polish "okowita"), because he was credited with healing properties.

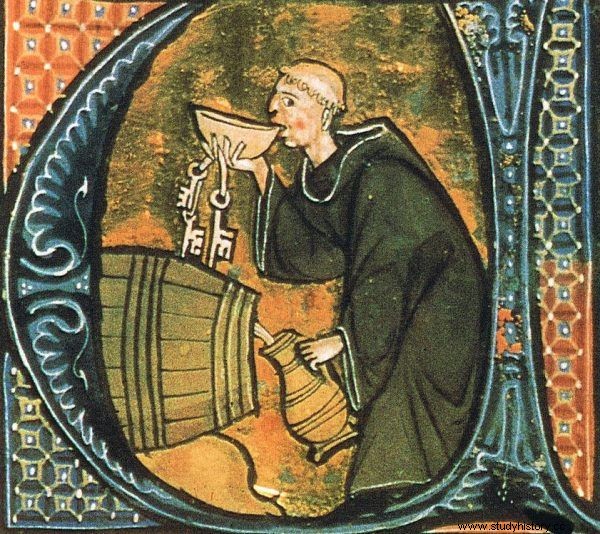

Since there was no vodka, sorrows were drunk with wine. In this 13th-century illustration from Aldobrandin's Lives of the Saints, we see an abbot testing the drink.

The name "vodka" was used for the first time in the Sandomierz town records in 1405, but it also referred to substances considered to be medicines. In the face of strong alcoholic beverages, the term "booze" was first used. However, the dynamic production of this alcohol did not take place in the Middle Ages, but only in the 16th century.

Not that the Middle Ages were the age of sobriety. You just drank something else. Wine, honey and beer poured in streams. The slogan "beer in the morning like cream" was very much in use. "After the morning mass in the chapel, the family sat down to breakfast, which consisted of bread washed down with wine or ale" - describe life in a medieval English castle, Joseph and Frances Gies.

However, in our Polish backyard, Prince Leszek the White (1184–1227) himself avoided going on a Crusade, explaining to the Pope that there was no beer in the Holy Land, and he could not live without it ...

Bibliography:

- Bryan Bruce, Taste Story , crowd. Ewa Kleszcz, Warsaw 2009.

- Maria Dembińska, Food consumption in medieval Poland , Wrocław 1963.

- Jarosław Dumanowski, The first steps of a turkey in Poland, Wilanów Palace.

- Joseph and Frances Gies, Life in a Medieval Castle , crowd. Jakub Janik, Krakow 2017.

- Piotr Kałuża, Inventions from the East , Focus Historia Ekstra nr 1/2017.

- Lapham's Quarterly:Food , vol. 4, No. 3/2011.

- Jarosław Molenda, History of edible plants , Warsaw 2014.

- Henryk Samsonowicz, Sketches about the Medieval City , Warsaw 2014.

- Mary Ellen Snodgrass, Encyclopedia of Kitchen History , New York 2004.