Not every marriage turns out to be a good one. The ancient Romans knew this well, for whom divorce was a common practice.

In Greece, the law required her husband to separate from his wife if she had committed adultery. In addition, however, the Greeks allowed divorce for other reasons, such as the inability to have a child. Theoretically, the initiative was on the side of both men and women. In practice, a wife could only count on divorce if she was abused and the family wanted to support her. Which was rarely…

Not every marriage turns out to be a good one. The ancient Romans knew this well, for whom divorce was a common practice.

No wonder it ended with threats rather than breakups. For example, in the 5th century B.C. the wife of a Greek statesman and adventurer, Alkibiades, tried to break up with him for constantly bringing prostitutes home. The latter, however, forced her to return. During the domination of Rome, the question of divorce was completely different.

Wife's baton

The Romans were guaranteed the right to divorce already on the basis of regulations attributed to Romulus, the legendary founder of the city. It allowed a man to dismiss his spouse in the event of committing adultery, child stripping and ... misappropriating the keys.

According to the researchers, "stress" actually means an abortion that would be an attack on the husband's rights without the husband's knowledge. The "appropriation of keys" may refer to picking up a locked wine. So the point would be to break the ban on drinking alcohol that used to be in force for women (and maybe even addiction?). Apparently a certain Roman called Egnatius Metellus took a club and beat her to death for his wife drinking wine . Let us add that this drink was also attributed contraceptive and early abortion properties, which constituted an additional "threat" to a man's power.

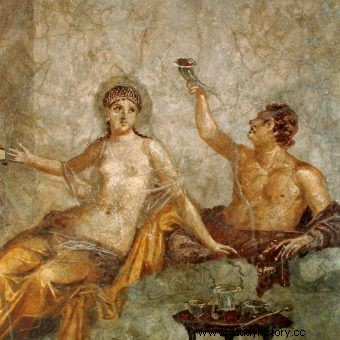

Not so much for attending such a feast as for drinking wine alone, the Roman had the right to divorce his wife. Sometimes, however, he preferred to punish ... Picture by Robert Bompiani.

In the event of divorce for other reasons, the Roman had to pay dearly:to give half of the property to his spouse, and the other half to the goddess of fertility Demeter (Ceres). Not surprisingly, according to Roman tradition, in the five hundred years since the city was founded, there has not been a single divorce there! The first was by a certain Spurius Carvilius Ruga in 231 BCE. And it was not because he did not love his wife. She simply couldn't have children, and he took the customary oath to officials to marry in the hope of having children. Interestingly, his countrymen did not share his opinion. They decided that loyalty to a wife should be above a civic oath.

It is possible that the therapy at the temple of the goddess called Viriplaca (Mitigating Husband's Wrath) helped with marital problems. The quarreling couple was obliged to spend the night in it, reproaching each other's guilt and grievances in front of the altar. Apparently, this method worked wonders. It cleansed the psyche, and at night the seclusion of the temple was conducive to sexual intercourse. Obviously "consent".

To split up to get married

The revolution came when in the 2nd century BC also Roman women gained the right to file for divorce. And when they were allowed to have a greater discretion about their marriage, a wave of moral change ensued. They were no longer at the mercy of men, and they also took advantage of new opportunities. As a result, at the end of the republic and the beginning of the empire, a plague of divorce prevailed in Rome.

Usually they parted in order to… get another wedding right away. It was enough for one of the spouses to declare the breakdown of the marriage and that was done. The wife could have a relationship with a friend of the house, the husband with a friend (sometimes women were even passed on to each other!). The couple had to declare that they were in a relationship - and they were already married. She could also organize a banquet and take part in traditional ceremonies. The state had little to say. In 19 BCE Consul Quintus Lucretius Wespillo said directly during his wife's funeral:

It is rare today a marriage like ours that was broken by death, not divorce; we were so lucky - we lived forty-one years without arguing .

Knowing from life practice that usually in the event of a breakup, neither side is without fault, the philosopher Seneca the Younger preached in the first century CE. something like the idea of symmetrical marital fidelity. Until then, a rare thing in Rome. “You know that it is a wicked man who demands decency from his own wife, and that he himself is a seducer of other wives. You know that just as she should have nothing to do with the adulterer, you must stay away from the harlots, "he said.

Even the reforms of Octavian Augustus himself did not end the scourge of divorce in Rome ...

Emperor Octavian Augustus wanted to remedy the breakdown of relationships by issuing special marriage laws. They stigmatized adultery (although at the same time deprived the husband of the right to kill an unfaithful wife and limited the possibility of punishing her seducer with death), imposed the obligation to stay married on Romans aged 25-60 and Roman women aged 20-50, and encouraged Roman citizens to beget children.

However, neither the threats nor the peculiar 500+ Augusta program (based on tax exemptions) healed the customs and did not cause baby boom and so is the levying of a special tax on old bachelors . Men were neither able to resist temptation nor were they able to control their women anymore - and the aspirations of the latter were starting to change.

***

The text was created during the author's work on his latest book. " Ages of shame. Sex and erotica in antiquity ” .

Bibliography:

- Mary Beard, SPQR. History of Ancient Rome , crowd. Norbert Radomski, Rebis 2016.

- Peter Connolly, Hazel Dodge, Ancient cities:architectural wonders, social, cultural and religious life , crowd. Barbara Tkaczow, RTW 1998.

- Aulus Gelliusz, Attic Nights , in:Lidia Winniczuk, Women of the Ancient World. A selection of texts by Greek and Roman authors , PWN 1973.

- Sławomir Koper, Private and erotic life in ancient Greece and Rome , Bellona 2011.

- Seneca, Moral Letters to Lucylius , in:Michel Foucault, A History of Sexuality , crowd. Bogdan Banasiak, Tadeusz Komendant et al., Wydawnictwo świat / obraz Klimatyzacja 2010.

- Andrzej Wypustek, Family Life of the Ancient Greeks , National Institute for them. Ossoliński 2007.

- John G. Younger, Sex in the Ancient World from A to Z , Routledge 2005.