Bolesław Śmiały (Szczodry) dreamed of rebuilding Poland's position in the times of his great-grandfather - Bolesław the Brave. Generous, ambitious, but at the same time proud, impetuous and cruel ruler, before he finally lost everything as a result of the murder of the bishop of Krakow - Stanisław and his escape from the country, he successfully meddled in the affairs of his neighbors, pursuing his superpower policy. He went, among others to Rus, where he placed his protégé Izjasław on the throne. This expedition, however - according to the chronicler - was not a success, but a scandal. Here the warriors of Bolesław suddenly left the king and fled to Poland. Why did they desert? It is said that when they fought alongside the ruler, their wives enjoyed carnal pleasures in the arms of others ...

A report on this subject, about 130 years after the described events, was left by the Bishop of Krakow, Wincenty Kadłubek. According to the chronicler, Bolesław's warriors were to lose their will to fight and conquer when the news of their wives' exploits reached them ...

When the king stays in the Ruthenian lands for a very long time, the servants almost persuade the wives and daughters of their masters to succumb to their lusts, apart from the seats of the Parthians. Some are tired of waiting for their husbands, others are driven to despair, some are caught by violence into domestics. - the chronicler recalled.

What punishment was to be faced by unfaithful wives?

The ruler's revenge was terrible. After his return to Poland, Bolesław dealt not only with the disloyal knights who had abandoned him during the expedition, but also with their slutty wives.

(...) even those women whose husbands forgave him, he persecuted with such horror that he did not hesitate to attach puppies to their breasts, after throwing off the babies

- reported Wincenty Kadłubek.

Bolesław II the Bold, lithograph by W. Walkiewicz based on a drawing by Aleksander Lesser.

The king's gesture was a symbolic display of disrespect to women. He likened them to animal females. Did such humiliating scenes take place in the Piast country? Although Master Wincenty's account is at least a colored version of events, made of scraps of information, historians do not deny it a "grain of truth". As a result of Bolesław's frequent war expeditions, his state was in a deep crisis. The ruler did cruelly silence the disloyal knights and the powerful. The aftermath of the conflict over the Kiev expedition was the king's loudest crime - the murder of Stanisław, the bishop of Krakow.

So what really happened in 1077, during Bolesław's expedition to Ruthenia, which was probably the catalyst for the subsequent fall of the king and the entire state?

Distribution and warrior

Already from the account of Bishop Gall Anonymus, who wrote his chronicle some 40 years after the rule of Bolesław, a picture of a ruler full of extremes emerges. On the one hand, he seemed to be a good-hearted man. He was nicknamed "generous", which meant that he liked to show his generosity - bestow deservers, supporters and the church with various donations, riches, earthly goods, etc. he founded and richly equipped the monastery in Mogilno, he also rebuilt the cathedral in Gniezno, which was destroyed as a result of the Czech invasions.

On the other hand, the same chronicler, who was the most balanced of all historians dealing with the figure of Bolesław the Bold, only stated that the ruler was characterized by "a certain excess of ambition and vanity."

It was probably the latter trait of character that drove the militant Bolesław to constant expeditions against his neighbors. The scale of military interventions could be compared to his great-grandfather - Bolesław the Brave himself. He intervened twice in Hungary, where he placed his supporter Bela I and later Władysław on the throne, made Pomerania again dependent on the state, refused to pay tribute to the Czechs and fiercely fought with his southern neighbor. He assembled an anti-German coalition and, in support of the Pope, he mocked his dependence on the empire. Finally, he made two trips to Kievan Rus.

Bolesław the Bold organized many military expeditions

The first time - in 1069, Bolesław placed Izjasław, the husband of his aunt Gertrude, on the throne in Kiev.

For the Bold, entering Kiev was undoubtedly a confirmation of his strong position. He did what Bolesław the Brave did several decades earlier. By the way, he did not forget to mention who really is in charge here. He publicly humiliated Izjasław, who was seated on the Russian throne. Instead of exchanging kisses with him - which was a sign of the rulers' mutual respect - Bolesław did not even get off his horse. Izjasława, on the other hand, publicly pulled his beard - which was a clear sign of his disrespect and superior position towards the Russian partner.

The result of the expedition, apart from strengthening the prestige and sphere of influence, was of course also loot. Kyiv was then one of the richest cities in Europe. There was something to loot. Rich gains guaranteed loyalty in the ranks of warriors and closed the mouths of those who could question the ruler's decision.

Empty money

The politics of warfare and financial momentum worked for a long time, and finally something jammed in it. The country found itself at an economic turn, after Bolesław Szczodry founded the crown in 1076. War and other expenditures did not balance with possible profits. In the cash register of the lavish and impetuous state, Bolesław started to glow empty.

The currency minted by the king was legible evidence. While before the coronation, the denarii of Bolesław the Bold (he resumed the issue initiated by Brave) had about 20 percent. silver, after the coronation, the share of the precious metal decreased drastically, in favor of much less valuable copper.

The royal denarii of Bolesław the Bold contain extremely little silver, and the latest issues are almost copper. It can be assumed that this monetary fraud was one of the reasons for the resistance of the population against the ruler, which consequently led to his removal from the throne

- writes archeology and numismatist, prof. Stanisław Suchodolski.

The awareness of the poverty of society, especially the aristocracy, for which it was of particular importance whether they store copper or silver in their vaults, was certainly fertile ground for rebellion.

Moreover, frequent expeditions (in 8 years from 1069 to 1077 he set off with at least four military interventions - to Hungary, the Czech Republic and Ruthenia) could raise resistance to the increasingly weary knights, especially when the promised loot was lacking.

This was the case during the second expedition to Ruthenia in 1077, undertaken to re-appoint Izjasław. It was then that some of the king's warriors refused to obey him and deserted, returning to their homeland. Why did this happen? Today one can only speculate.

Perhaps they were indeed afraid of "possessions," not even of wives, but rather of land, positions, and estates. If a revolt broke out in the country, the long absence of Bolesław's knights could contribute to the consolidation of new orders introduced by the rebels. Certainly more than one guardian of the knight's property in the Lord's absence wanted to take over both the land and the treasures of his wife ...

In such a system, warriors were likely to want to return to save their own possessions and power - especially if the war gains turned out to be poor. It is possible that some deserters took the side of the rebels. These, in turn, could have had enough of a tyrant on the throne, with an exuberant ego strengthened by a crown, who was ruining the country economically. It is also possible that the soldiers tired of fighting decided that fighting far from home simply did not pay off.

Pride before the fall

Anyway - as a result of the king's expeditions, but also Bolesław's bloody settlements and settlements with deserters, the rebellion in the country intensified even more. Today, most historians are inclined to the thesis that against this background there was a conflict and, as a result, the murder of St. Stanislaus. Probably the bishop was one of the leaders of the rebellion.

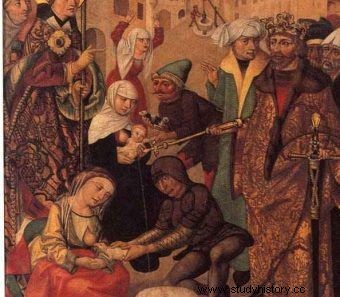

Death of Bishop Stanisław in the painting by Aleksander Augustynowicz. In fact, the death of the future saint must have been different.

Was it really so? According to Gall Anonymus, Stanisław was guilty of a betrayal. He could take the side of persecuted warriors, or maybe he was guided by his own ambition and was looking for supporters abroad? His position as the bishop of Kraków weakened when Bolesław the Bold restored the Gniezno metropolis.

Despotic actions and bloody punishment on the clergyman did not, however, alleviate the unrest in the Piast state. Bolesław the Bold had to flee abroad. He fled to Hungary with his wife and son. He sought support from his supporter, King Władysław, whom he himself helped to put on the throne. What happened next? Unfortunately, until the end of his life, the dethroned ruler could not overcome the limitations of his own character. He continued to be proud and haughty, as if he was the one dealing the cards, even though he was fully dependent on his tutors abroad. T in turn was to cause the mighty Hungarians to turn away from him. Bolesław died in unexplained circumstances around 1081-1082. Presumed murdered.

Bibliography:

- Oswald Balzer, Genealogy of the Piasts, Krakow 1895.

- Norbert Delestowicz, Bolesław II Szczodry. The tragic fate of the great warrior, 1040/1042 - 2/3 April 1081 or 1082, Krakow 2016

- Aleksander Gieysztor, Polish kings and princes, Czytelnik, Warsaw 1980

- Tadeusz Grudziński, Bolesław Śmiały-Szczodry and Bishop Stanisław. History of conflict, Warsaw 1983

- Kazimierz Jasiński, Pedigree of the first Piasts, publ. 2, Poznań 2004.

- Jan Powierski, The Crisis of Bolesław the Bold's Government, Marpress, Gdańsk 1992

- Jerzy Rajman, An outline of the political history of the Polish state Suplement IV, Oxford Educational, Inowrocław

- Stanisław Rosik, Bolesław Szczodry and his times, Wydawnictwo Dolnośląskie, Wrocław 2002

- Krzysztof Skwierczyński, Reception of Gregorian Ideas in Poland. Until the beginning of the 13th century, Wrocław 2005

- Przemysław Wiszewski, Domus Bolezlai. In Search of the Piast Dynastic Tradition (until around 1138), Wrocław 2008

- Tadeusz Wojciechowski, Historical Sketches of the 11th Century, publ. 4, Warsaw 1970