When serfdom was abolished in 1861, 23 million Russians were privately owned by the gentry. The peasants were sold as a living commodity, they were played at cards ...

Behind all, in the last and most distant ranks of the Russian nobility was its most numerous part - the petty nobility. The rules of society meant that she tried to keep pace with the wealthier confreres.

Therefore the owners of not even hundreds, but at most a few dozen "souls" flaunted their high birth and abundance :they bought themselves carriages, the best horses, expensive and sophisticated clothes, although they kept a small service:coachman, butlers. All these whims were paid for with the bloody sweat of the peasants. Mikhail Saltykov Shhedrin wrote:

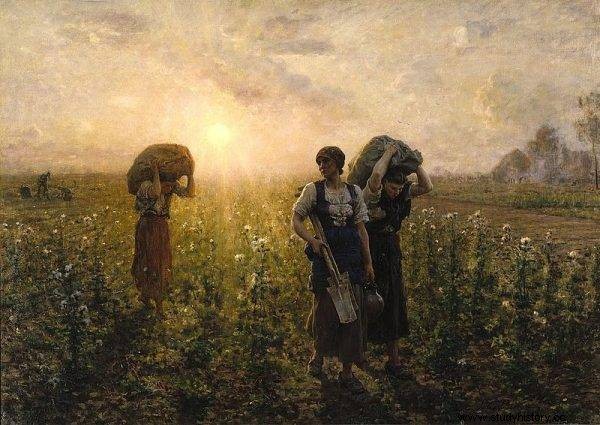

There was complete freedom, hospitality, cheerfulness. Therefore, to satisfy the needs of a boisterous life, the last sweats were squeezed out of the peasants, and the peasants, of course, did not sit with their arms folded but they were bustling like ants in the surrounding fields. […]

The peasant of the small landowner was so exhausted by serfdom beyond his strength that he was easily recognized in a crowd of other peasants. He was more frightened, weaker, weaker and less growing . In a word, in the total mass of exhausted he was exhausted the most.

In many noble folks he worked for himself only on holidays, and on weekdays - at night. So the summer harvest season in the world was simply a real ordeal for these people.

Also read:"Szela damn!". Contempt for the peasant in the Second Polish Republic

One peasant, a few gentlemen

However, the petty nobility also did not make up a homogeneous environment. There was a great social distance between the modest, but making ends meet on his farm, the owner of fifty or a hundred "souls" and the pathetic owner of only a few serfs.

Meanwhile, such nobles, "grays", as they contemptuously called their class-brethren, were abundant in the Russian Empire. In some governorates the number of landowners with no more than twenty peasants was three-quarters of the total number of "souls" owners.

The more and more common impoverishment of the nobility took place as a result of the division of property among the heirs. From the beginning of the nineteenth century, after the nobility ceased to receive the property of the state peasants during the reign of Alexander I, the fragmentation of property became particularly visible.

Some landowners owned a good number of "souls", but scattered around villages.

Initially, it led to a characteristic chessboard, where in the same village or in the same estate a pair of peasant farms belonged to one owner, and the adjacent ones belonged to the other.

Some landowners owned a good number of "souls", but scattered around villages. This made it impossible to create a profitable farm, and the new divisions made the situation even more complicated, which in turn led to the paradox whereby one peasant was obliged to provide for two or more masters, almost like in a well-known fairy tale.

Read also:Was the medieval serf peasant a free man?

"Souls" for sale

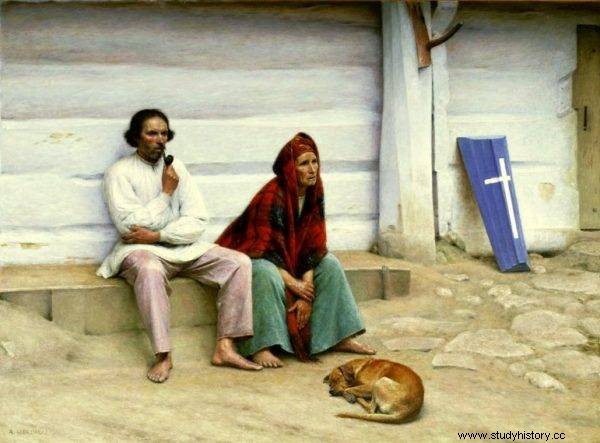

With time, the fragmentation became so great that the landowner's house did not differ from the peasant's, and the landowner himself did not differ from his peasant. Moreover, at the beginning of the 19th century, a considerable number of nobility appeared, both without property and without "souls". Due to the lack of peasants and servants, the nobility worked their own land. Most of the small owners were in the Ryazan Governorate. They were mockingly referred to as "nobles" there.

These nobility sometimes occupied entire villages, their houses stood between peasant cottages, and the size of their land was so small that they could not support even their "noble" family, often very numerous. In this situation, neither of them thought about hospitality or visiting their neighbors anymore.

The last peasants, if they still had any, "shaved their heads", that is, they gave them into recruits, or sold them to the landowners from the neighborhood to get even a little money, while they went to the fields themselves, plowed and sowed, harvested.

The text is an excerpt from the book by Boris Kierżeniew "Captive Russia. A history of serfdom ”, which was published by Wydawnictwo Poznańskie.

Others went to the city to earn money. In St. Petersburg and Moscow, one could meet an impoverished nobleman in a hat and a horse-drawn carriage driver, selling hot patties, working physically or having a row in an inn.

Aleksander Koszelow wrote about such nobles that many of them have one pair of shoes at home, which are used alternately between the gentleman and the peasant , depending on the needs, the one who goes somewhere, goes to the forest, etc. puts them on. "A significant part of the petty nobility drives, plows together with their peasants, wears the same caftans, half-sheepskin coats and sheepskin coats".

Read also:Were our great-grandparents slaves? What was the life of serfs really like?

Peasant's house

A typical small noble manor, small and decaying, consisted of two rooms separated by a hallway, with an attached kitchen. However, there were two parts in it:to the right of the "lord's" entrance, to the left of the peasant, thanks to which the class division into masters and slaves continued here, amidst poverty and poverty.

Each of these parts was separated in turn by partitions. Along the walls of the peasant house there were bunks for sleeping, looms, hand burrs. Among the furniture, a roughly hewn table, benches or a pair of chairs, trunks, nurseries and what is needed on the farm.

Along the walls of the peasant house there were bunks for sleeping, looms and hand burrs. Among the furniture, a roughly hewn table, benches or a pair of chairs, trunks, nurseries and what is needed on the farm.

Baskets with eggs were usually stored under the benches, and dogs, poultry, calves, cats and other animals were walking or running around the room, depending on their temperament whose species affiliation could not be determined by the witnesses themselves (...).

Your half was cleaner and neater. The furniture, although old and heavily shabby, remembered better times. In other respects your chamber was not much different from the journeyman chamber.

Quarrels and disputes

One of the typical features of the life of the petty nobility, also characteristic of wealthier noblemen, was a multitude of all kinds of residents and tenants who pressed into their extremely modest household with their hosts . In conditions of real poverty, in tiny rooms and often without eating, there were relatives who could only look for a piece of bread and a shelter in this poor "family nest".

Here you could meet "unmarried cousins, the elderly sister of the host or the housekeeper, or the uncle of a retired cavalryman who was overspending his fortune."

In the cramped and poor household, quarrels and constant resentments took place. The hosts jumped on the tenants, who, not being indebted to them, referred to the old benefits that the present hosts had received from their parents. They invented vulgar, tavern-like ideas, made up, then quarreled again, and the truce hours were diversified by rumors or playing cards.

The poorer the landlord was, the more he sensed the gap between his formal "nobility" and the degrading conditions of existence, the more persistently he insisted on recognizing his class superiority, and reminded of his birth at every opportunity . The pride of the petty nobility was hurt the most by richer and more influential neighbors. The only task they once and for all assigned the "grays" in their courts was to play the role of a jester.

In the cramped and poor household, quarrels and constant resentment took place.

Cruel corporal punishment

They mocked the poverty of "nobles" and the related lack of education, manners and the ability to behave in "noble" company. The vulgar garments, which were a bizarre combination of robes, were mocked at that their fathers and grandfathers had worn in better times.

Some petty landlords were eager to assume the role of a jester, and were good at it, entertaining their patron's guests. On the other hand, those who considered this occupation as degrading preferred not to appear in rich courts (...).

However, the degrading situation of the petty nobility did not make her any more generous with her subjects, and her compulsory living in a cramped environment with the peasants made her even more pride in class. Such a nobleman, after returning home from visiting his neighbors, where he was entertained by the company, exposing his poverty, played himself on defenseless service (...).

For example, a noblewoman from the Smolensk governorate, Łosiewska , punished her maid with her own hand for not being able to perform the duties assigned to her due to illness . Łosiewska locked the girl in a cold cellar and kept her there starving, as a result of which the subject died.

Another landowner decided to "heat up" her slave:Captain Baranów, suspecting the "maiden" serf of theft and trying to convince her to confess, ordered the poor woman to sit on a hot stove (...).

Read also:The peasant will not forgive the living, or a brawl in a medieval village

A rural battlefield

The gendarmerie officer informed his superiors with dissatisfaction and anxiety about his observations of the customs prevailing in the environment of landowners:

Unfortunately, most of our nobility, especially petty ones, due to the lack of education and simple lifestyle in the countryside, so far she had not understood that with gentle persuasion more can be achieved than with constant austerity, and could not do justice except by corporal punishment.

A nobleman, after returning home from visiting his neighbors, where he was entertained by the company, showing his poverty, played himself on a defenseless service

In the environment of petty nobility, there were often conflicts between neighbors, and too close proximity, when the "manors" were located next to each other on the same street in the village, often caused random quarrels to turn into fights with the participation of all residents.

It was enough for one noblewoman to notice that her neighbor's cow had entered her garden, and helpers and relatives were immediately summoned to chase or mutilate the uninvited four-legged guest. ... . It happened that hated neighbors were poured with boiling water.

Screams and curses drew onlookers and dogs from all over the neighborhood each time; the peasants, serf rivals, their relatives and residents also appeared in an instant, armed with everything they could get their hands on.

As a result, the clearing where a cow grazed peacefully, which violated the "official" border of the neighboring garden of the property, soon turned into a battlefield there were barking dogs, tavern curses, groans of the wounded and maimed.

Source

The text is an excerpt from the book by Boris Kreshensev, “Captive Russia. A history of serfdom ”, which was published by Wydawnictwo Poznańskie.