44 B.C.E. has pushed the fate of the world on a completely new course. 23 blows inflicted on Caesar by a group of high-born bombers led to the fall of the Roman republic. The system collapsed, the empire arose ... but what about the people who wiped out the most popular politician of this era?

Right after the funeral ceremonies, the Roman masses started looking for murder. First, it attacked the houses belonging to the leaders of the plot - Brutus and Cassius. The attack failed, but another victim was found along the way. Pretty random.

A certain Helwiusz Cynna really found himself in the wrong place and at the worst time. He was taken for consul Cornelius Cynna, who recently took a tough stance against Julius Caesar. He did not have time to explain that his name was Helwius and not Cornelius. “The tin was ripped open in an instant, his head was stuck on the spear's edge and they were carried around the city. "

Professionals had to deal with the liquidation of Caesar's murderers. In 43 BC, a year after the murder, Lex Pedia was adopted . Under this law, all conspirators were sentenced to banishment. The main avengers were played by Octavian Augustus, the adopted son of Caesar, and Mark Antony, a trusted commander and at the same time a distant relative of the murdered. Before that, they were in conflict with each other, but decided to join forces.

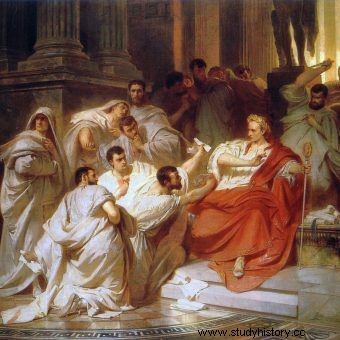

Up to 80 senators could have participated in the conspiracy to kill Caesar. Pictured is a painting by Jean-Léon Gérôme of self-satisfied conspirators (source:public domain).

Of course, it was one thing to pass the relevant resolution in the Roman Senate and another to implement it. About 60 senators participated in the conspiracy to kill Caesar (maybe even 80, if you trust other accounts), as if you were not looking at representatives of the Roman elite, and Julius's death marked the beginning of a civil war. Lex Pedia was a legal weapon in the hands of Octavian and Antony, but in order to enforce its provisions, they had to use a weapon in the literal sense of the word.

Trebonius loses his head

Even before the release of Lex Pedia , in January 43 BC, the first of the conspirators, Gaius Trebonius, lost his life. For many years he served under the command of Caesar, later thanks to him he became a consul, and then became the proconsul of Asia, i.e. the governor of today's western Turkey. Before he left for the provinces, he took part in the murder of a benefactor. When the other conspirators murdered Caesar, Trebonius stopped by talking Mark Antony, who was going to meet Julius. Had he arrived sooner, perhaps the murderers could have been stopped…

In order to bring justice to Caesar's assassins, Mark Antony and Augustus, who had so far quarreled, joined forces (source:public domain).

Then Trebonius left for Asia and locked himself in Smyrna (today's Izmir). One night, the troops of Consul Dolabella, a gloved man, this time acting as a supporter of Mark Antony, stormed the unguarded city.

Trebonius had no time to escape; he was caught in his own bed. He did not resist, said he would go to Dolabella voluntarily. Come on, said one of the centurions, just leave your head here, because we have orders to deliver not you, but your head . And cut off its skull. The next day, the soldiers insulted the body of Trebonius, and threw their heads with laughter over the stone-paved streets with their heads as if they were laughing town until they distorted and smashed it .

A Roman who pretended to be Gala

Eight months later, in September 43 BCE, another killer died - Decimus Junius Brutus, a lesser known relative of Mark, one of the leaders of the plot. On the scale of ingratitude, he definitely trumped Trebonius. Caesar gave him the governorship of Pre-Alpine Gaul, and in his will he included in the group of "reserve" heirs.

Decimus defended himself for a time in Gaul, but was eventually abandoned by his troops and waited for a fall with only 10 comrades. He knew the language of the locals, so he changed into a Galician costume and, pretending to be Gala, thought that he would somehow escape Mark Antony's troops. The plan was partially successful, because it fell into the hands of the Romans, but of a certain Camilus, a leader of a Gallic tribe with whom he had known from years ago.

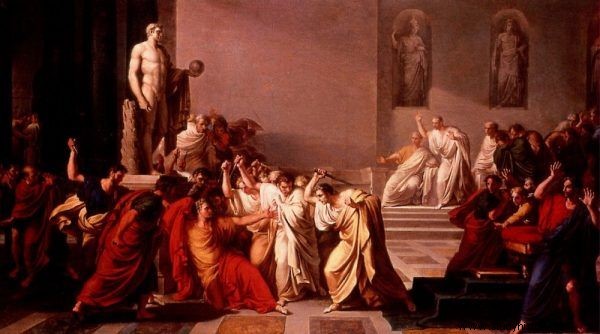

The ungrateful Trebonius paid for his part in Caesar's murder with his head, literally. The illustration shows the death of Caesar by Vincenzo Camuccini (source:public domain).

Camilus welcomed Decimus kindly, but secretly let Antony know what kind of guest he had at his place. The answer was unequivocal:"Send me his head." Shortly thereafter, Decimus's head fell into the hands of Mark Antony. At about the same time, another murderer of Caesar lost his life. Senator Minucius Bazylus was "murdered by his slaves when he condemned several of them to castration."

Main course

If the taste of revenge is compared to eating, then Trebonius, Decimus and Basil were appetizers, and the main course was Gaius Cassius and Marcus Junius Brutus, leaders of the plot to kill Caesar. They both died in the fall of 42 in the battles of Philippi. Antony and Cassius faced the first battle, Octavian and Brutus in the second.

On his way to Philippi, Cassius made a speech as if taken from an epic historical movie.

If any of you used to be Caesar's soldier, don't be scared of it. For we were not serving him then, but his homeland, and the rewards and gifts were not from Caesar, but from the treasury; likewise, now you are not the army of Cassius or Brutus, but rather the Roman people, and we, the Roman leaders, are your comrades-in-arms - encouraged the legionnaires to fight.

Conflicting reports have been made about Cassius' death. One of them says that he mistook the Brutus riders heading towards his tents for enemy soldiers. The mistake had dire consequences. Not wanting to fall into the hands of Octavian and Antony, he ordered his slave to kill himself.

Although the exact circumstances of Cassius' death are unknown, one thing is for sure, he paid the ultimate penalty for planning the murder of Caesar. The illustration shows Cassius' denar (source:cngcoins.com; lic. CC BY-SA 3.0).

After losing the battle, Brutus realized that his men did not want to continue fighting. In this situation he asked his friend named Straton to kill him . While he told him to think again, Brutus called one of the slaves. Then Straton protested: You don't need a slave, to fulfill your last recommendations you cannot lack the services of a friend, if you have already decided to do so . And he plunged the sword into Brutus' side.

Monument for Pontius

Most of Caesar's assassins were punished under Lex Pedia . Among them was Servius Sulpicjusz Galba. It is ironic that the great-grandson and namesake of Galba, who hates so much authority and defends the Republic, became emperor in AD 68.

The fate of Pontius Aquila, probably a relative of the most famous Pontius - Pilate, was exceptional. He was a tribune of the people, and he was the only one among this official who did not rise when Caesar made his triumphal entry into Rome. Julius was resentful and quite often made promises with the ironic stipulation "if I obtain the consent of Pontius Aquila."

Brutus chose death at the hands of his own friend. Pictured is Brutus by Peter Paul Rubens (source:public domain).

Aquila, in the great chaos that reigned in the Roman Republic after Caesar's death, lost his life in the Battle of Mutina in April 43 BC, fighting against Mark Antony under the command of ... Octavian. Only after this battle did the political paths of Antony and Octavian converge. It was fortunate for the family of Poncjusz Aquila that he died just then, and not in another clash. Instead of condemnation and confiscation of property, posthumous glory and financial profits awaited. Octavian had a monument erected for Pontius and his heirs returned the money that the deceased had invested in the fight against Antony.

Cassius Parma is the last to die

None of the murderers survived Caesar for more than three years and died a natural death - wrote the Roman historian Suetonius. - All, convicted by law, lost their lives in various circumstances:some in a shipwreck, some in armed combat, some took their own lives with the same dagger they had struck Caesar.

The information is inaccurate because one of the murderers survived . His name was Cassius Parma, and he had a pretty good fleet. After the battles of Philippi, he established cooperation with Sextus Pompey, the ruler of the pirate state in Sicily. A few years later, the army of Octavian Augustus smashed Pompey's forces, so Cassius Parma had to look for a new ally.

After the battle of Actium, Cassius Parma tried to hide in Egypt, but it did not help much. The picture shows the said battle by Laureys and Castro (source:public domain).

At that time, only two great leaders remained on the Roman political scene - Octavian and Mark Antony. The paths of the recent allies diverged. Cassius Parma did not have much room for maneuver:at one time he wrote a letter accusing Octavian of low origin.

So Cassius Parma allied with Mark Antony. After his defeat at the Battle of Actium in 31 BC, he took refuge in Athens, where he fell into the hands of Octavian's men and was executed.

***

Empire is a six-episode series that takes us back to the times of ancient Rome. The protagonist is the gladiator Tyrannus - Caesar's trusted man, who stands by Octavian's side after his death. The young patrician is only taking his first steps in politics, he also has to face dangerous opponents. The creators of the series go back to the history of the Roman Empire, although the facts and real characters are the starting point for a captivating story about power, politics, and love.

Studies:

- Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology , Vol. 1, ed. William Smith, London 1844.

- Rogosz Norbert, The question of the secret of the conspiracy of M. Junius Brutus and G. Cassius Longinus , "Old and New Ages", vol. 3 (8), 2011, pp. 9-35.

- Rogosz Norbert, The participation and role of Caesarians in the attack on G. Julius Caesar (March 15, 44) , "Old and New Ages", vol. 1 (6), 2009, pp. 39-56.