It was supposed to be a show triumph of the party. With the end of the proceedings, the history of the arduous opposition was also expected to end. The whole thing, however, turned out to be a compromising failure of the rulers. How is it possible that they have failed to win a predetermined trial?

From the moment of the imposition of martial law, the communist authorities were getting ready to organize a famous show trial for the most important activists of the Social Self-Defense Committee "KOR" and the Independent Self-Government Trade Union "Solidarity". There were two main goals with it.

The first was propaganda. The idea was to prove that the leaders of both opposition organizations were responsible for escalating the political conflict - and thus leading to a situation in which it became necessary to introduce martial law. The second goal turned out to be a bit more practical:the leaders of the KSS "KOR" and the NSZZ "Solidarność" were to read the severe prison sentences. In this way, they were to be eliminated from any public activity for a long time.

(….) or the death penalty…

The trial was to cover activists of the KSS "KOR":Jacek Kuroń, Jan Lityński, Adam Michnik, Zbigniew Romaszewski and Henryk Wujc, as well as Jan Józef Lipski and Mirosław Chojecki who were staying abroad. On the other hand, members of the National Commission were qualified to prosecution from "Solidarity":Andrzej Gwiazda, Seweryn Jaworski, Marian Jurczyk, Karol Modzelewski, Grzegorz Palka, Andrzej Rozpłochowski and Jan Rulewski.

One of the defendants in the trial of "eleven" was Jacek Kuroń, co-founder of KOR, after Poland regained freedom, a member of the Sejm of the 1st, 2nd and 3rd term of office. Pictured with the opposition during the May Day demonstration in 1989.

Preparing the trial, the Ministry of the Interior relied on the resolution adopted during the meeting of the presidium of the National Committee of Solidarity on December 3, 1981 in Radom. The opposition leaders proposed in it, inter alia, that the union demanded changes to the electoral law for national councils and the Sejm, calling new elections, taking control of the economy and removing radio and television from the control of the authorities.

On this basis, analysts of the Ministry of Internal Affairs stated in one of the documents that " the leading activists of NSZZ" Solidarność "(...) undertook, in consultation with other persons, activities aimed at overthrowing the system of the Polish People's Republic by force ". However, with such a charge, Article 123 of the Criminal Code was applicable, which read as follows:

Whoever, with the aim of depriving independence, tearing off part of the territory, overthrowing the system by force or weakening the defense power of the Polish People's Republic, undertakes, in consultation with other persons, activities aimed at achieving this goal, shall be punishable by imprisonment for not less than 5 years or by death .

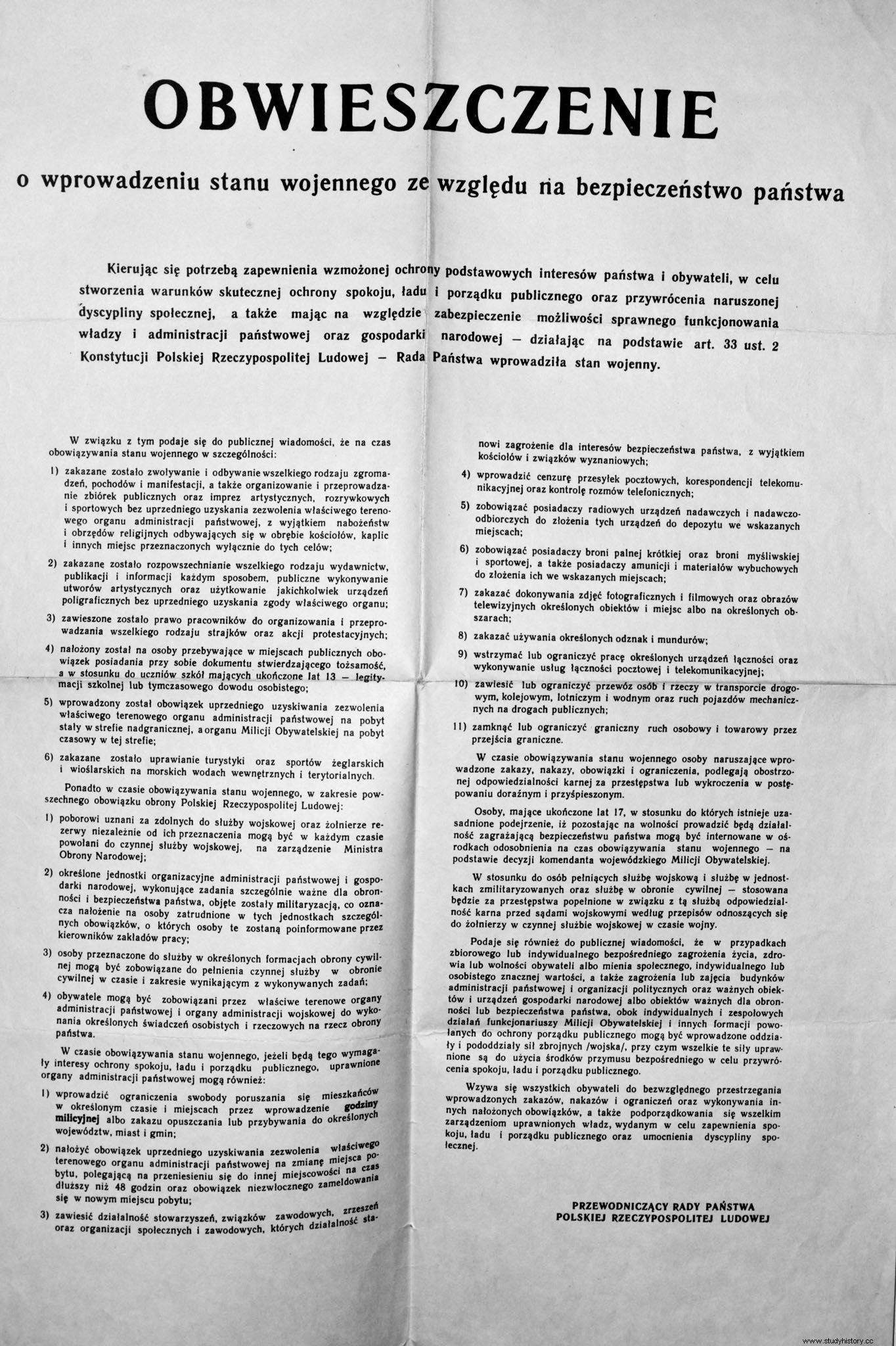

This one announcement, issued by the Council of State, radically changed the situation in Poland overnight. The imposition of martial law meant uncertainty and fear not only for the opposition but also for ordinary citizens.

The biggest and most important

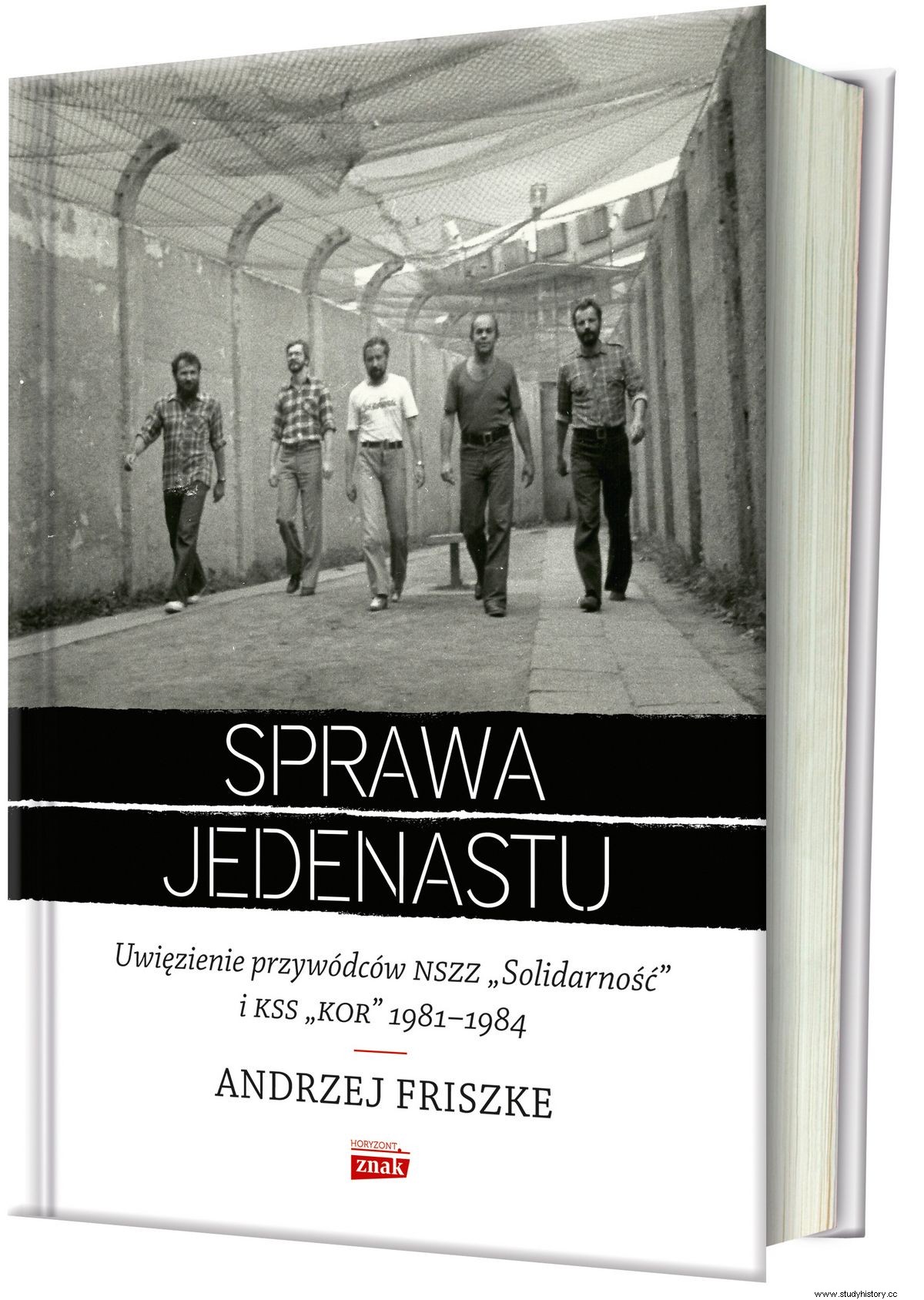

All the above-mentioned opposition activists (with the exception of Jan Józef Lipski and Mirosław Chojecki) were interned on December 13, 1981 or arrested shortly thereafter. Preparations for the show trial ahead of them were extensive. This is what prof. Andrzej Friszke in his latest book entitled The Case of Eleven. The imprisonment of the leaders of NSZZ "Solidarność" and KSS "KOR" 1981-1984:

The investigation against the leaders of Solidarity and the KSS "KOR" was the largest criminal case that the PRL authorities conducted after 1956 . As never before, all departments of the Ministry of the Interior were involved in the case, and for the Investigation Bureau of the Ministry of Internal Affairs it was the most important issue in 1982-1984. The course of the investigation and the specific proposals related to it became the subject of interest and consultation at the highest levels of the party and the state.

The article was inspired by the latest book by prof. Andrzej Friszke “The Case of Eleven. The imprisonment of the leaders of NSZZ "Solidarność" and KSS "KOR" 1981-1984 ″ (Znak Horyzont 2018).

Task ordered by the prime minister

The immediate organizer and coordinator of the project was an experienced officer of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, head of the departmental Bureau of Investigation, Colonel Hipolit Starszak. There was also a special team consisting of representatives of the Administrative Department of the Central Committee of the Polish United Workers' Party, the General Prosecutor's Office and the Supreme Military Prosecutor's Office.

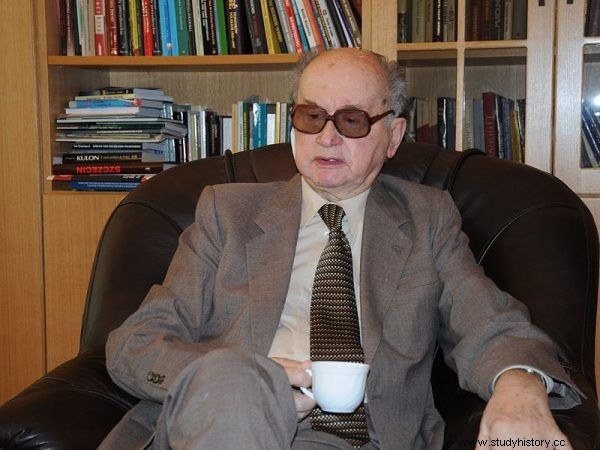

The most important people in the country, including Wojciech Jaruzelski, Stefan Olszowski, Mirosław Milewski, Kazimierz Barcikowski, Florian Siwicki, Mieczysław Rakowski and Czesław Kiszczak, were informed about the preparations. The communist decision-makers wanted to deal with the matter as quickly as possible. Jaruzelski put pressure on it, and his demands were passed on to his subordinates by the head of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, General Czesław Kiszczak, who in one of the letters noted:

Task ordered by the Prime Minister [i.e. Wojciech Jaruzelski, who was then, inter alia, the prime minister of the government - ed. PS] is the trial of Kuroń and his associates for anti-state activities. It must be taken care of by all SB operational units, mainly the Investigation Bureau .

Wojciech Jaruzelski (in the photo from 2009) on the night of December 12/13, 1981, became the head of the Military Council for National Salvation, which exercised actual power in Poland during martial law. And it was him who wanted to sink the opposition as quickly as possible.

Process eleven

The hastily collected evidence (including seized Solidarity documents and data from wiretaps and denunciations) was quickly transferred to the Chief Military Prosecutor's Office, which initiated an investigation on February 1, 1982. Meanwhile, there were discussions between the authorities and institutions involved in the project as to what the indictment and the trial itself should look like. It was discussed how many people should be accused (initially as many as 30 were taken into account), whether to organize one trial or several, whether it should also include activists of the Confederation of Independent Poland, and whether Lech Wałęsa would be one of those who would face charges.

In November 1982, the oppositionists were commuted to arrest. In July 1983, under an amnesty, the majority of those imprisoned during the martial law were released. However, the above-mentioned eleven activists of "Solidarity" and of the KSS "KOR" remained in custody. It was for them that the demonstration trial was to take place.

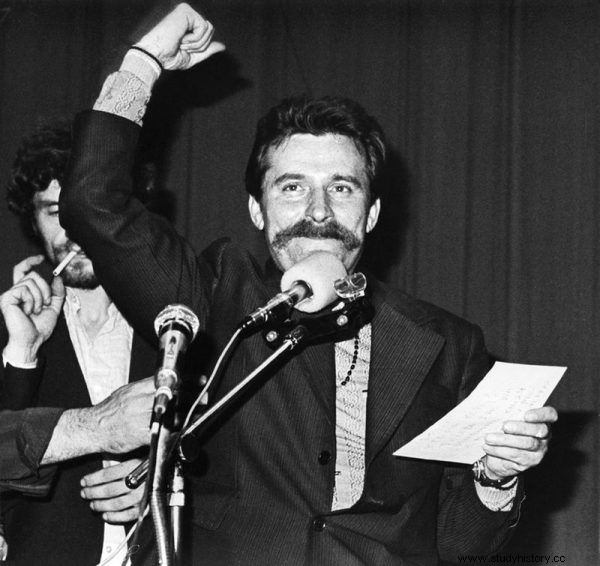

Why did Lech Wałęsa avoid the fate of the famous "eleven" who were indicted in the years 1981-1984? Is it possible that the authorities of the Polish People's Republic wanted to divide the opposition and sow doubts as to the honesty of one of its leaders? The photo shows Wałęsa during the August 1980 strike at the Gdańsk Shipyard.

The defendants did not include Jan Lityński, who did not return from the pass he received in June 1983. He was in hiding and was active in the underground until October 1986. In turn, Jan Józef Lipski, after returning to Poland, was arrested in November 1982, but was released after three months due to poor health. Mirosław Chojecki was still abroad.

I think we're in trouble…

Meanwhile, the trial of the opposition activists, which was being prepared, unexpectedly became a big problem for the authorities of the People's Republic of Poland. The imprisoned were well-known activists enjoying authority in society, and the news of their imprisonment reached the West and sparked protests there.

Former members of the KSS "KOR" (the Committee was dissolved in 1981) acted to publicize the situation of the detained, including:Anka Kowalska, Halina Mikołajska, Ewa Milewicz, Antoni Pajdak, Aniela Steinsbergowa and Fr. Jan Zieja. Letters and petitions to the rulers (also abroad) were written in defense of those arrested. One of them was signed by such personalities as:Andrzej Wajda, Andrzej Kijowski, Halina Mikołajska, Marian Brandys, Julian Stryjkowski and Stefan Kieniewicz.

On the matter of detainees in the United States, the then national security adviser to the President of the USA, Zbigniew Brzeziński, spoke, and Polish bishops intervened in the country. Articles devoted to the arrested activists appeared in the foreign press.

As reported in his latest book, The Case of Eleven. The imprisonment of the leaders of NSZZ "Solidarność" and KSS "KOR" 1981-1984 prof. Friszke, in November 1982, Niall MacDermot, the secretary general of the International Commission of Lawyers, appeared at the Permanent Representation of the People's Republic of Poland to the UN Office in Geneva. Referring to article 14 of the International Covenant on Civil Rights, he asked whether the authorities of the People's Republic of Poland would agree to attend the hearing by a member of the Commission who would act as an observer. The rest of the world did not intend to turn a blind eye to the show trial .

Kiszczak says:emigration

The case became so loud and the pressure so strong that the authorities began to look for a compromise solution to the embarrassing situation. In July 1983, amnesty was announced. However, it did not include the famous "eleven". Instead, the authorities made her a clever offer: offered to emigrate with the right to return only after about five years ...

One of the closest associates of General Jaruzelski was Czesław Kiszczak - a member of WRON and co-organizer of martial law in Poland. In the photo Kiszczak with Eric Honecker (right), the then leader of the GDR, in 1988.

Such a trick would solve the problem of an uncomfortable trial and - and that would be the main benefit - it would remove the leading and most active oppositionists from the country. The author of the idea was General Czesław Kiszczak, and it was mentioned semi-officially - at one of his famous press conferences - by the government spokesman, Jerzy Urban. Some of those arrested in advance rejected the offer (including Jacek Kuroń, Adam Michnik and Karol Modzelewski), others were willing to seriously consider it.

Michnik writes to Kiszczak

The issue was finally decided by an emotional letter written by Adam Michnik to the head of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, General Czesław Kiszczak, in which the opposition scornfully rejected the proposal to emigrate, which in his opinion was unworthy. In it he wrote:

You admit that the aim of the pending criminal proceedings is not to redress the law, but to get rid of the troublesome opponents by the elite (...). To openly admit to trampling the law, you have to be a fool .

Michnik's resolute attitude strengthened the resistance of the other prisoners. Nobody decided to emigrate.

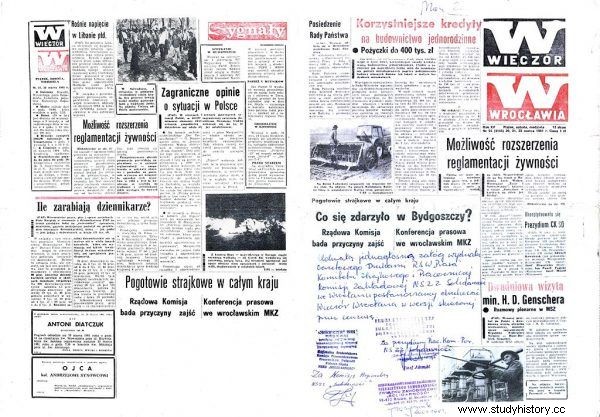

While opposition leaders were held in custody, trade unionists were not only harassed but also beaten. The illustration shows a copy of the daily "Wroclaw Evening" from March '81 with censorship interventions in the text commenting on one of such incidents.

Another attempt to solve the problem was Primate Józef Glemp's proposal that the prisoners be subject to the 1983 amnesty in exchange for their promise to cease public activity by 1986. The authorities were willing to agree to such a deal (in fact beneficial to them); he was also unofficially backed by the Temporary Coordination Committee of NSZZ "Solidarność". Most of the detainees, however, rejected the idea of the Polish Church.

In order to force the authorities to start the trial (the oppositionists have already been imprisoned for 2.5 years!), Jacek Kuroń started a hunger strike in June 1984 . The American State Department stood up for the prisoners. Amnesty International also got interested in the case. The trial finally began on July 13, 1984, and the defendants displayed a tough and arrogant attitude during the trial (especially Adam Michnik). Western media reported extensively about the trial, and the French 'Le Matin' titled its report 'The Stalinist Trial in Warsaw'. Pope John Paul II prayed for the prisoners.

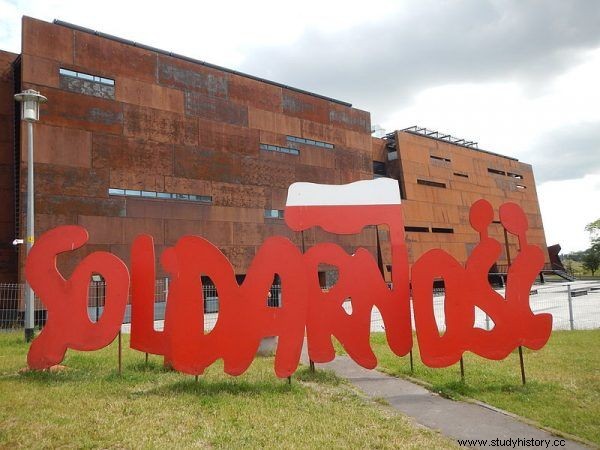

Although the establishment of the leaders of NSZZ "Solidarność" and the KSS "KOR" was intended to discredit the opposition by the authorities of the People's Republic of Poland, it had different results. Was this show trial one of the elements that led to the overthrow of the regime? The photo shows an art installation in Gdańsk.

Very short process

The trial was stopped after the second court hearing. Feverish consultations on how to get out of an awkward and loss-making situation continued at the top of the government. Finally, it was decided to take a radical step:on July 26, 1984, the case was discontinued under the amnesty announced in connection with the 40th anniversary of the establishment of the People's Republic of Poland this year. Eleven opposition activists were fired in turn. Prof. Andrzej Friszke in the book The Case of Eleven. The imprisonment of the leaders of NSZZ "Solidarność" and KSS "KOR" 1981-1984 this is how the famous process summed up:

The fact that the regime eventually went back and the processes did not take place was the result (...) the steadfastness of the arrested leaders who did not bow to violence, did not allow themselves to be divided or intimidated, did not cooperate with investigators, showed readiness to resist. The authorities had to reckon with the fact that the trial would be a difficult experience for them, and the accused would turn into accusers of the regime. The goals set at the beginning - to overthrow the legend of Solidarity and its leaders - were not achieved, and full control over what was happening in the courtroom turned out to be impossible .