People dying in terrible torments. Babies pierced alive and thrown into fire. Women who are defenseless and exposed to the lust of the soldiers. We present the most disgusting examples of Moscow brutality in the occupied country.

The outbreak of the Kościuszko Uprising in 1794 was a surprise for Russia. It seemed that the truncated Commonwealth - for years treated by St. Petersburg as a protectorate - lacked the inner strength to oppose foreign domination in any way. Meanwhile, it unexpectedly turned out that the hull Poland had met with extremely strong resistance and threatened to throw off the Russian sovereignty. So it was decided to quell the rebellion quickly and without any sign of pity .

Dreadful fields

The Russians were in a good position. Their numerous troops occupied the Republic of Poland. In Poland (in the Crown and in Lithuania) as many as 30,000 Russian soldiers commanded by the Moscow envoy in Warsaw, Osip Igelström, were stationed. The Russian army, who stayed in the Republic of Poland for years, felt at home here.

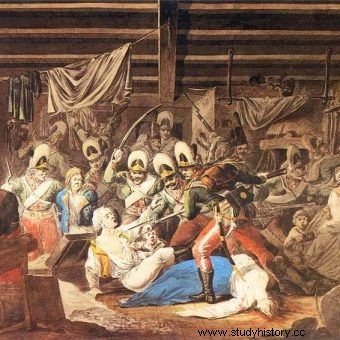

The slaughter of Praga in the painting by Aleksander Orłowski from 1810.

This is what the historian of national uprisings and military, Wacław Tokarz wrote about it:

This military took wages, food and feed from its treasury, as well as lodging, feed and digestible from the country. Every non-commissioned officer here was the lord of the village where he stood in his quarters; each officer made a fortune, robbing in addition his own treasure through the retention of series receivables and false daily records of his department's status.

The outbreak of the uprising took the Russians by surprise. The painting by Franciszek Smuglewicz from 1797 shows the Kosciuszko oath on the Main Market Square in Kraków, which marked the beginning of the insurrection.

Thus, the Commonwealth bore the costs of maintaining the tsarist troops that occupied it (and robbed it).

Looting the living and the dead

The route of the Moscow troops during the uprising was marked by requisitions, fires, robberies and rapes. For example, the unit of General Khrushchev, sent back to Russia with prisoners and loot, had no qualms about plundering mansions, palaces and bourgeois houses, and even country cottages along the way.

It was common to steal from Polish soldiers who died in combat and from prisoners taken prisoner of war.

Writer, historian and diarist Julian Ursyn Niemcewicz, who watched one of the battlefields, noted that all the bodies of the fallen Poles were stripped almost naked.

The shocking practice is described by Piotr Śliwiński in his latest novel entitled Ryngraf :

Cossacks led the way in robbing the corpses, although soldiers of other formations were not idle, committing blatant rape and blows on the prisoners, just to get a signet ring, a ring or a cross noticed on their fingers on the chest. There were also officers among the robbers.

Injured POWs without care

The Russians not only turned out to be cemetery hyenas, but also showed their absolute contempt for human life. When they defeated the forces of the insurrection in the decisive battle of Maciejowice , severely wounded Tadeusz Kościuszko was taken prisoner, but left the masses of soldiers for certain death.

"Kościuszko is wounded in the Battle of Maciejowice". Painting by Jan Bogumił Plersch.

Nobody looked after the Poles and nobody looked after them. The night has come, broken by the groans of the wounded and dying soldiers the 10th regiment and the battalion of fusiliers lying in the castle cellars. They were soldiers who, after the defeat of the right wing, retreated to the castle and here defended themselves to death against the overwhelming opponent, who fiercely stormed the building. Of course, those who were dying in terrible suffering, from wounds inflicted with bayonets, were not helped by anyone. They were left to their own fate - we read in the monograph of the Battle of Maciejowice.

Moscow Killing Frenzy

The greatest crime committed by the Russians during the Kościuszko Uprising was undoubtedly the slaughter of Prague . On November 4, 1794, 23,000 Russian forces struck the right bank of Warsaw, defended by 13,000 soldiers of the Lithuanian army:poorly trained and equipped, and in addition demoralized by the constant retreat from Lithuania.

The Russians quickly broke the insurgent fortifications and crushed most of the Polish troops. Then they proceeded to brutally murder prisoners of war and local civilians.

There were many bodies left on the battlefield, and there was no one to treat the wounded. Painting by Aleksander Orłowski "Battle of the Kościuszko Army with the Russian for a river crossing".

Almost all the nuns were raped and murdered in the Bernardine convent. In the Bernardine monastery 19 monks and seven crippled old men living in the local shelter were killed. People were dragged out of their houses onto the streets to be tormented in public - mutilated and finally killed.

Women with children were murdered. Cossacks torn babies from their mothers and put them on lists or threw them into the fire. In a beastly frenzy, the Russians did not even spare animals, killing horses, cats and dogs ...

They must all die!

The German writer Johann Seume, then serving as an officer in the tsarist army, recorded the following story:

Colonel Lieven, who commanded the regiment during the assault, and later was the commander of the square in Praga for some time, replied that he himself encountered a grenadier at the end of the battle. he had a rifle in his left hand and every Pole without exception was hoping for a bayonet , he did not even let the seriously wounded pass, and with the ax he had in his right hand, he smashed their heads with a blow of grace.

The horrors of the Praga massacre on a 19th-century woodcut based on a painting by Juliusz Kossak.

The colonel condemned his inhumanity and told him that he could kill armed but not wounded and poor defenseless. "Eh, sir," he replied furiously, "they're all dogs, they fought against us and must die" .

In turn, a Prussian food commissioner wrote:

The view of Prague was terrible, people of both sexes, old men and babies at their mothers' breasts were lying in a pile; blood-stained and exposed bodies of soldiers, broken carts, slaughtered horses, dogs, cats, even pigs. Here and there the members of the dying still trembled. The whole city of Prague was in flames and smoke, and the rooftops collapsed with a crash matched by the terrible howl of the Cossacks, the curse of the furious soldiers. The blood-soaked corpses of the victors were strewn with their purchases (...)

Nobody has dared to show themselves in Praga so far; a few Jews, greedy for profit, arrived, but those Cossacks immediately seized them by the feet, and beat their heads against the wall until the brain spurted out, and then they divided the found money among themselves .

The shocking slaughter lasted several hours. The number of murdered people is difficult to determine. It is estimated that from several thousand to even 20 thousand people died .

On foot to Siberia

The fate of captured prisoners of war can be considered the last installment of the Russian crimes during the Kościuszko Uprising. Some of them were forcibly drafted into the Russian army, while the rest were driven deep into the empire on foot. The number of exiles is not certain. However, it is said that the number ranges from 5-6 to about 20,000 internees.

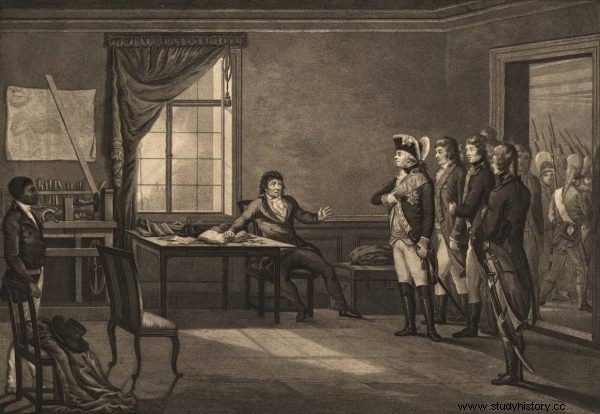

The final chapter of the insurrection took place deep in Siberia. The Chief himself came a bit closer - to the St. Petersburg Fortress of Peter and Paul. In this engraving, based on a painting by Aleksander Orłowski, Tsar Paweł I visits Tadeusz Kościuszko.

In the territories incorporated into Russia as a result of the second partition of Poland, an investigation was carried out against the participants of the uprising. They were conducted by a special commission. In July 1795, it issued a number of sentences, dividing the convicts into 11 categories depending on the degree of guilt. Those in categories 1 and 2 were sentenced to exile to the farthest corners of Siberia.

Kościuszko himself ended up in St. Petersburg, where he was held in the Peter and Paul Fortress. The Poles exiled and imprisoned in Russia were given the opportunity to return to the country under the amnesty announced by the new Tsar Paul I on December 10, 1796. Of course, only those who survived the harsh Siberian conditions could return ...