An uninterrupted barrage of fire, masses of cavalry and crowded soldiers, marching under enemy volleys. Almost eighty thousand massacred soldiers. And a commander who ignores all appeals for help. In a word:a battle after which the history of wars was never the same again.

“The Borodino Slaughter had long held a gloomy record as" the bloodiest battle since the invention of gunpowder. " A real shock, a harbinger of mass massacres during the Civil War, and later during the clashes of World War I, those steel storms during which the man of the 20th century was reduced to the role of material - like lead or gunpowder put at the disposal of the general staff to ensure victory for him " .

This is how Sylvain Tesson writes about the battle of Borodino:author of the book Berezina. About male friendship, motorcycle journeys and the Napoleon myth . So what was the clash that changed the history of wars like? And was it really that devastating?

Signal to attack

The vicinity of the village of Borodino, about 130 kilometers west of Moscow, seemed to be the last place to stop Little Corporal on his way to Moscow. The commander of the Russian army, General Kutuzov, ordered huge fortifications to be erected here. The most important of them were the Great Redoubt (also known as Rajewski's redoubt), the Bagration redoubt and the three arrows redoubt.

Commander-in-chief of the Russian troops, General Mikhail Kutuzov.

At Borodino, the Russians had considerable strength. Despite the losses in combat and due to disease and desertion, about 130,000 regular troops, Cossacks and the surrounding area (the Moscow mass movement) could take part in a general battle. In addition, Kutuzov had significant artillery in the number of 640 guns. Each soldier was also counted on the side of the Grand Army. After the units arriving at Borodino were joined, just before the battle, the state of the Grand Army reached approximately 126,000 soldiers with 587 cannons.

Before dawn on September 7, 1812, Napoleon went to the battle post shouting the famous words:"Behold the sun from Austerlitz!" . However, he did not have a dazzling victory like that of 1805. It was supposed to be the second Wagram (1809):a battle without unnecessary maneuvering, changing fronts and surprising the enemy. Tired and sick, Napoleon was getting ready for a brutal fight to exhaustion.

According to the assumptions, the signal for the attack was to be the attack on the right wing of the V Corps of Prince Józef Poniatowski. Indeed, before 5 a.m., Polish troops began to move along the old Moscow route. Soon they also came into combat contact with Russian Jegers. Limited space and field difficulties, however, meant that the prince's forces were stopped quite quickly.

Shots coming from the south convinced Napoleon that the Poles had already moved to the Russian left wing. So the remaining corps began the fight. After 6 o'clock the French battery guns roared. The entire line of Napoleonic troops immediately launched an attack.

Surprise attack

The soldiers of the left wing commanded by the viceroy of Italy, Prince Eugene de Beauharnais, entered the fight first. At around 6.30 am, they hit the fortified village of Borodino. The infantry of the Italian corps, taking advantage of the morning fog and complete surprise, took the village, the bridge over Kołoczy, and attacked the village of Gorki, further to the east. The Russians recovered after the first shock and with murderous cannon fire they began to sweep away entire ranks of Napoleon's foot soldiers. At the same time, there was a counterattack by infantry that pushed Prince Eugene's soldiers towards the river. They managed to retreat to Borodin relatively efficiently and did not allow their conquest to be taken away.

Mastering the position of Borodin was Napoleon's success. Gaining a position on Kołoczą itself involved considerable Russian forces that could not be used in another section. Prince Eugene treated this task in the same way. His artillery started a duel with the Russian cannons standing near Gorki. Part of the fire was also directed at the Great Redoubt, which has now become the main target of the attack by Prince de Beauharnais. For this reason, most of the forces of the Italian Viceroy shifted to the right, opposite the redoubt and Rajewski's corps.

The signal for the attack was to be given by the Polish prince Józef Poniatowski (in the painting by Juliusz Kossak).

Immediately on this episode, the Moranda division entered the fray. However, her movement was slowed down by inconvenient terrain. The Russians began to load their 200 guns with cannons, which were tearing bloody holes in the French ranks. About 30 paces in front of the embankment crown, the French stopped, fired a volley and launched an attack on bayonets. The Russians fought extremely bravely on that day. However, this was not enough in the face of the fury of the French attack.

The soldiers of the Great Army captured the Great Redoubt. At this, however, the impetus of the Napoleonic attack was exhausted. Morand's torn troops stopped because they were not supported in time by further divisions. So the attack stalled in this episode.

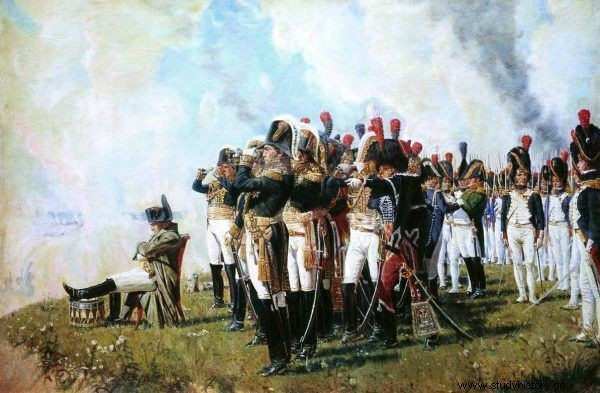

"Napoleon at Borodino" by Vasily Verschhagin from 1897.

The units of the center also went in motion almost simultaneously. The divisions struggled through the forest thicket. Immediately after emerging from behind the tree line, Napoleon's soldiers were greeted by an artillery barrage from General Bagration's ramparts. The footmen ran in tight ranks, not firing any shots, in order to hunt down the enemy cannons as soon as possible. However, when the entrenchment was literally at hand, General Compans at the head of one of the divisions fell as a result of his wound.

The soldiers hesitated and, in bewilderment, stopped at the murderous fire of the Russian cannons. To save the situation, General Dessaix spontaneously took command of both divisions. At that time, Marshal Davout, who came to the aid of Compans' troops and took over the Russian batteries, was wounded.

Disturbing news

Despite bloody advances along almost the entire line, Napoleon began to receive alarming news that the enemy was not easily yielding. What's worse - around 11 o'clock, the Russian commander-in-chief, General Kutuzov, ordered a counterattack. On the left wing, the Cossacks of Platowa and the cavalry regiments of Uwarow moved to the positions of Prince Eugene. The Italian Corps had to defend itself fiercely in Borodin.

At the same time, General Dochturov's division regained the Great Redoubt. In turn, the reserve Russian regiments came to the aid of Bagration and recaptured the recently lost entrenchments in a bloody battle. In the vicinity of the redoubt, three arrows manned by the corps of Marshals Ney and Davout held their positions with difficulty.

The attack of the French on the Great Redoubt in a painting by Julien Le Blant from 1831.

It all did not bode well for me. At least on the left wing, the troops of Prince Eugene took control of the situation and threw the Platov and Uwarow cavalry to the east with a decisive blow. In turn, in the southern section, Prince Poniatowski slowly, in heavy fights, moved his troops slowly along the forest track towards the village of Utica.

At the same time, when the Poles were taking the Russian positions in the Utica forest, the final conquest of Bagration's ramparts took place. Ney's, Davout's, and Murat's corps launched a violent attack. The attack was with a bang of 700 guns (400 Napoleonic and 300 Russian). The Russian resistance was extremely fierce. However, under the terrible pressure of the crowded masses of people and mounts, the Russian ranks staggered and then began to retreat. Bagration was badly wounded in these fights.

So around noon, the troops of Ney, Murat, and Davout stood in front of the mutilated flank of the Russian army. Behind the hastily formed new line, the marshals saw enemy regiments, their rear devoid of any cover, and even a path for a possible retreat. However, they were too weak to collapse into the center of Russian groups. In this situation, they unanimously demanded the help of the guards. Napoleon, however, refused.

Injured Bagration near Borodino in the painting by Peter von Hess.

At the same time, fierce fighting continued in the Great Redoubt. The fortifications changed hands many times. The marshals and here urged Napoleon to use the guard regiments. However, that day the emperor was implacable on this point. Finally, after half an hour of artillery preparation, it was time for a general assault.

Decisive attack

First, before 15, Murat's cavalry forces struck. The rampart was attacked by 2 cuirassier divisions and light cavalry squadrons. After a short but fierce fight, the cuirassiers, entering the fortifications from the right, stormed into the rampart. The Russian foot soldiers initially relented. However, they quickly recovered and took their fresh prey from the French cuirassiers. Immediately, however, a new wave of Grand Army cavalry rained down on the Russians.

The charge of Murat's troops managed to take the Great Redoubt from the Russians, but to maintain it, infantry was needed as soon as possible. Meanwhile, the impetus of the French cavalry began to weaken against the advancing cavalry from all sides. The tsarist artillery concentrated its fire on the ranks of the powerful cuirassiers. The fire barrage had the desired effect and so far Murat's victorious ride had to protect itself behind the ramparts of Rajewski's redoubt. Then, finally, units of foot divisions arrived at the rampart in a hurried march under cannon fire. Immediately behind them, the cannons were pulled up, which almost immediately started firing the masses of Kutuzov's soldiers swarming behind the fortifications.

Journey in the footsteps of Napoleon's Great Army. We recommend a book by Sylvain Tesson entitled “Berezina. About male friendship, motorcycle journeys and the myth of Napoleon "(Published by Noir sur Blanc 2017).

The final seizure of Rajewski's redoubt after 3 p.m., of course, did not mean the end of the fighting in this section. The fear moved further east. However, the forces of the Grand Army were already exhausted. Murat again called on the emperor to send the Guard regiments into battle.

Probably right after conquering the Great Redoubt, the emperor was willing to send a guard that would complete the measure of destruction of the retreating enemy. However, when news reached him about the creation of a new line of defense by Kutuzov's troops, he hesitated and only ordered the Legia Nadwislanska move to the Great Redoubt and its foreground.

The emperor confirmed his fears by personally examining Rajewski's redoubt around 5 p.m. Bonaparte saw that the enemy had indeed managed to collect his bodies, shaken up by the battle. The new front of the Russian positions was heavily saturated with guns (about 200 barrels). Thus, another attack by Napoleonic troops would cause terrible losses again. In this situation, both fighting sides collapsed in their positions, limiting themselves only to the cannonade of artillery. The battle in this episode seemed to be dying out.

The attack of the French on Rajewski's redoubt in the painting by Louis-François Lejeune.

Meanwhile, in the south, between 3 p.m. and 4 p.m., the corps of Fr. Poniatowski launched his final attack. As a result of an hour-long fight, the Russian forces were rejected for Utica. The army of the V Corps quickly prepared the acquired position for defense. The artillery was set in such a way that it could hit both the path of a possible hit by the enemy, as well as the left wing of the Russian defense in the central part of the fight. The tsarist troops, however, did not take any action here, and the falling dusk, the fatigue of the fight and the lack of reserve also prevented the Napoleonic side from continuing any offensive actions.

At about 10 p.m. Murat appeared in Napoleon's quarters again with a further appeal for the use of the guard, or at least its horse regiments. Napoleon firmly refused this time as well, thus ending the slaughter in the Borodin fields without giving the final blow to the opponent. Even without that, the losses on both sides were enormous.

Balance of the fight

Bonaparte consoled himself by the fact that many more Russians died than his soldiers. Kutuzov's army lost, according to various estimates, from 50,000 to 58,000 soldiers. Of that number, only a few thousand were lost, which meant that the regular Russian army was seriously weakened. The Napoleonic side lost about 30,000 people.

Thus, the battle of Borodino could long be considered the bloodiest battle since the invention of gunpowder. The initial similar balance of power on both sides turned into a decisive advantage of the French emperor's troops. It still had nearly 100,000 soldiers under its command, including the practically intact guard.

Almost 100,000 soldiers died on the battlefield. The picture shows the last pastoral service for Russian soldiers on a battlefield

Soon it turned out how apt was Napoleon's decision not to throw this formation into battle, which as "the last dry cartridge in the imperial pouch" allowed the remnants of the Grand Army to survive the terrible days of retreat and the tragic crossing of the Berezina.

As for the battle of Borodino itself, Sylvain Tesson rightly writes on the pages of the book Berezina. About male friendship, motorcycle journeys and the Napoleon myth :“From Borodino, our era has entered the age of the Titans. From that date on, the war will no longer be limited to a series of skirmishes. It will require the sacrifice of the masses. ”

Selected bibliography:

- Askenazy S., Napoleon and Poland , Warsaw 1994.

- Bielecki R., Great Army , Warsaw 1995.

- Bielecki R, Encyclopedia of Napoleonic Wars , Warsaw 2001.

- Brandt H., Diaries of a Polish officer (1808-1812 ), part III, Warsaw 1904.

- Brandys M., Kozietulski and others , Warsaw 1997.

- Chłapowski D., Memoirs. Napoleonic Wars , Poznań 1899.

- Dróżdż P., Borodino 1812 , Warsaw 2003.

- Golitsyn M., La bataille de Borodino , St. Petersbourg 1840, pp. 51 ff.

- Kukiel M., The War of 1812 , vol. I, Krakow 1937.

- Otieczestwiennaja war 1812 goda , St. Petersburg 1900-1914, vol. XVI, no. 76.

- Ségur Ph., The Diaries of Adjutant Napoleon , Warsaw 1967.

- Tarle E., Napoleon , Krakow 1991

- Toll K., Description de la bataille de Borodino , S. Petersbourg 1839