At first no one even believed this condition existed. Soldiers who complained about it were considered cowards and simulants. They could count on little better treatment than deserters. However, the number of patients grew rapidly and the facts could no longer be ignored.

World War I was nothing like the previous conflicts. In the years 1914-1918, the soldiers had to face great intensity of fighting and a huge amount of sophisticated combat means. The likelihood of injury or death was as high as never before. Murderous artillery fire, machine guns, asphyxiating gases, barbed wire, repeated and unsuccessful attacks - all this took hundreds of thousands of lives. And in those who survived, it induced a paralyzing fear that first overwhelmed and then pushed them into a deep, debilitating depression.

This phenomenon has been known for centuries, but only during the Great War did the frontline trauma affect the fighters on such a scale and to such an extent. Even hundreds of thousands of fighters struggled with mental disorders caused by the difficult conditions of fighting and living at the front.

A fire that drives you crazy

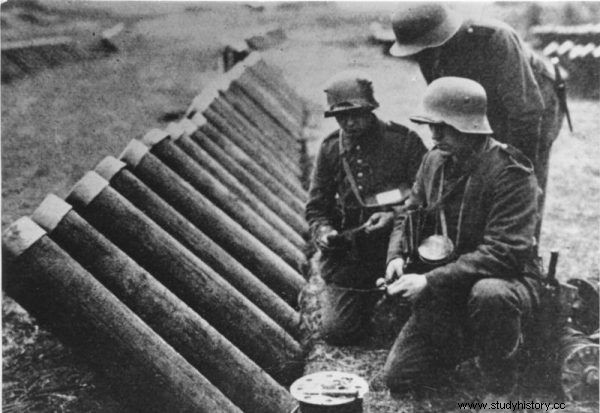

From the memories of the participants of the war it is clear that the most common cause of the so-called frontal neurosis there was a hurricane artillery fire. Fire attacks before the attack became the standard and could last from several hours to several days without interruption, as in June 1916 on the Somme. The British then fired 1.5 million shells from 1.5 thousand guns in five days.

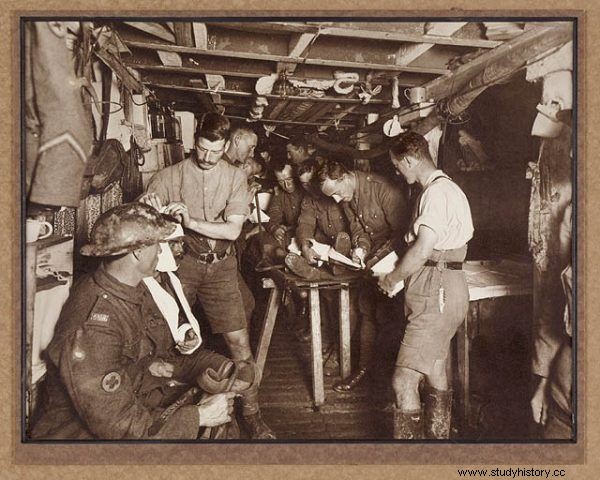

In the years 1914-1918, the soldiers had to face great intensity of fighting and a huge amount of sophisticated combat means. The photo shows the 1st Battalion of the Honorary Rifle Company at Ypres, 1915.

The effect of such gunfire was truly devastating for the human psyche. This is how the French World War I veteran Gabriel Chevallier described it in his autobiographical book "Fear":

The smallest assault is preceded by bombardment aimed at sweeping enemy positions off the face of the ground and decimating and demoralizing their defenders. Those who are spared begin to lose their minds. Nothing I know has such a devastating effect on the morale of the soldiers in the depths of the shelter. The price they pay for their safety is their nerves, ruined and shattered to an unimaginable degree.

The cause of the disturbances could also be other dramatic experiences, such as a serious wound, injury, seeing the death of comrades in arms, covering with soil. Sometimes months spent in the muddy and damp trenches were just enough. The soldiers subjected to such tests did not endure mentally. Overcome with terrible fear, they fell into madness, anxiety, extreme nervousness, even aggression or, on the contrary - into dementia.

They were starting to act weird. They had nervous tics, suffered from insomnia, or had nightmares. Their head ached constantly. Some people lost control of their bladder and intestines. Sometimes these symptoms were accompanied by amnesia. "Soldiers become as weak as children, cry and wave their arms, cling to the nearest neighborhood," wrote a paramedic. One of the British officers recalled the meeting with two subordinates in a state of shock after the shelling:

One of them greeted me like a friend and asked me to give him his baby. I picked up the helmet from the ground and handed it to him. He started rocking him like a baby, taking care of nothing.

Soldiers with symptoms of neurosis were also sent to field hospitals.

In turn, nurse Henrietta Hall of the Bradford Military Hospital wrote in her diary:“They were shaking terribly, which affected their speech. They stuttered terribly and had strange ideas that could only be qualified as hallucinations. They saw things that didn't exist. ”

Cowards and traitors?

The trauma led many soldiers to attempt suicide. Meanwhile, the command, at first disregarding the spreading disease, considered them ... simulators and roofers flashing from participation in the fight. In extreme cases, they were considered cowards and traitors. It even happened that those who were unable to return to the trenches were shot.

However, the number of patients continued to grow. At the end of 1914, about 10 percent of the officers and 3-4 percent of the rest of the British Army showed signs of nervous shock. In 1917, it was almost a quarter of the fighting, and in the second half of 1918 - as many as 80,000 soldiers! Watching them, the military doctors finally decided that they were not fools after all, but actually people with mental health problems. In need of help.

Soldiers showing signs of neurosis were initially often thought of as cowards and simulants.

From a medical point of view, the breakthrough year was 1915. At that time, an article by the psychiatrist Charles Myers was published in the British medical journal Lancet. It was the first time he used the term "shell shock" to refer to soldiers who showed mental problems after heavy artillery fire. Then other names appeared:"trench neurosis", "war neurosis" and "nervose de guerre" (war neurosis), and even "hypnose de batailles" (battle hypnosis). Also distinguished "barbed wire disease" manifested by paralysis before exiting the trenches and attacking by barbed wires.

Dr. Myers began to convince the military that soldiers with neurosis should be treated, not imprisoned or even shot. He did not immediately meet with understanding. Eventually, however, under the influence of his suggestions to fight the symptoms of the disease, they began to evacuate from the front line and directed to a few days' rest at nearby medical points.

Healed after one session

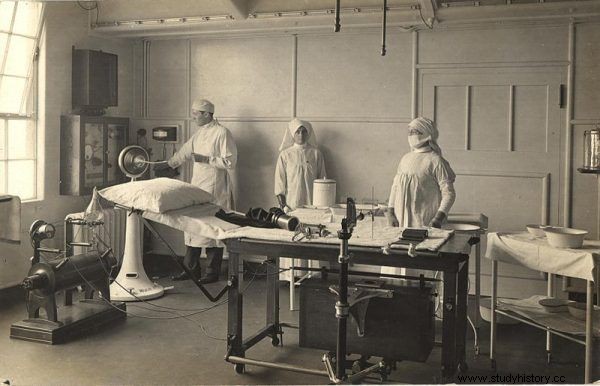

After such "treatment", those less injured were willingly sent back to the front. Only when the condition of the patients remained unchanged, were they sent to one of the four psychiatric centers. The most severe cases were directed to Great Britain, where more complex therapy was attempted in specialized hospitals. The island school for the treatment of frontal neurosis predominantly envisaged individual psychotherapy, involving conversations with the patient, persuasion and suggestion. In cases of amnesic soldiers, hypnosis was also used to restore memories.

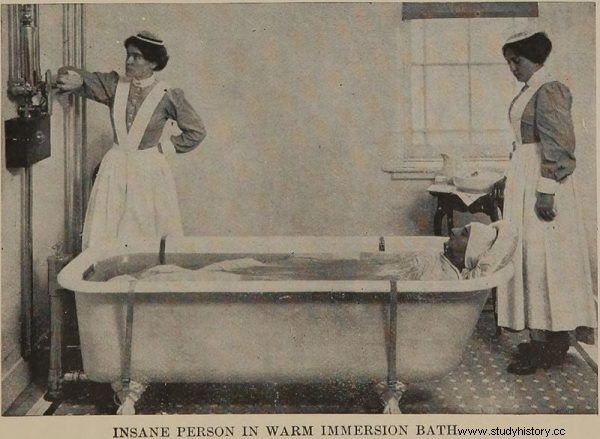

Work on the patient's psyche was supplemented with physical therapy, i.e. (fortunately mild) electrical stimulation, relaxation baths and massage. In convalescence, it was also important to find the patient an appropriate activity that could absorb him. If, despite these efforts, the soldier was unfit for further military service, attempts were made to find suitable civilian employment for him.

One of the elements of therapy for patients with frontal neurosis were relaxation baths. Photo from 1915.

Unfortunately, the new field of research also attracted doctors with dubious qualifications, such as a neurologist, Major Arthur Hurst. He claimed that he could eliminate neurosis in one session. In order to achieve his goal, he used, among others, hyposis and faradization, i.e. low-frequency electric shock. He also recommended that the patients rest. On the other hand, he considered creating an appropriate atmosphere for the soldier's recovery to be the most important. In practice, this consisted in ... the whole therapeutic team having put a strong suggestion on the patient that he would recover quickly.

Some Hurst methods can be considered innovative. He was one of the first to film, for example, soldiers suffering from movement disorders, both at the beginning and during occupational therapy. He wanted to use the tapes later as illustrative material. It looked good until it turned out that some of the pre-treatment shots were actually re-enacted for a movie!

Not only this aspect of miraculous treatment, issued by an ingenious "specialist", raised reservations. The major admitted openly that he used fraud as a therapeutic measure. He was just telling the sick that they would be cured quickly…

Discipline, Discomfort and Electricity

While British methods of combating frontline neurosis may be worrying, among other nations things did not look any better. The French, for example, assessed the whole phenomenon quite differently. Neurologist Georges Guillain wrote in 1915 that "these diseases are completely treatable at first, but patients cannot be evacuated beyond the front lines , they should stay in a military zone.

For the commanders from the Seine, the atmosphere in the therapeutic units was most important. They made sure that they were under military discipline. The sick were deprived of any additional comforts and were in close proximity to military operations . They were also cut off from contacts with their loved ones. In addition, psychotherapy and faradization of the body parts affected by neurosis, such as trembling hands, were used.

In many cases, low-frequency electric shocks were part of the treatment of soldiers suffering from neurosis.

It is hard to believe that these rather specific and not very empathetic methods bring results. Meanwhile, the doctor André Léri claimed in December 1916 that he managed to heal as many as 91 percent of patients! Over 600 of them "recovered" after just a few days of "therapy". Of course, the cured were quickly sent to the front. In total, Léri "recovered" 3,000 soldiers in 12 months.

The sick on the other side of the front were similar, if not worse. German psychiatrists were as tough as their French colleagues. They concluded that neuroses appeared in hysterical individuals, characterized by cowardice, mental instability, selfishness and antisocial behavior.

Kaufmann's method

However, the growing number of cases of war neurosis in the German army made it necessary to pay attention to the problem. During the first year of the war alone, as many as 111,000 soldiers with symptoms of mental disorders passed through military hospitals. Finally, special departments were opened at the university clinics in Berlin, Munich, Heidelberg and Giessen.

The goal of the treatment, to which the so-called Kaufmann method was used, was to get an improvement as quickly as possible. German doctors counted on quick success, preferably in one session, so that the patient could quickly return to the front. The sick were electrocuted and starved. Their correspondence was suspended and even locked in the dark. This brutal treatment was to convince them that returning to the front would be better than staying in the hospital.

The German "method" worked, although, as might be expected, only in the short term. After returning to the unit, many of the soldiers experienced a recurrence of disorders. Bestial treatment also aroused strong opposition, not only from the sick, but also from the public. In 1918, the matter was even raised in a debate in the Reichstag, emphasizing the brutal nature of the therapy.

German soldiers suffering from frontline neurosis were offered Kaufmann's brutal method instead of treatment. Illustrative photo.

Under this pressure, the military authorities decided to accuse Kaufmann and apply psychoanalysis, which was much better for the sick soldiers. It was also planned to create special psychoanalytical wards treating neuroses. However, this idea was never implemented. The war was over and other things became more important.

Soldiers of all armies with frontline neurosis were stigmatized as mentally ill. No evidence of war heroism was found in their stories. Meanwhile, although they had no visible injuries, such as wound marks or disability, they were just as deeply marked by the war. And they usually struggled with trauma for the rest of their lives.

Inspiration

World War I through the eyes of a little boy. Will he be able to find and heal his missing father? We recommend John Boyne's book "Stay, then fight" published by the Replika publishing house, which inspired me to write this article.