The Russian tsar lost her overconfidence. On July 4, 1610, he had an overwhelming advantage over the enemy. However, he managed to approach him at night, surprise him almost in his sleep and push him on the defensive. How did it come about?

The first years of the 17th century were a period of unprecedented turmoil for Russia. After Tsar Fyodor's childless death, the Rurikov dynasty that had ruled since ancient times. The struggles for power became more and more fierce, and finally the throne was taken over by a usurper with the help of Polish magnates - Dmitri called the Self-Prophet.

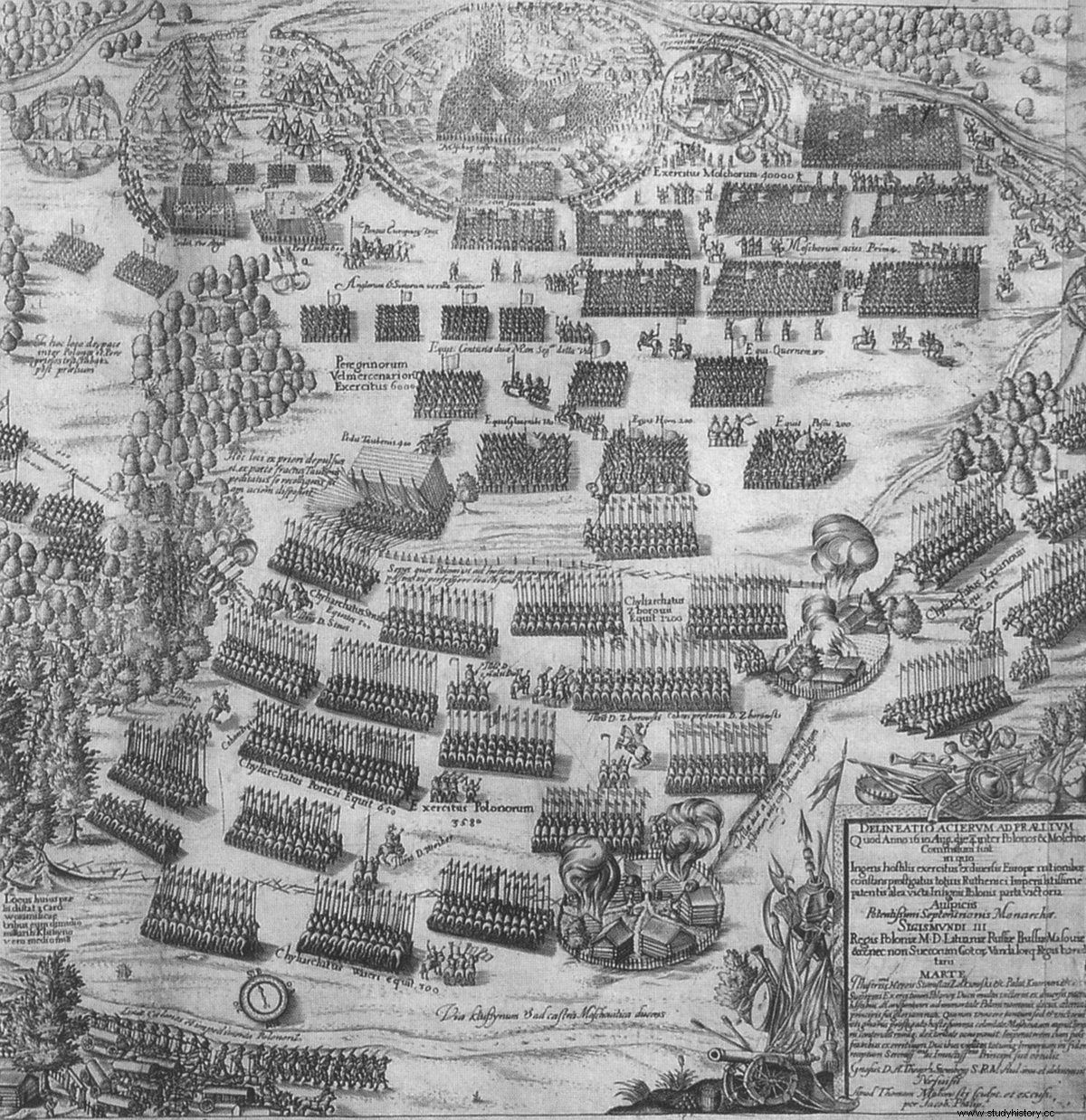

A fragment of a painting by Szymon Boguszowicz depicting the battle of Kłuszyn in 1610.

Nor did he stay in the Kremlin too long. He was captured, brutally tortured, and his body dismembered, burned and fired from a cannon. Wasyl Szujski, the ringleader of the rebellion against the ruler, took over. Soon, however, a man appeared again claiming to be Dmitri - supposedly miraculously saved from execution … Chaos was only building up.

Towards war

The year was 1608. Support for Tsar Vasyl was diminishing. The cities one by one passed under the authority of the Self-proclaimed II, and the most ardent supporters of Szujski hesitated. Moscow was besieged, and the area up to the Volga River was plundered. Help came from the only possible side. Being afraid of Polish influence in Russia, the Swedes who had been at war with Russia so far agreed to peace, albeit at a high price.

The Swedish-Russian agreements hit the interests of the Republic of Poland and were considered by the Polish lords to be a sufficient reason for war . The intention of Sigismund III was to defeat Wasyl Szujski and throw him from the throne. As a consequence of the personal union, which was later to be concluded, the united Republic and Moscow were to attack Sweden together.

Sigismund III Vasa, declaring war on Moscow, hoped to lead to a Polish-Russian personal union.

In 1609, Zygmunt at the head of the army approached Smolensk. The siege began, which stopped the Polish army for two years. And then, when it seemed that the whole campaign would not bring the hopes placed on it, there was a clear proposal by a group of influential Russian boyars to place the royal son of Władysław Vasa on the Moscow throne. Even though preliminary terms of the deal had been agreed in February, things did not move forward. Months passed and the king was still stuck at the walls of Smolensk.

The right man in the right place

At the turn of May and June 1610, bad news reached the Polish army, tired of the siege. Osipov, occupied by the self-proclaimed man, fell. The Swedish-Russian army led by General Everhardt Horn approached the Biała Fortress, previously conquered by Poles headed by Aleksander Gosiewski. And straight from the east, the tsar's brother Dmitri Szujski, assisted by the advice of an experienced Swedish general, Jakub Pontus de la Gardie, set off.

King Zygmunt understood how hopeless he could find himself if he continued to protrude passively near Smolensk. The mission of detaining Szujski entrusted the field hetman of the crown to Stanisław Żółkiewski.

On June 6, the Hetman set off. Fortunately, he had a way of multiplying his own small army so far. He summoned Polish regiments to Szujsk, previously stationed in Wiaźma (Marcin Kazanowski), Tsar's Zajmiszcz (Samuel Dunikowski) and Szujsk himself (Aleksander Zborowski). Gosiewski was also supposed to show up at the assembly point, but as he was besieged, he could not get out of Biała. It was only the threat of relief from Żółkiewski that the enemy forces retreated and unlocked the city.

After seizing the banner from Szujsko, Żółkiewski, at the head of the eight or even ten thousand "corps", set off towards the Tsar's Zajmiszcz. Under this small, well-fortified fortress, a certain Hrehory Wołujew, eight thousand people, Russians and foreign regiments, stood. With the already well-worn Moscow custom, he surrounded the castle with several lancets - small earth and wooden fortifications and started a blockade of the Polish deposit.

On June 24, Żółkiewski arrived at the scene. For nine days neither side was able to beat the opponent or at least force him to surrender. Wołujew knew about the approaching Shujski's army to the rescue. Such news was effective in raising morale.

Cichusieńko left the camp

When Niewiadorowski returned from the drive on 3 July and it was clear that Prince Dymitr Szujski and General de La Gardie were dangerously close to Tsarovy Zajmiszcz, hetman Żółkiewski began to act with his own energy. After a brief deliberation it was decided to separate the forces and attempt to capture the auxiliary army.

Officers bustled around the banners, preparing them to march out of the camp. However, they did it calmly and without unnecessary noise. "And so, with God's help, an hour before Saturday evening we got on the horses and quietly left the camp [we] left the camp in a few rots," wrote Samuel Maskiewicz, companion of the Hussar banner.

A 17th-century portrait of Stanisław Żółkiewski. It was thanks to his genius that we achieved the victory at Kluszyn.

The light banners of petyhorts (almost 300) followed, followed by armored men (nearly 700) and hussars (five and a half thousand). In the middle of the column, the infantry (200) marched between the cavalry, leading two cannons, which, moreover, got stuck in the mud, blocking the road. This slowed down the march, so when the petyhorts emerged from the forest against enemy regiments, they had to wait a long time for the infantry and hussars to arrive.

We would wake them up uncoated

The enemy was asleep. There were no outposts around; Szujski did not send driveways. He was sure of his safety, and at the same time he did not think that the Poles would meet him. The first wake-up trumpets sounded when Żółkiewski's troops were already standing nearby.

De la Gardie was surprised when, leaving the tent, he saw the glow of the fires and the banners of the Republic of Poland, well lit by the rising sun. By no means did they stand idle, because the hetman ordered the fences to be destroyed and the cottages set ablaze.

It took almost an hour to clear the foreground. During this time belated banners were coming. The Zborowski regiment stood on the right wing. Mikołaj Ostrś went to the left. Kazanowski and Dunikowski spread their banners on the right side of Zborowski's ride. The infantry entered the center between Zborowski and Ostrusz. The Cossacks stood on the edge of the left wing, while Żółkiewski, with the reserve, stood in the second line behind the Ostrich regiment.

Our troops surprised the Russians in a dream. The illustration shows a 17th-century copperplate depicting the Battle of Kłuszne.

Meanwhile, Szujski and de la Gardie were rapidly forming ranks; two armies - foreign and Russian - lined up in two places . De la Gardie had five thousand men with him, mostly infantry:Swedes, Germans, Spaniards, French, English and Scots. This conglomerate of nations has based its right wing against the marshes and forest. In front of the first row of the infantry armed with pikes and muskets, a wooden fence rose, giving people excellent protection. There was a reapers at the back.

Szujski spread his 30,000 on the meadow by the river. He set the ride from the forehead. Further in the squares alternately infantry - shooters - and cavalry. While the shooters were a trained and dangerous formation, the cavalry was recruited from the nobility on the basis of a mass move. This was reflected in their armament and bravery. No wonder then that hetman Żółkiewski decided to break them first, ignoring the enormous numerical advantage of the enemy.

It happened ten times that it came to the case

The right wing hussars struck first. It plunged deep into the enemy's ranks, and then vanished in the Moscow "moth innumerable". The lances crumbled and there was an arduous fight with sabers and koncerze. The Poles trained in fencing dominated the Russians and with difficulty, but consistently, made their way from the encirclement. For the first one, the hetman sent another banners of both hussars and armored into battle, while the knights, exhausted from fighting, drove to the rear, rested to set out on fire again.

General de la Gardie did not stand passively, but ordered his subordinates to strike the Ostrich and Cossack banners following him with musket fire. Only the arrival of infantry with falconets improved the effectiveness of Polish attacks. As a result, meager Polish artillery drove the German troops away from under the fence . Now the cavalry had an easier job.

However, the decisive moment of the battle came on the Moscow flank. Kniaź Szujski, so far only defending himself against the charges, "seeing us already weakening, he ordered two reiter's cornet, who stood ready against us, to meet us".

Rajtaria hit the so-called caracol. The equestrian square moved out into the open space in front of the hussars. A volley boomed and, according to Western martial art, the first row of reiters broke in half, and the riders on either side of the arena left at the end, reloading their pistols. Meanwhile, another group raised their pistols, but before the soldiers fired a volley, the hussars ran into them, "and those, having forgotten to punch, [...] handed the back and ran into all of Moscow [...] and mixed its ranks."

Charging hussars near Kłuszyn.

Falconet volleys on the foreign wing and the defeat of the reiter on the Moscow wing determined the victory in the first phase of the battle. The enemy either fled the battlefield or took refuge in camps, which meant the outcome of the battle was still pending , and the Poles faced the arduous conquest of the ramparts. And now the Hetman's letters sent to foreigners have borne fruit. Żółkiewski's conditions were reasonable, so some regiments surrendered, and some (reportedly as many as 2,500) were paid for by the Commonwealth.

The cornered Szujski hesitated for some time whether to fight on, but seeing the deviation of the alien regiments and the poor morale of his own people, he fled. And behind him followed the boyars and all the army. "We drove them two or three miles" - Maskiewicz remembered.

A missed victory

The success in the clash near Kłuszyn spoke about the strength of the Polish army, especially the cavalry, but also about the capabilities of the leader. The road to Moscow was free, and the time of Władysław's enthronement was fast approaching. Indeed, when Żółkiewski approached the Russian capital, the tsarist throne was empty. Szujski was overthrown by a group of boyars who were counting on a relationship with Poland.

The agreement reached by the hetman in August 1610, however, did not satisfy King Sigismund III. And although the Poles reached the Kremlin and made themselves at home in the Tsar's headquarters, they soon had to face another fight, doomed to lose.

Find out more:

- Andrusiewicz A., The history of great sadness , Publishing House "Śląsk", Katowice 1999.

- Czapliński W., Władysław IV and his times , Wiedza Powszechna, Warsaw 1972.

- Pole W., For the Kremlin and the Smolensk region. Poland's policy towards Moscow , Scientific Publishers of the Nicolaus Copernicus University, Toruń 1995

- Wisner H., King and Tsar. The Republic of Poland and Moscow in the 16th and 17th centuries , Book and Knowledge, Warsaw 1995.

- Wójcik Z., History of Russia 1533–1801 , Polish Scientific Publishers PWN, Warsaw 1971.

- Żółkiewski S., The beginning and progress of the Moscow war , Universitas, Krakow 2009.