The textbooks build the image of Napoleon Bonaparte as the savior of Poles, who, like a knight on a white horse, liberated them from his possessive yoke. However, the truth is quite different. And French troops were greeted with more shouts of terror than cheers.

When Napoleon decided to attack Russia, joy reigned among the highest strata of Polish society. The Polish nobility showed considerable patriotic or even amok, according to the title of the new book by Sławomir Leśniewski. The emperor expected thousands of recruits in the country to join him. As Jakub Hermanowicz describes it in his history guide presenting Bonaparte's stay in Poland:

The entire Greater Poland was engulfed in a patriotic frenzy:young men stormed recruiting points, women massively donated gems for the emerging army, landowners voluntarily passed higher taxes than expected. The Poles actually decided to prove to Napoleon that they were worthy of being a nation.

After this comment, it would seem that everyone welcomed the French God of War like a savior. Nothing could be more wrong. 600,000 soldiers marched on Russia, followed by thousands of civilians and caravans. Napoleon's plan was to reach the Russian border quickly, cross it and defeat the tsar. The emperor, hitherto known as a military genius, seemed to have forgotten one thing altogether - the military must eat.

The food warehouses created on the order of Bonaparte were intended only for the French army, while representatives of other nations also went with him to the east. As Digby Smith describes it in the book devoted to the so-called Second Polish War, it was simply impossible to provide food for Napoleon's "Golden Horde" in the lands of the economically ruined Duchy of Warsaw:

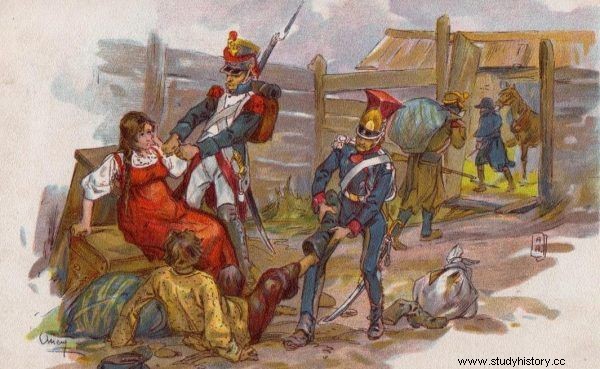

In this situation, the commanders of the unfortunate line troops, deprived of supplies from the warehouses, faced a difficult choice:to take what they needed forcibly from those peasants who would not voluntarily give up your sparse livestock consisting of cows, sheep, poultry, or starve yourself.

Stanisław Wolski, An episode from Napoleon's Russian campaign 1812 (photo:public domain)

Like liberators, yet bandits?

The military did not intend to suffer themselves, let alone expose them to the scarcity of their soldiers. So a wave of looting, which the Polish lands had not seen for a long time, began. Villages and towns were completely plundered. The local population, theoretically belonging to the allied nation, was treated as inhabitants of the conquered country. Peasants were thrown out of their homes and their huts were demolished, taking the building materials needed to build military camps.

The columns of the Grand Army did not care that they were marching through the center of the field. Soldiers grazed their horses on young crops. This year's yield was supposed to be extremely meager, because what the animals did not eat, they trampled with their hooves. It ended badly for horses as well - unripe grain is harmful, so they suffered from heavy colic, causing cavalrymen to lose their mounts before they could face the enemy. The commander of one of the regiments, a native of Piedmont, Giuseppe Venturini, reported that:

While requisitioning food products as instructed, "condemned two or three hundred families to begging." The local population did not want to sell or give away their hunger supplies, so the soldiers took them by force. The French supply system took the form of robbery by itself. And things were getting worse quickly.

The effects of such behavior of the soldiers of the French emperor did not have to wait long. Until recently, the Great Army and its leader Napoleon were welcomed in Polish cities with triumphal arches and illuminations. When the local population found out what the smell of the French "liberation from the power of the invader", they quickly changed their attitude. It was very bluntly described by Adam Zamoyski:

A Polish officer, driving through the country to catch up with the army, found himself in an area of total devastation. All the windows had been broken, all the fences had been pulled down for firewood, and many houses had been half-torn down; the corpses and the heads and skins of the slaughtered cattle lay by the side of the roads, gnawed by dogs and pecked by birds of prey; people fled when they saw a uniformed rider.

Bread and salt?

When the Great Army crossed the Nemunas, the soldiers were made to understand that they were in enemy territory. Then they showed what they can do. Not caring about the fate of the population, they used it as much as they could. The diaries wrote about excesses including the robbery of churches, insults of cemeteries and rape. The attitude of Napoleon's soldiers is perfectly illustrated by the case of a certain Józef Eysmont.

The landowner was extremely pleased with the arrival of French troops. He even welcomed them in his estate with traditional bread and salt. The French thanked him beautifully for this - emptying his barns and stables, cutting the grain ripening in the fields, robbing his house and destroying everything they could not take, and even breaking all the windows. The liberators left him and the surrounding peasants in complete ruin. Nobody could blame these Poles if they changed front and started cursing Napoleon and the day they heard his name!

Napoleonic soldiers plundering civilians during the Russian campaign of 1812 (photo:Alexander Petrowitsch Apsit, public domain license)

Napoleon's soldiers were tired, and in addition, according to Sławomir Leśniewski in his new book 'Napoleon's amok of Poles " , just physically weak. Civil authorities in Poland did not pay attention to their health while recruiting recruits. What's more:

The landed gentry "who all too often replaced a poor tramp, recruited for a modest tip, in place of a needed farmhand-recruit". As a consequence, there were thousands of sick and marauders left on the way, who could not stand the hardships of walking in the wilderness, first in the rain streams and then in the scorching sun.

The army was melting with each kilometer. On June 23, the 5th (Polish) corps of Napoleon's army numbered 30,000 soldiers. At the beginning of August 1812, Prince Poniatowski had only 751 officers and 22,629 soldiers who could stand in the field. As Sławomir Leśniewski comments in "Napoleon's amok of Poles" , compared to the original state, the cavities were as large as after an extremely bloody battle.

French soldiers take the ripe grain. In the background you can see burning rural huts in Dzisna in the former Vilnius Province (photo:Christian Wilhelm von Faber du Faur, public domain license)

Every author writes about losses among soldiers. The subject of the devastation that the march of Napoleon's troops caused among the civilian population is discussed much less frequently. Considering the poor harvest in 1811, military-spread diseases, completely looted farms and burnt houses, the balance sheet must have been tragic. As Polish officers commented on it in their letters:

We don't get the kindness from the locals as we would expect, but that's why you shouldn't risk it.

Unfortunately, the officers were not able to control the debauchery of the soldiers in any way. Napoleon was furious and ordered those responsible for the looting to be killed. It didn't do anything. Initially enthusiastic Poles felt an increasing aversion to Bonaparte and his troops. The peasants mocked that the emperor had come to remove their shackles… immediately with their shoes. The rest began to complain that the Russians had left, stating outright that they were better off during the Tsar's reign.

Check where to buy "Napoleonic amok of Poles":