On Winston Churchill's first day as Prime Minister, Hitler invaded Holland and Belgium. It was preceded by Poland and Czechoslovakia. Over the next twelve months, German bombers would pound the country relentlessly, killing 45,000 Britons and destroying two million homes.

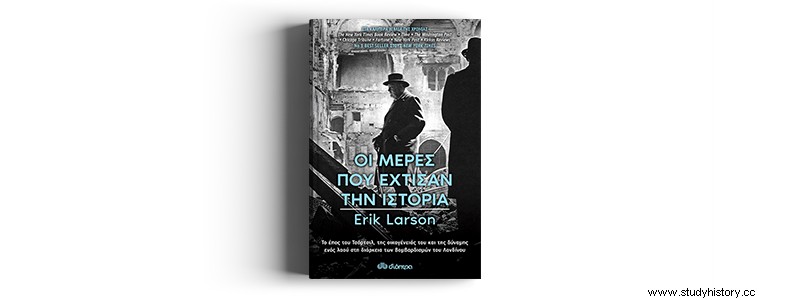

In The Days That Made History released October 6, Erik Larson irradiates the movements and actions of a politician who, for many, is perhaps Britain's most iconic. A man who, if nothing else, managed to inspire his compatriots to fall into battle on the side of the Allies, against the Nazis.

Larson draws his material from diaries, archives and secret service documents - some of which have only recently been declassified - and his writing takes us from the bombed-out streets of London to the Prime Minister's residence and Churchill's country retreat, to the personal his moments with his family and in the discussions with his most trusted advisers.

And he composes with unique vividness the portrait of a true leader who, in the face of destruction, was able with his rhetoric, strategic genius and courage to hold together a people - and a family. After all, the book focuses on the years 1940 and '41, during the German "Blitzkrieg". In essence, as the author himself has stated, it touches on those aspects of a troubled time and sides of Churchill that have not been recorded by history. Bill Gates wrote that the book manages to make the reader feel what it is like to live while waiting for the bombings, through Larson's tight and fast writing that does not resemble a classic history book.

Below, read an exclusive excerpt from the book which secured his Magazine NEWS 24/7 from Dioptra publications. Of particular interest is Churchill's dialogue with his son, as well as the description of the atmosphere and public opinion in the parallel "universe" of the USA, at the time when Britain was deciding to go to war. It is noted here that among Churchill's opponents, there was the King himself who appointed him (George VI) but also Joseph Patrick Kennedy (Joseph P. Kennedy Sr.) , US ambassador to Great Britain who had openly opposed the war with Germany.

He attempted until the beginning of 1940 to meet with Hitler without the prior consent of the American leadership. His attitude, combined with his statements in newspapers that "the war against fascism is not a war for democracy", led, on October 22, 1940, to his replacement.

CHAPTER 3

London and Washington

America loomed large in Churchill's thinking about the war and its eventual outcome. Hitler seemed ready to take over Europe. Germany's air force, the Luftwaffe, was considered much larger and more powerful than Britain's Royal Air Force, and its submarines and cruisers were now seriously impeding the flow of food, weapons and raw materials vital to the island population. The previous war had shown how powerful the United States could be as a military power when it decided to act; now only that country seemed to have the means to balance the sides.

How important America was to Churchill's strategic thinking became apparent to his son Randolph one morning, a few days after Churchill's appointment as Prime Minister, when Randolph entered his father's bedroom at Admiralty and found him standing in front of a basin of water and a mirror shaving. Randolph was home on leave from the Queen's Hussars, Churchill's old regiment, in which he now served as an officer.

"Sit down, my boy, and read the papers until I finish shaving," Churchill told him.

After a few moments, Churchill half-turned to his son. "I think I understand what I have to do," he said.

He turned back to the mirror.

Randolph realized that his father was talking about the war. The remark surprised him, he remembered, because he himself did not see much chance of Britain winning. "You mean we can avoid defeat?" Randolph asked. "Or defeat the bastards?"

Listening to him, Churchill dropped his razor into the basin and turned to look at his son. "And of course I mean we can beat them," he said abruptly.

"Well, I'd like to," said Randolph, "but I don't see how you can do it."

Churchill wiped his face. "I will drag the USA into the war".

In America, people didn't care to crawl anywhere, much less to a war in Europe. This was a change from when the conflict began, when a poll found that 42% of Americans felt that if in the coming months it looked certain that France and Britain would be defeated, they should declare war on Germany and send in the army; 48% said no. But Hitler's invasion of the Netherlands drastically changed public attitudes. In a poll taken in May 1940, it was found that 93% were opposed to a declaration of war, an attitude known as isolationism. Congress had previously codified this antipathy by passing, beginning in 1935, a series of laws, the Neutrality Acts, which strictly regulated the export of arms and ammunition and prohibited their transfer on American ships to any belligerent nation. Americans were sympathetic to England, but now the question was raised just how stable the British Empire was after it had thrown out its government on the same day that Hitler had invaded Holland, Belgium and Luxembourg.

On Saturday morning, May 11, President Roosevelt convened a Cabinet meeting at the White House, in which the new Prime Minister of England became the subject of discussion. The central question was whether he could prevail in this newly extended war. Roosevelt had exchanged messages with Churchill several times before, when Churchill was First Lord of the Admiralty, but had kept them secret for fear of angering public opinion. The general tone of the cabinet indicated skepticism.

Among those present was Harold L. Ickes, Secretary of the Interior, an influential adviser to Roosevelt who was credited with implementing the president's social projects and economic reforms. , which were known as the New Deal. "Apparently," said Ickies, "Churchill is very unreliable under the influence of drink." Ikeys also dismissed Churchill as "too old". According to Frances Perkins, Secretary of Labor, during this council Roosevelt seemed "uncertain" about Churchill.

Doubts about the new prime minister, however, particularly in relation to his drinking, had been sown long before the council. In February 1940, Sumner Welles, US Under Secretary of State, had embarked on an international tour, the "Welles Mission", to meet with leaders in Berlin, London, Rome and Paris in order to makes an assessment of the political conditions in Europe. Among those he visited was Churchill, at that time he was First Lord of the Admiralty. Welles wrote of the meeting in his report that followed:“When I was led into his office, Mr. Churchill was sitting before the fire, smoking a 60-point cigar and drinking a whiskey and soda. It was obvious that he had consumed a lot of whiskey before I arrived.'

The main source of skepticism for Churchill, however, was the American ambassador to Britain, Joseph Kennedy, who disliked the prime minister and repeatedly sent pessimistic reports about England's prospects and the character of Churchill. At one point Kennedy repeated to Roosevelt the gist of a remark Chamberlain had made, that Churchill "had grown into a heavy drinker and his judgment had never been good".

Kennedy, in turn, was not liked in London. The wife of Churchill's foreign secretary, Lord Halifax, loathed the ambassador because of his pessimism about Britain's chances of survival and his prediction that it would be quickly defeated.

"I would gladly kill him," he wrote.

The who is who of the author

Erik Larson studied Russian history and culture at the University of Pennsylvania and received a master's degree in journalism from Columbia University. He has written eight books, six of which became New York Times best sellers. The book The Days That Made History, like its predecessor, Dead Wake:The Last Crossing of the Lusitania, reached No. 1 on the list. His The Devil in the White City, also published by Diopters, was a National Book Award finalist, won an Edgar Award for True Crime, has been consistently on bestseller lists for a decade, and is set to become a mini series from Hulu.

Larson has been a contributing editor to the Wall Street Journal and Time, while his articles they have been published in The New Yorker, The Atlantic Monthly, Harper's and other publications. He has taught nonfiction writing at San Francisco State University, Johns Hopkins University Writing Seminars, and the University of Oregon. He has been honored by the American Meteorological Society for his work on Isaac's Storm, and in 2016 he received the Chicago Public Library Foundation's Carl Sandburg Nonfiction Award. He lives in Seattle with his wife and their three children.