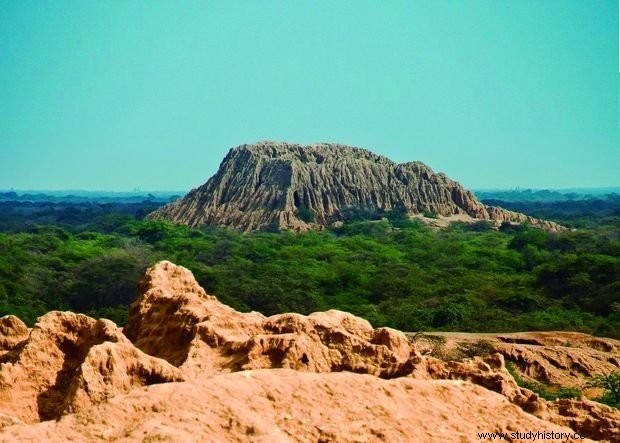

The stillness of the forest in the middle of the desert, where old carob trees reign and their shoots of different ages and shapes and the court of zapotes, faiques and palo verde shines, is the magnificent setting where the traces of the ancient theocratic kingdom of Sicán, in the form of great truncated pyramids that have resisted five hundred years of looting and abandonment. However, despite everything, they are still capable of giving us evidence of their fateful power and greatness:for almost three hundred years, at the end of the first millennium AD, The Sicán made their terrible power the predominant and influential force of a wide territory that included from the south of Ecuador, to the borders of Pachacamac and Ancón. Approximately six thousand hectares are covered by the Pomac Forest Historic Sanctuary, the largest dry forest in America and probably in the world, a set of species of flora and fauna adapted to the exceptionally dry climate of the coastal desert, which lives from the contact found with water underground by the strength of its roots and propitiator of a surprising fauna due to its variety.

Batan Grande is the largest architectural complex of the Sicán culture The Bosque de Pomac Historical Sanctuary is an exceptional and splendid witness to the wonderful symbiosis between man and the rest of nature, as perhaps there is no other part of the planet.

Batan Grande is the largest architectural complex of the Sicán culture The Bosque de Pomac Historical Sanctuary is an exceptional and splendid witness to the wonderful symbiosis between man and the rest of nature, as perhaps there is no other part of the planet.The power of Sicán Perhaps not a unique case in the rich history that has transpired in the Peruvian territory, populated by valuable cultural manifestations ignored, the memory of Sicán has taken time to impose itself in the eyes of Peruvians and the world. The great revealer of the importance of Sicán, the Doctor Izumi Shimada, characterizes it chronologically based on studies of its ceramics, in three periods:Early Sicán, which would have existed between 700 and 900 AD, Middle Sicán between 900 and 1100 AD, and Late Sicán between 1100 and 1350 AD. It is to Sicán Medio, however, that we must attribute the most important contribution and legacy in works of fine metallurgy, ceramics, refined technique and forms of coexistence in nature, that a very modern Sicán Museum – intensely promoted by Dr. Shimada and obtained thanks to Japanese cooperation – it doesactically exposes us to a few kilometers from the forest where such vestiges were found. Not the only ones, however. It can be safely affirmed that almost eighty percent of the ancient objects carved in gold and other metals, coming from our territory, which are in private collections and museums in Peru and outside Peru, and which cause the admiration of the world for the mastery of our artisans come from Batán Grande, a name by which the area where the center of Sicán power was located is also known, in what is now the Pomac Forest Historic Sanctuary.

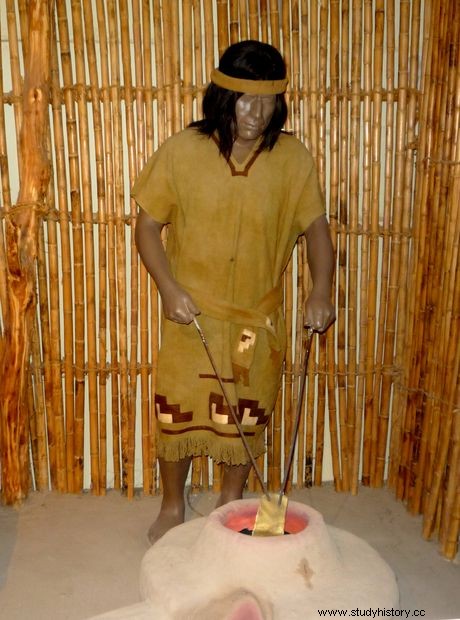

Truncated pyramidal structures are a hallmark of the Sicán culture. The truncated pyramids, which were centers of religious worship, where the presence of many tombs betrays a certain probable worship of ancestors, were combined with public platforms. The mural decoration always focuses on the central character, a god presented as a winged-eyed cutthroat, who carries a head in one hand and a ritual tumi in the other, the same one that the Mochicas feared and who had already frequented these lands since many centuries before and which, later, the Chimú lords will assume. Sicán has, however, its own personality. It is the result of the fusion of two of the main cultural traditions of the Andean territory, the Mochica heritage on the north coast and the Tiahuanaco-Wari influence of the southern highlands. The result is creative and original. The visit to the Sicán Museum allows us to appreciate the quality of the work of those artisans. Where the exquisite ceramics are only surpassed in awe by the brilliance of the metal work. Although gold alloy objects appear more attractive to visitors, the greatest success of their art lay in the large-scale smelting of arsenical copper or arsenical bronze, an alloy that offers superior ductility, hardness and greater resistance to corrosion. The ovens in which their artisans worked required a lot of labor, materials, coal and strong currents of air that were supplied by the force of the human lung. All this has been reconstructed for the visitor to the Museum, in a vivid and didactic way.

Truncated pyramidal structures are a hallmark of the Sicán culture. The truncated pyramids, which were centers of religious worship, where the presence of many tombs betrays a certain probable worship of ancestors, were combined with public platforms. The mural decoration always focuses on the central character, a god presented as a winged-eyed cutthroat, who carries a head in one hand and a ritual tumi in the other, the same one that the Mochicas feared and who had already frequented these lands since many centuries before and which, later, the Chimú lords will assume. Sicán has, however, its own personality. It is the result of the fusion of two of the main cultural traditions of the Andean territory, the Mochica heritage on the north coast and the Tiahuanaco-Wari influence of the southern highlands. The result is creative and original. The visit to the Sicán Museum allows us to appreciate the quality of the work of those artisans. Where the exquisite ceramics are only surpassed in awe by the brilliance of the metal work. Although gold alloy objects appear more attractive to visitors, the greatest success of their art lay in the large-scale smelting of arsenical copper or arsenical bronze, an alloy that offers superior ductility, hardness and greater resistance to corrosion. The ovens in which their artisans worked required a lot of labor, materials, coal and strong currents of air that were supplied by the force of the human lung. All this has been reconstructed for the visitor to the Museum, in a vivid and didactic way. Sicán clothing that houses the Site Museum.

Sicán clothing that houses the Site Museum.  Recreation of the goldsmith work that characterized Sicán The magic of the forest Standing before the tree they call millennial, an ancient carob tree almost five hundred years old that displays all its wisdom in long branches that have not yet expired, and that continue to produce abundant fruit, we are not revolted – but rather convinced – by the worship and prayers that the locals surrender to him. The ancient tree is the symbol, together with some other venerable ones, of what the forest must have always meant and that obviously reflects man's dependence on his environment, which he recognized as the providence that allowed him to continue living. The forest has a tree emblematic, the carob tree (Prosopis pallida), present throughout the northern part of the territory but which has a concentration point here in Pomac. Its roots sink into the ground until they reach the water table and some have been found that have reached up to sixty meters to dig for water. Animals eat its leaves, its fruits serve as fodder, but also for human consumption, especially through the extract called algarrobina. The flowers provide excellent nectar for the beekeepers' bees that have settled in the area and produce honey of good quality and flavor, as well as abundant pollen. The dry leaves are used as excellent fuel and its ample branches and leaves provide the necessary shade to make the aridity of the desert habitable. The carob tree is accompanied by the sapote, second in presence, smaller but with great virtues, the faique, the paloverde , shrubs such as vichayo and cuncuno, as well as cacti hills. Every so often – about a decade – El Niño appears and that causes intense rains to occur. As a result, herbaceous species emerge that make up rich and ephemeral meadows, the seeds of the trees germinate, often enriched by the manure of the animals after consuming the fruits, and the entire forest regenerates.

Recreation of the goldsmith work that characterized Sicán The magic of the forest Standing before the tree they call millennial, an ancient carob tree almost five hundred years old that displays all its wisdom in long branches that have not yet expired, and that continue to produce abundant fruit, we are not revolted – but rather convinced – by the worship and prayers that the locals surrender to him. The ancient tree is the symbol, together with some other venerable ones, of what the forest must have always meant and that obviously reflects man's dependence on his environment, which he recognized as the providence that allowed him to continue living. The forest has a tree emblematic, the carob tree (Prosopis pallida), present throughout the northern part of the territory but which has a concentration point here in Pomac. Its roots sink into the ground until they reach the water table and some have been found that have reached up to sixty meters to dig for water. Animals eat its leaves, its fruits serve as fodder, but also for human consumption, especially through the extract called algarrobina. The flowers provide excellent nectar for the beekeepers' bees that have settled in the area and produce honey of good quality and flavor, as well as abundant pollen. The dry leaves are used as excellent fuel and its ample branches and leaves provide the necessary shade to make the aridity of the desert habitable. The carob tree is accompanied by the sapote, second in presence, smaller but with great virtues, the faique, the paloverde , shrubs such as vichayo and cuncuno, as well as cacti hills. Every so often – about a decade – El Niño appears and that causes intense rains to occur. As a result, herbaceous species emerge that make up rich and ephemeral meadows, the seeds of the trees germinate, often enriched by the manure of the animals after consuming the fruits, and the entire forest regenerates. The ancient tree, an ancient sentinel carob tree of the Pómac Forest The Pomac forest is the main refuge for wildlife that has fully adapted to this ecosystem, to the point of being many of the endemic species. This is the case of the chiroque, the white-naped squirrel and others threatened with extinction, such as the lopper, the falcon, the wild cat, the anteater, the popular huerequeque and others that together amount to forty-one species of birds, seven mammals and nine of reptiles, recognized today. They have left with human activity and with the gradual loss of contact with the high Andean areas, previously linked through a biological corridor, the deer, the pumas, the white-winged guans and the condor. Impressive sum of animal species that the usual common sense cannot imagine in the middle of the desert and that the dry forests manage to shelter. However, the dry forests have been coveted for the quality of their wood especially and the usefulness of their leaves. and fruits. While the pre-Hispanic man was very careful in the use of what was vital for his survival, the arrival of other visions of the world with the conquest and more accelerated search for fuel in recent times and to this day, brought devastation. large areas that were used for firewood and charcoal by rural populations and cities that were appearing on the coast. These arid ecosystems with little rainfall, where plants are subjected to almost permanent water stress, have little rainfall and a temperature ambient temperature of 27° C, on average. The rich flora and fauna established and developed there have adapted in healthy coexistence with the human component that knows how to establish a harmonious relationship with the whole, generating an interdependence of mutual benefit. Thus, there are tens of thousands of peasant families who have dry forests as a source of livelihood and live in the shelter of these ecosystems. The regulation of the water cycle of the coastal basins, the control of erosion and the fight against desertification and the maintenance of water quality depend on its existence – and this was intuited by pre-Hispanic man.

The ancient tree, an ancient sentinel carob tree of the Pómac Forest The Pomac forest is the main refuge for wildlife that has fully adapted to this ecosystem, to the point of being many of the endemic species. This is the case of the chiroque, the white-naped squirrel and others threatened with extinction, such as the lopper, the falcon, the wild cat, the anteater, the popular huerequeque and others that together amount to forty-one species of birds, seven mammals and nine of reptiles, recognized today. They have left with human activity and with the gradual loss of contact with the high Andean areas, previously linked through a biological corridor, the deer, the pumas, the white-winged guans and the condor. Impressive sum of animal species that the usual common sense cannot imagine in the middle of the desert and that the dry forests manage to shelter. However, the dry forests have been coveted for the quality of their wood especially and the usefulness of their leaves. and fruits. While the pre-Hispanic man was very careful in the use of what was vital for his survival, the arrival of other visions of the world with the conquest and more accelerated search for fuel in recent times and to this day, brought devastation. large areas that were used for firewood and charcoal by rural populations and cities that were appearing on the coast. These arid ecosystems with little rainfall, where plants are subjected to almost permanent water stress, have little rainfall and a temperature ambient temperature of 27° C, on average. The rich flora and fauna established and developed there have adapted in healthy coexistence with the human component that knows how to establish a harmonious relationship with the whole, generating an interdependence of mutual benefit. Thus, there are tens of thousands of peasant families who have dry forests as a source of livelihood and live in the shelter of these ecosystems. The regulation of the water cycle of the coastal basins, the control of erosion and the fight against desertification and the maintenance of water quality depend on its existence – and this was intuited by pre-Hispanic man.  The Pómac forest is home to hundreds of birds, some of them endemic to the region

The Pómac forest is home to hundreds of birds, some of them endemic to the region