The mestizos:the result of the meeting of two worlds Francisco Pizarro had three children with Indian women. One son with Doña Angelina, daughter of Atahualpa Inca, and two with Doña Inés de Huaylas, daughter of Huaina Cápac. They were mestizos; children born from the union between a Spaniard and two Indian women. Many cases of Spaniards and Indians, such as that of the Marquis, occurred during the first conquerors, because their troop lacked women. After them, for many more decades, that link continued to prevail, because more men than women came from Spain.

Imaginary portrait of the Inca Garcilaso de la Vega in Spain. The Spaniard only married one of his class That union was, in any case, a forced union, one more example of colonial rule, because almost all Indian women were taken as concubines and their children considered bastards. The Spaniard could not marry but with Spanish. When the Spanish began to arrive in the Viceroyalty, the Indian concubines and mestizo children were abandoned. On the contrary, during colonial times there were very few cases of miscegenation as a result of the union between an Indian and a Spanish woman. “The children of Spaniards and Indians or of Indians and Spaniards are called mestizos, to say that we are mixed from both nations; it was imposed by the first Spaniards who had children in the Indies; and because it is a name imposed by our parents and because of its meaning, I call it to myself with a full mouth and I am honored with it”, said the Inca Garcilaso de la Vega.

Imaginary portrait of the Inca Garcilaso de la Vega in Spain. The Spaniard only married one of his class That union was, in any case, a forced union, one more example of colonial rule, because almost all Indian women were taken as concubines and their children considered bastards. The Spaniard could not marry but with Spanish. When the Spanish began to arrive in the Viceroyalty, the Indian concubines and mestizo children were abandoned. On the contrary, during colonial times there were very few cases of miscegenation as a result of the union between an Indian and a Spanish woman. “The children of Spaniards and Indians or of Indians and Spaniards are called mestizos, to say that we are mixed from both nations; it was imposed by the first Spaniards who had children in the Indies; and because it is a name imposed by our parents and because of its meaning, I call it to myself with a full mouth and I am honored with it”, said the Inca Garcilaso de la Vega.The mestizos suffered an atrocious discrimination However, the social class of the mestizos was totally discriminated against, without being accepted by the republic of the Spaniards or by the republic of the Indians. Among the restrictions that the mestizos had, are the following:1. They could not exercise public functions. 2. They were prohibited from carrying weapons, a distinction that was reserved for the Spanish, Creoles and caciques. 3. They were generally not accepted into seminaries or religious orders. They couldn't be priests. 4. They could not be appointed as caciques, a position that was destined only for the sons of the Inca nobility. 5. Some lived at the expense of their parents, serving in their homes or farms. Others learned and exercised some trades. Many became laborers or peasants. But, demographically, they were gaining more and more importance. The data on the population by race that we have from the 18th century show that the mestizos had increased considerably in the Viceroyalty of Peru. Meanwhile, the indigenous population had dangerously decreased.

A notable mestizo:the Inca Garcilaso de la Vega He was born in Cusco, which he called Cozco, on April 12, 1539. He was baptized with the name of Gómez Suárez de Figueroa . At that time, children could use any of their parents' surnames and so they also called him as a tribute to one of his father's ancestors. At the age of 24, he changed his name to Gómez Suárez de la Vega and, later, to Garcilaso de la Vega. In order not to confuse it with the name of another famous Spanish writer (Garcilaso de la Vega), it is called today:Inca Garcilaso de la Vega. His father was the Spanish captain Sebastián Garcilaso de la Vega, who had arrived with the hosts of Pedro de Alvarado in Peru in 1534 and stayed to reinforce Francisco Pizarro and Diego de Almagro, and his mother was the ñusta Isabel Chimpu Ocllo, granddaughter of Túpac Yupanqui, niece of Huaina Cápac and cousin of Huáscar and Atahualpa. The Spanish captain no longer benefited from Atahualpa's treasure but obtained an encomienda in Cotanera, on the banks of the Apurímac River, and settled in Cusco, in a palatial house with Inca foundations and Spanish arches and balconies. This house still exists in the Plaza del Regocijo. Captain Garcilaso de la Vega was one of the actors in the civil wars between the Spaniards and was not always on the same side, so they made fun of him saying:"... the loyal one for three hours." In the battle of Huarina (10-20-1547; southeast of Lake Titicaca), he fought alongside Gonzalo Pizarro. It is said that he lost his mount and Captain Garcilaso de la Vega gave him his, a gesture that contributed to the insurgent's triumph. After Gonzalo Pizarro was defeated by the peacemaker La Gasca and executed, Garcilaso de la Vega returned to the royalist hosts and, despite the fact that his Cusco house was looted by Gonzalo Pizarro's supporters, he continued to enjoy some privileges of the Crown. .

Gomez Suarez de Figueroa "Inca Garcilaso de la Vega" What were the early years of the Inca like? It is said that more than a hundred diners attended the house of Captain Garcilaso de la Vega and his wife Isabel Chimpu Ocllo, "almost every day", between Spaniards and noble Indians. The child Gómez Suárez de Figueroa was thus a witness to the daily meeting of two cultures, two ways of life. His parents, for their part, did their best to help him better understand the culture to which they belonged. Isabel Chimpu Ocllo tries to make her son understand the values of her ancestors. She taught him Quechua, her uncle Cusi Huallpa the history of her ancestors and her uncles Juan Pechuta and Chauca Rimachi the rest of the Tahuantinsuyu. For his part, the father, who made sure that he mastered Spanish, entrusted the upbringing of the son to tutor Juan de Alcobaza, who taught him grammar and Latin. Canon Juan de Cuéllar was in charge of perfecting his Latin and Captain Gonzalo Silvestre served as teacher of Spanish history. “Life, by itself, poses serious problems for mestizo children. The father, keeping to the rhythm of his time, does not care much about being loyal to principles, but to people and according to momentary success, so that he goes from one field to another, changing parties easily... Agreed With such metamorphoses, the distinguished bastard will now receive the compliments of Gonzalov Pizarro, now those of La Gasca, now those of Antonio de Mendoza. In the midst of such contradictions and vicissitudes, the Captain's mestizo family lives in absolute uncertainty. While the father alternates his devotions, the children suffer anguish” (Luis Alberto Sánchez). The variable personality of Captain Garcilaso de la Vega also ends up manifesting itself in family disloyalty and the prejudices of the time; he leaves Isabel Chimpu Ocllo and ends up marrying the Spanish Luisa Martel de los Ríos y Lasso de Mendoza, with whom he had two daughters. The Inca princess did it with a squire named Pedrachi. The Inca Garcilaso de la Vega, after the painful separation of his family, continued to live in his father's house

Gomez Suarez de Figueroa "Inca Garcilaso de la Vega" What were the early years of the Inca like? It is said that more than a hundred diners attended the house of Captain Garcilaso de la Vega and his wife Isabel Chimpu Ocllo, "almost every day", between Spaniards and noble Indians. The child Gómez Suárez de Figueroa was thus a witness to the daily meeting of two cultures, two ways of life. His parents, for their part, did their best to help him better understand the culture to which they belonged. Isabel Chimpu Ocllo tries to make her son understand the values of her ancestors. She taught him Quechua, her uncle Cusi Huallpa the history of her ancestors and her uncles Juan Pechuta and Chauca Rimachi the rest of the Tahuantinsuyu. For his part, the father, who made sure that he mastered Spanish, entrusted the upbringing of the son to tutor Juan de Alcobaza, who taught him grammar and Latin. Canon Juan de Cuéllar was in charge of perfecting his Latin and Captain Gonzalo Silvestre served as teacher of Spanish history. “Life, by itself, poses serious problems for mestizo children. The father, keeping to the rhythm of his time, does not care much about being loyal to principles, but to people and according to momentary success, so that he goes from one field to another, changing parties easily... Agreed With such metamorphoses, the distinguished bastard will now receive the compliments of Gonzalov Pizarro, now those of La Gasca, now those of Antonio de Mendoza. In the midst of such contradictions and vicissitudes, the Captain's mestizo family lives in absolute uncertainty. While the father alternates his devotions, the children suffer anguish” (Luis Alberto Sánchez). The variable personality of Captain Garcilaso de la Vega also ends up manifesting itself in family disloyalty and the prejudices of the time; he leaves Isabel Chimpu Ocllo and ends up marrying the Spanish Luisa Martel de los Ríos y Lasso de Mendoza, with whom he had two daughters. The Inca princess did it with a squire named Pedrachi. The Inca Garcilaso de la Vega, after the painful separation of his family, continued to live in his father's house Why did he go to Spain? In the year 1559 his father died. He had become corregidor of Cusco. By will, he bequeathed to his son the Havisca coca farms (in the Paucartambo area) and the sum of four thousand pesos so that he could study in Spain. The Inca could not take possession of the hacienda because, according to the legislation of the time, he had to first pass it on to the legitimate daughters, who died shortly after. The Inca Garcilaso de la Vega completely separated himself from his stepmother because his paternal heritage spurred him on, not only his Hispanic ancestry but also chrematistic privileges. To find both things, he decided to change his course of life at the age of 21, that is, shortly after the death of his father, in the year 1560. He left Cusco and went to Lima . He didn't like that city, with its roofless houses, hot, humid climate, and huge plaza. He was amazed at the remains of the Pachacámac Sanctuary, the archaeological remains of Cañete and other valleys, as well as the view of the Pacific Ocean. Some time later, he embarked in Callao for Spain. After a difficult sea voyage, he arrived in Lisbon, from where he moved to Seville. He arrived at said Spanish port in the year 1561. His trip had taken a year. So he went to Spain to claim the properties of his father and those that had been taken from his mother. After several years of efforts, his response was negative, arguing that his father had saved his life.

The Inca Garcilaso de la Vega was of the same lineage as Atahualpa

The Inca Garcilaso de la Vega was of the same lineage as Atahualpa by part of the mother and descendant of Spaniards on the part of his father. What did he do in Spain? Somewhat disappointed in the Spanish court, he wanted to return to Peru but his uncle Alonso de Vargas persuaded him to stay in Spain, lodging him in the house of Montilla (Córdoba) and adopting him as his son. The Inca helped in the administration of his uncle's assets and dedicated himself to expanding his cultural information. In 1570 Don Alonso de Vargas died. His estate passed into the possession of his widow. When she died she was given to the Inca Garcilaso de la Vega. Between the year 1570 and shortly before his aunt died, the Inca enlisted in the royalist army. Under the orders of Juan de Austria he fought against the Moors in the battle of the Alpujarras, reaching the rank of Captain of His Majesty. In the year 1571 he learned of the death of his mother, which ended with some desire to return to Peru. He even arranged for the sale of his coca farm in Havisca. He was related to the Jesuits of Montilla and other intellectuals of the region, who encouraged him to translate "The Dialogues of Love" and in turn to enter literary creation. In the year 1588 the widow of his uncle and adoptive father Alonso de Vargas died. From then on, the Inca Garcilaso de la Vega enjoyed sufficient economic solvency and was able to dedicate himself fully to writing. They made him a resident of the city of Montilla and he participated in the council. He acquired more houses and vineyards and became a prosperous farmer. He dedicated himself to the sale of wheat and the business of buying and selling horses. But, he got tired of small-town life, he sold all his properties in Montilla and moved to Córdoba. In that city, his circle of friends increased thanks to the support of the local Jesuits and he was able to write his great works.

“He buried himself in her” Inca Garcilaso de la Vega died on April 23, 1616 and was buried in one of the chapels that he himself had built inside the cathedral of Córdoba. In his crypt there is the following text:“He lived in Córdoba with a lot of religion. He died exemplary:he endowed this chapel. He buried himself in it.”

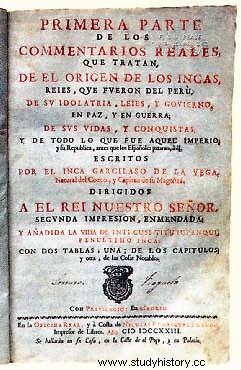

Proem of the “Comments Real” "Although there have been curious Spaniards who have written the republics of the New World, such as Mexico and Peru and those of other kingdoms of that gentility, it has not been with the entire relationship that could be given of them, that I have noticed it particularly in the things that I have seen written about Peru, of which, as a native of the city of Cozco, which was another Rome in that Empire, I have more extensive and clear information than what writers have given up to now. It is true that they touch on many of the very great things that that republic had, but they write them so briefly that even the very notorious ones for me (in the way they say them) I misunderstand. Therefore, forced by the natural love of the country, I offered myself the job of writing these Comments, where the things that existed in that republic before the Spaniards will be clearly and distinctly seen.

What are your works? 1588 - “The Dialogues of Love of León Hebreo” (translation from Italian to Spanish). 1590-"Relationship of the descendants of the famous Carci Pérez de Vargas with some steps of history worthy of his memory". 1605 - “History of Florida and the journey made by Governor Hernando de Soto”. 1609 - “Royal Comments”. 1617 - “General History of Peru”. This work, which is the second part of the "Royal Commentaries", was published after his death.

Cover of one of the first editions of the “Real Comments

Cover of one of the first editions of the “Real Commentsof los Incas". It was printed in two colors in Madrid, in 1628. The "life of Inti Cusi Yupanqui, penultimate Inca" was added. “The origin of the Inca Kings of Peru” Living or dying those people in the way we have seen, God our Lord allowed a morning star to come out of them that in those very dark darkness would give them some news of the natural law and of the civility and respect that men should have for each other. one another, and that his descendants, proceeding from good to better, cultivate those beasts and turn them into men, making them capable of reason and of any good doctrine, so that when that same God, the sun of justice, had for the good of send the light of its divine rays to those idolaters, find them, not so savage, but more docile to receive the Catholic faith and the teaching and doctrine of our Holy Mother Roman Church, as later they have received it here, as will be seen and the other in the discourse of this story; that by very clear experience it has been noted how much quicker and more agile the Indians that the Inca Kings subjugated, governed and taught were to receive the Gospel, than the other neighboring nations where the teaching of the Incas had not yet arrived, many of the which are today as barbaric and brutal as they were before, with seventy-one years since the Spaniards entered Peru. And since we are at the door of this great labyrinth, it will be well for us to go forward to give news of what was in it. After having given many traces and taken many paths to enter into an account of the origin and beginning of the Inca natural Kings who were from Peru, it seemed to me that the best trace and the easiest and plainest path was to tell what I heard in my childhood. many times to my mother and her brothers and uncles and other elders about this origin and principle, because everything that is said about it by other means comes to be reduced to what we will say, and it would be better to know it through the Own words that the Incas tell it, not by those of other strange authors. Thus, my mother living in Cozco, her homeland, came to visit her almost every week the few relatives who escaped the cruelties and tyrannies of Atahualpa (as we will tell in his life), in which visits always their most ordinary The talks were to deal with the origin of their Kings, their majesty, the greatness of their Empire, their conquests and exploits, the government they had in peace and in war, the laws that benefited and favored their vassals. They ordered. In short, they did not leave anything of the prosperous that had happened among them that they did not bring it to account. From past greatness and prosperity they came to present things, their dead Kings wept, their Empire alienated and their republic finished, etc. These and other similar talks the Inca Pallas had on their visits, and with the memory of the lost good, they always ended their conversation in tears and tears, saying:"We exchange reigning in vassalage..." etc. In these talks I, as a boy, often went in and out where they were, and rejoiced in hearing them, as such do not like to hear fables. As days, months and years went by, when I was already sixteen or seventeen years old, it happened that, one day when my relatives were in this conversation talking about their Kings and antiquities, the oldest of them, who was the one who I realized them, I told him:- Inca, uncle, since there is no writing among you, which is what keeps the memory of past things, what news do you have of the origin and beginning of our Kings? Because there the Spaniards and the other nations, their comarcanas, as they have divine and human histories, know from them when their Kings and those of others began to reign and when some empires changed into others, until knowing how many thousand years ago God created the sky and the land, who know all this and much more from their books. But you, who lack them, what memory do you have of your antiquities? Who was the first of our Incas? What was his name? What origin did his lineage have? How did he begin to reign? With what people and weapons did he conquer this great Empire? What origin did our exploits have? The Inca, as if rejoicing at having heard the questions, for the pleasure he received from giving an account of them, turned to me (I had already heard him many other times, but none with the attention that then) and said:-Nephew , I will tell you very willingly; it is convenient for you to hear them and keep them in your heart (it is their phrase to say in memory). You will know that in the ancient centuries all this region of land that you see were great mountains and thickets, and the people in those times lived like beasts and brutish animals, without religion or police, without town or house, without cultivating or sowing the land, without clothing or covering their flesh, because they did not know how to work cotton or wool to make clothing; They lived two by two and three by three, as they managed to gather in the caves and cracks of rocks and caverns of the earth. They ate, like beasts, grasses of the field and roots of trees and the uncultivated fruit that they gave of their own and human meat. They covered their meat with leaves and tree bark and animal skins; others were naked. In short, they lived like deer and savages, and even in women they had become like brutes, because they did not know how to have their own and known them”

The Inca Garcilaso dela Vega, according to the painter

The Inca Garcilaso dela Vega, according to the painterof the Cusco artist F. Gonzales Gamarra

Inca Garcilaso de la Vega;

“Royal Commentaries” of the Incas