To what degree can the torments of a war be represented to the general public? The difficulty is to highlight heroism and sacrifice in the face of the relentless observation of the battlefield. The question of military representation and victims will arise in force during the First World War, when millions of recruits will have to leave their families to go to the front lines. The difficulty is to highlight both heroism and sacrifice on a battlefield.

Postcards:between propaganda and psychological support.

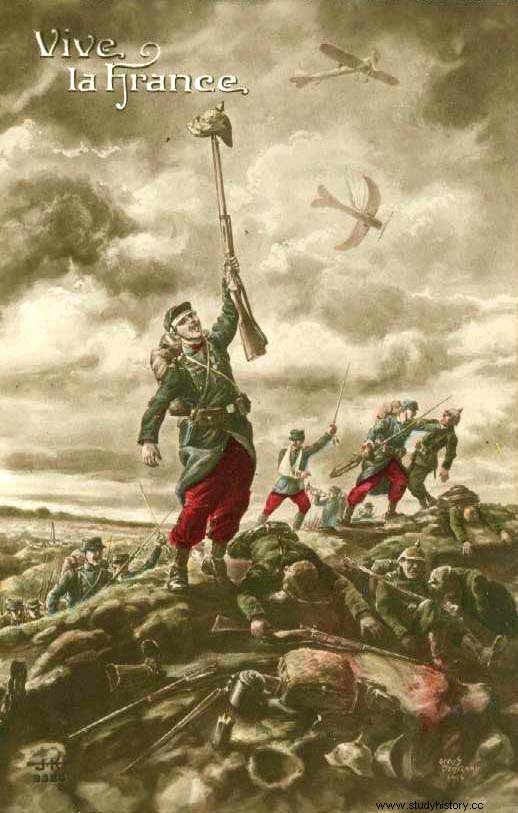

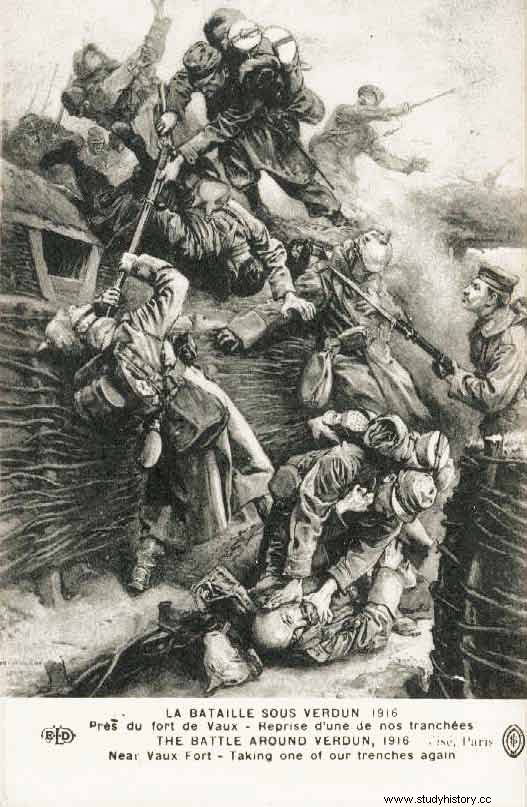

During the first major world conflict, postcards were produced and distributed on a large scale. They had to allay fears, highlight wounded soldiers receiving help in one form or another, but also not evade the observation of omnipresent death. On this last point, and for a very long time, it will circumvent it. Because it was a delicate subject, on which the editors had to keep in mind the sensitivities of the public. The problem was that society itself was divided on what it wanted to see. Attitudes also changed as the war dragged on, and the 19th-century romantic sensibilities that still dominated people's view in 1914 dissipated significantly within two years.

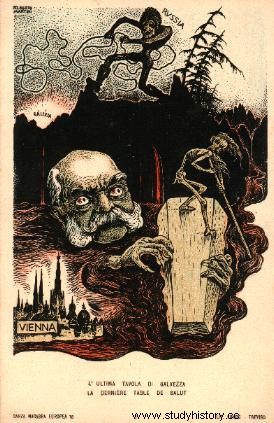

These postcards, unlike war bulletins, help us a lot to understand where other types of documents fail. Their number reflects the quality of the expression of the thoughts of a society. Very often, they use mythical and religious themes rooted in a society to put death into perspective in a soothing context.

While many postcards depicting battle scenes from the Great War mimic 19th century sensibility, there seems to have been a growing tendency to portray combat as more vicious and deadly, even bloody. At a time when so many deaths were to be mourned, was the public demanding a more accurate depiction of the war or was it the influence of sensationalist stories reaching the masses through cheap magazines. Soldiers often expressed frustration with the sanitized way their life at the front was portrayed in the news. Part of the difference may be that most 19th century military artwork was painted after the fact, while Great War postcards served as propaganda to influence an ongoing conflict.

Previously, in depictions, most of the deaths belong to the enemy, implying the superiority and prowess of his own army, if not victory itself. Certain friendly troops must fall to remind us of the real danger they represent, and thus reinforce the bravery and sacrifice of those who continue to fight. This tradition continued during the First World War and explains how most battle scenes were composed on postcards.

Studio shots have also been used extensively for real photo cards expressing military themes. Produced in mock sets, these maps tend to be posed so well that they look like a scene from a theater or a silent movie. They help to separate all the romantic rhetoric that constitutes the general perception of war from its actual violence and destruction.

I had a friend

All the scenes represent insist on self-denial for a greater purpose, they also represent the good death. These men do not die alone or in pain, but play a devoted role with their comrades until the end. In these stories, the dying soldier is not alone, but in the company of a friend. You don't have to have a mysterious spiritual connection to deliver a final message to your family. Such images are not pure fantasy.

This theme was made popular by the poem “The good comrade”, written in 1809 by the Austrian poet Ludwig Uhland. Although inspired by the Tyrolean rebellion against Napoleon, it deals with personal losses rather than political issues, which gave it universal appeal. After its lyrics were adapted into a popular folk tune, it was used as a marching chant by many armies around the world. Although widely sung by the German army during the Great War, the general theme was mass-produced in folk art, and appears as a troop on postcards of all nations.

When the real casualties began to occur, soldiers at the front quickly learned the realities of war. Most of the soldiers died as a result of artillery fire which tore off limbs and riddled bodies with horrific wounds. This death often occurred anonymously, as they never saw the enemy or the weapon that killed them. Postcards tell a very different story

Spiritualism and patriotism.

Many depictions dealing with dying or dead soldiers have a strong religious connotation. The figures around them may be angels, although it is sometimes difficult to distinguish them from allegories of victory. Specific symbolic characteristics exist, but illustrators of the time often based their work more on their own personal inclinations than on classical traditions. Angels are easier to identify when they carry a dead soldier into heaven.

There is never any confusion as to the religious significance of an image when Christ is present, and he is regularly depicted. He is usually found comforting a dying soldier or sending the dead to heaven. Sometimes the figure of Christ can be found in a painful pose, standing over the dead. This type of anti-war message seems to have escaped censors, perhaps because it does not specifically assign responsibility for the tragedy outside of the abstraction of war.

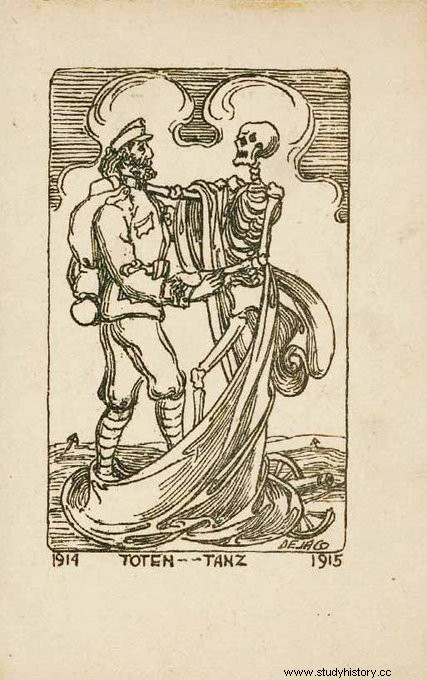

Some cards drawn by artists did not display the usual reassurance message when it came to death. Here, death is the warrior's companion on the battlefield; they became partners in crime. In personification, death can be found by directing the aim of a piece of artillery or a soldier's rifle to ensure that the enemy is eliminated. These cards were probably censored because the traditional use of symbolism to represent the macabre was part of the culture. Death symbols were already used on badges as a symbol of a soldier's prowess and strength. Despite this, the number of cards embracing the macabre was low, either due to censorship or their lack of appeal to actual death.

The Danse Macabre, in which people of various professions and stations of life become acquainted with death personified by a skeleton, was present in medieval art from the beginning of the 15th century. This sermon-based allegory regarding the inevitability of death was popularized a hundred years later by the woodcuts of Hans Holbein the Younger. His approach of showing happy, engaged people in everyday life being embraced by death was so inspiring that it became the norm for other artists. Many have since updated this allegory, but they often continue to work the woodcut as a tribute to the early interpretations to which it is so attached. This was the case during the First World War, when the motif was sometimes used to show soldiers.

Military painting had been refined by the end of the 19th century to represent a larger, more heroic and more dramatic story of war. We can take as an example the military painter Édouard Detaille (1848-1912) who exposed death on the battlefield without detour. Engaged in the 8th mobile infantry battalion of the army, during the war of 1870; he was able to experience the realities of war up close. This experience allowed him to create his famous soldier portraits and depictions, sometimes crude, but historically accurate.

Photography

Photo printed cards depicting the dead are quite rare as it is nearly impossible to capture the correct death on film. The fate of a loved one's body after it dies in a remote location is of great concern to families.

The images of dead soldiers who were willing to sacrifice their lives are regrettable, but the images of dead innocent civilians who should be freed from this unexpected danger presented a real tragedy in the propaganda war. These depictions have been tolerated because they are not intended to speak of the treatment of the dead so much as the barbarity of the enemy. They also remind everyone that this war is a danger for everyone and that everyone therefore has an interest in participating in it. There is often a horror that resides in these images, evoked by the casualness in which the bodies lie in the streets like unwanted pieces of trash. These images not only show death, but also the breakdown of social order.

World War I was one of the first conflicts in which cameras were small enough to be carried around. Canadian soldier Jack Turner secretly, and de facto completely illegally, brought a camera to the front (see below:Battle of Vimy Ridge in 1917).

In the 20th century, professional photographers covered every major conflict, including Robert Capa who covered, among others, the Spanish Civil War, the Second Sino-Japanese War and the D-Day landings. , he was killed by a landmine in Indochina in May 1954. The Second World War will mark a turning point in the way of covering a war spread over several fronts. We can cite the war correspondent Walter Rosenblum who, on June 6, 1944, photographed a young American lieutenant desperately trying to resuscitate a member of their crew. Photographic techniques will therefore continue to evolve, bringing realism to an information-hungry public combined with a new form of incentive to recruit new recruits.

Unlike paintings, which presented a single illustration of a specific event, photography provided the opportunity for a large amount of imagery to come into circulation. The proliferation of photographic images allowed the public to be well-informed in wartime discourse. The advent of mass-reproduced war images not only served to inform the general public, but they served as time imprints and historical records.

Mass-produced images had consequences. Besides informing the public, the overabundance of broadcast images has saturated the market, allowing viewers to develop the ability to disregard the immediate value and historical significance of certain photographs. Despite this, photojournalists continue to cover conflicts around the world.

Find out more

https://www.cairn.info/revue-guerres-mondiales-et-conflits-contemporains-2011-1-page-51.htm

http://centenary.org

http://education.francetv.fr

http://first-war-world-1914-1918.com

http://www.ww1-propaganda-cards.com/alberto_martini(1).html

https://www.pedagogie.ac-aix-marseille.fr/upload/docs/application/pdf/2017-01/dossierpedacartespostales14182.pdf