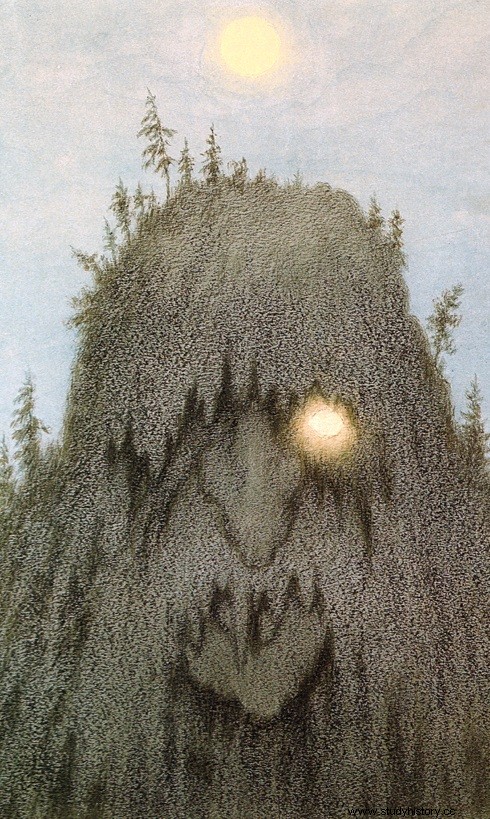

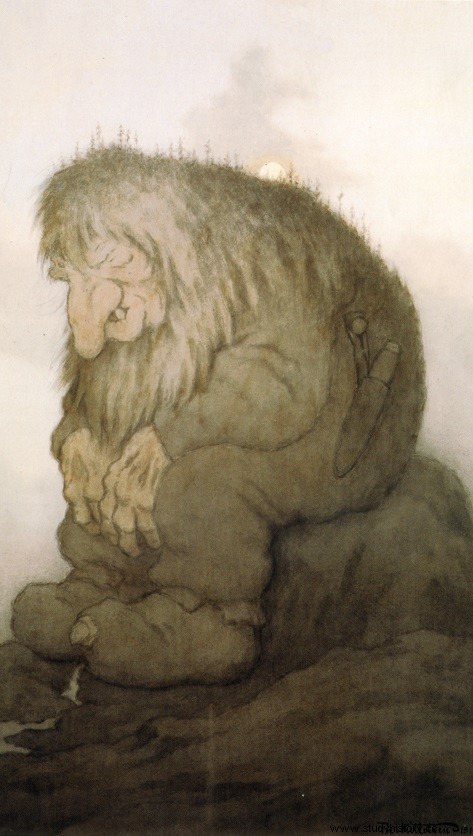

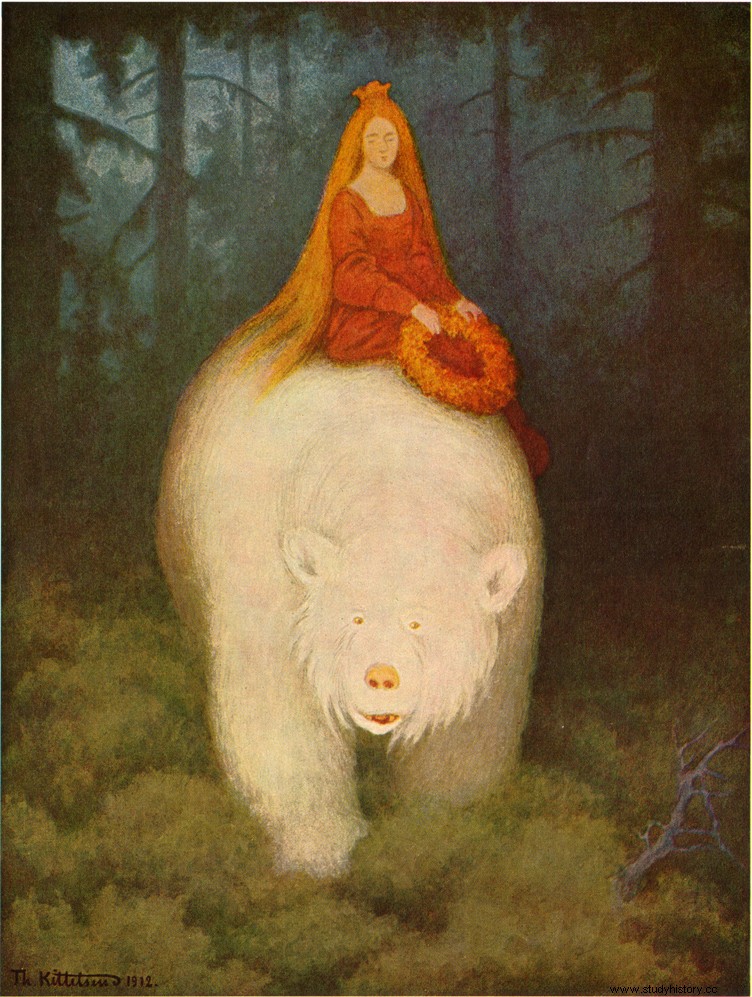

We know that fairy tales are the only truth in life said Antoine de Saint-Exupéry candidly. The Norwegian artist Theodor Kittelsen (1857–1914) can testify to this, he did it all his life. We are talking here about the grand master of legendary creatures called trolls. But far from the distorted definition given to it today, the trolls were indeed sketched in the heart of a snowstorm and by squinting well, one could see the subtle nuances between a skogtroll (troll of forest) and a Sjøtrollet (sea troll).

But his legacy to the world is not only made up of fairies or trolls, his brush also took on a gloomy air as he drew the great plague of the Middle Ages. Nevertheless, we are moving too fast, and it is appropriate to return to the first steps of the young Theodor (Severin) Kittelsen, Norwegian painter, graphic designer and illustrator, famous – you guessed it – for his landscapes and his drawings mainly related to the marvelous.

Born in the small town of Kragerø into a merchant family, he was the second of eight children. From childhood he began to paint. As his father died prematurely, Kittelsen was forced to work from an early age. He also briefly traveled to the Norwegian capital, Christiania and not Oslo at that time, to work there as an apprentice painter. When Kittelsen trained as a watchmaker's apprentice, his owner introduced him to a wealthy philanthropist and art lover Diderich Maria Aall, who helped him get into Christiania art school and paid his fees. of schooling. Kittelsen then studied in the capital for two years, after which he went to Munich to continue his studies.

Three years later, Kittelsen began to have financial difficulties. The paintings brought in little money. As a result, he was forced to return to Norway. At the same time, Kittelsen was serving in the army. After his military service, and in particular thanks to a scholarship, he was able to go to Paris for a short time, then again to Munich. In 1883, our Norwegian globetrotter, together with German artists Erik Werensjöll and Otto Sinding, received an order for illustrations for a three-volume edition of Norwegian folk tales.

As Kittelsen was homesick, in 1887 he returned to Norway and never left. He got a job as a lighthouse keeper on the island of Skomvar (Lofoten Islands). There, isolated, near a wild and exuberant nature, he was inspired to create several series of drawings that were published in separate books (the texts were also written by him). These include “Living in Cramped Conditions” (Fra Livet i de smaa Forholde, 1890), “Lofoten Islands” (Fra Lofoten, 1890-1891) and Witchcraft (Troldskab, 1892).

In 1889 Kittelsen met a girl named Inga Christine Dahl, who was ten years her junior. They got married very quickly.

In the mid-1890s, Kittelsen wrote his most famous book, The Black Death (Norse Svartedauen). The book focused on the plague epidemic that swept through Europe in the mid-14th century and caused the death of millions of people, and Norway was not spared.

In 1908 Kittelsen was awarded the Order of St. Olaf, Norway's highest honor. In 1911 he wrote his autobiography People and Trolls, Memories and Dreams. Autobiography ”(Folk og Trold, minder og drømme. Selvbiografi).

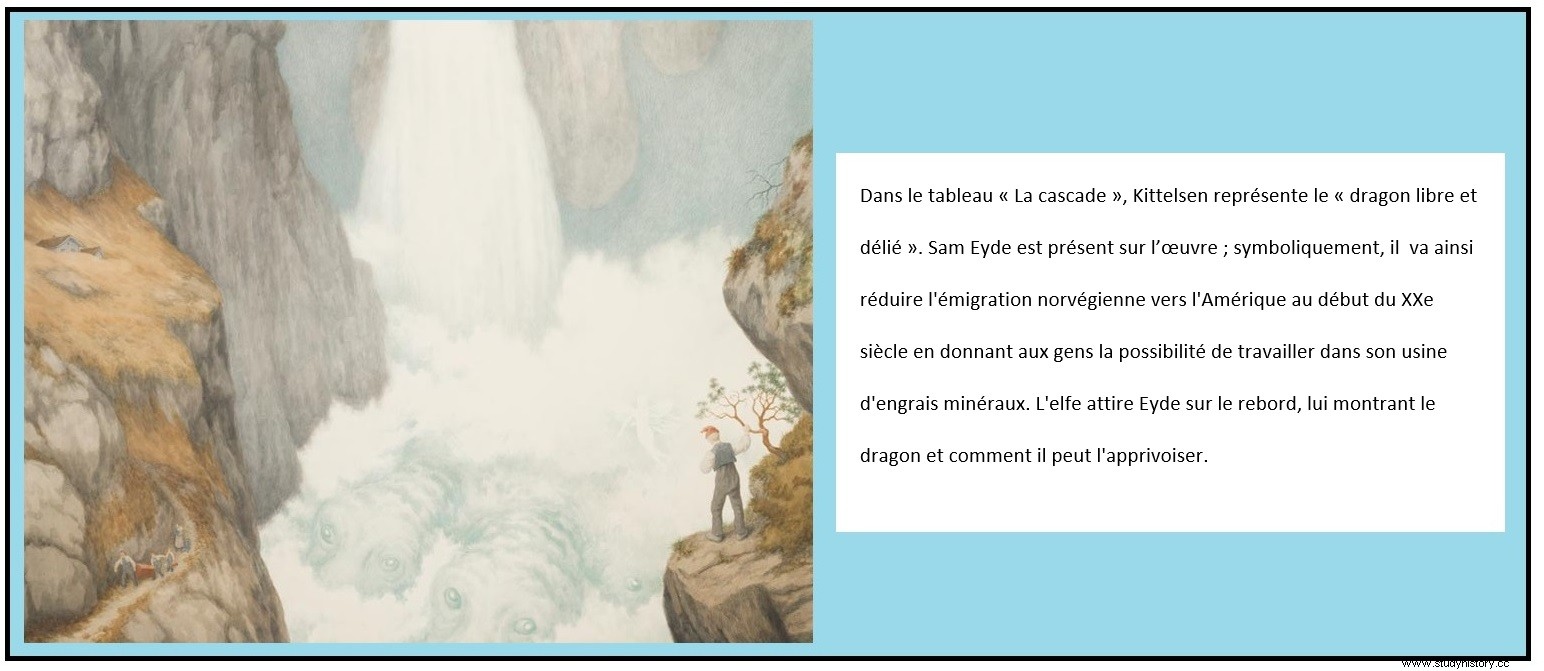

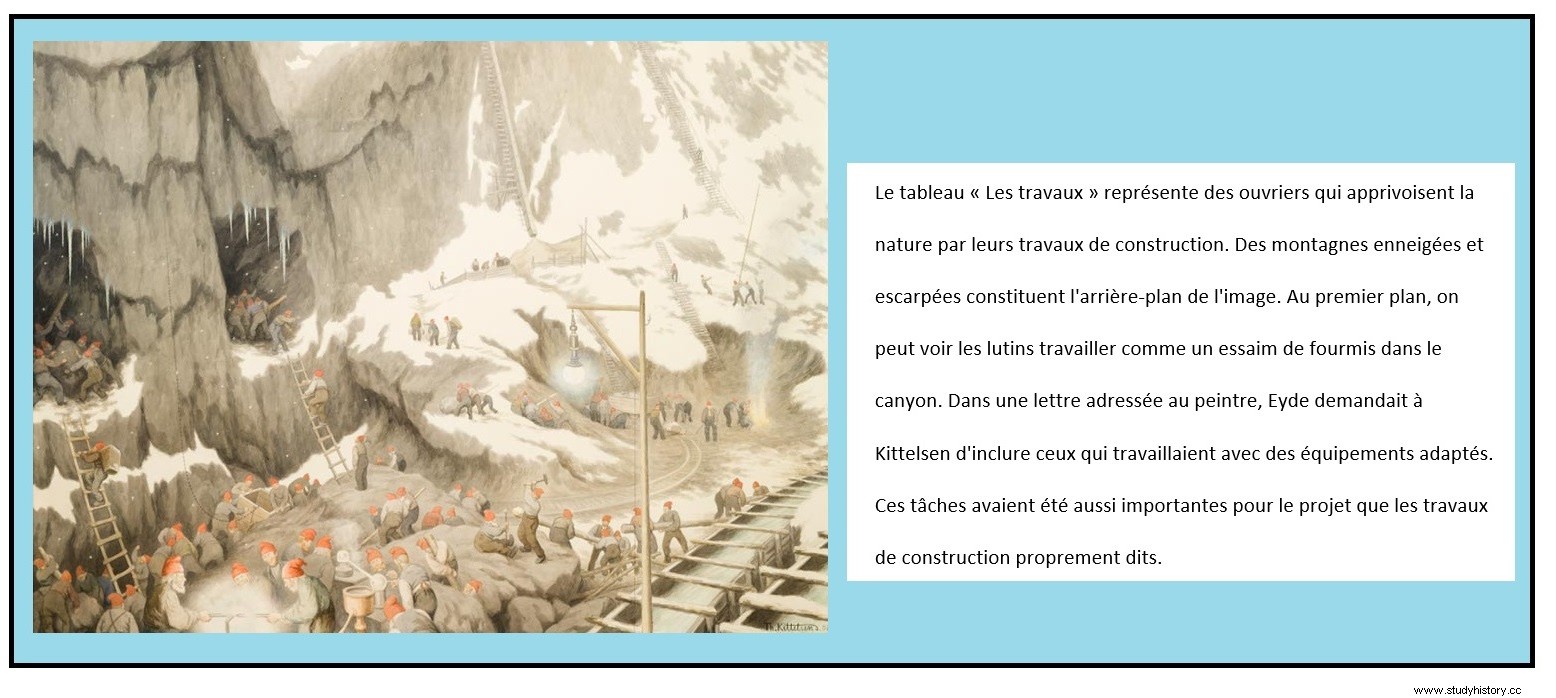

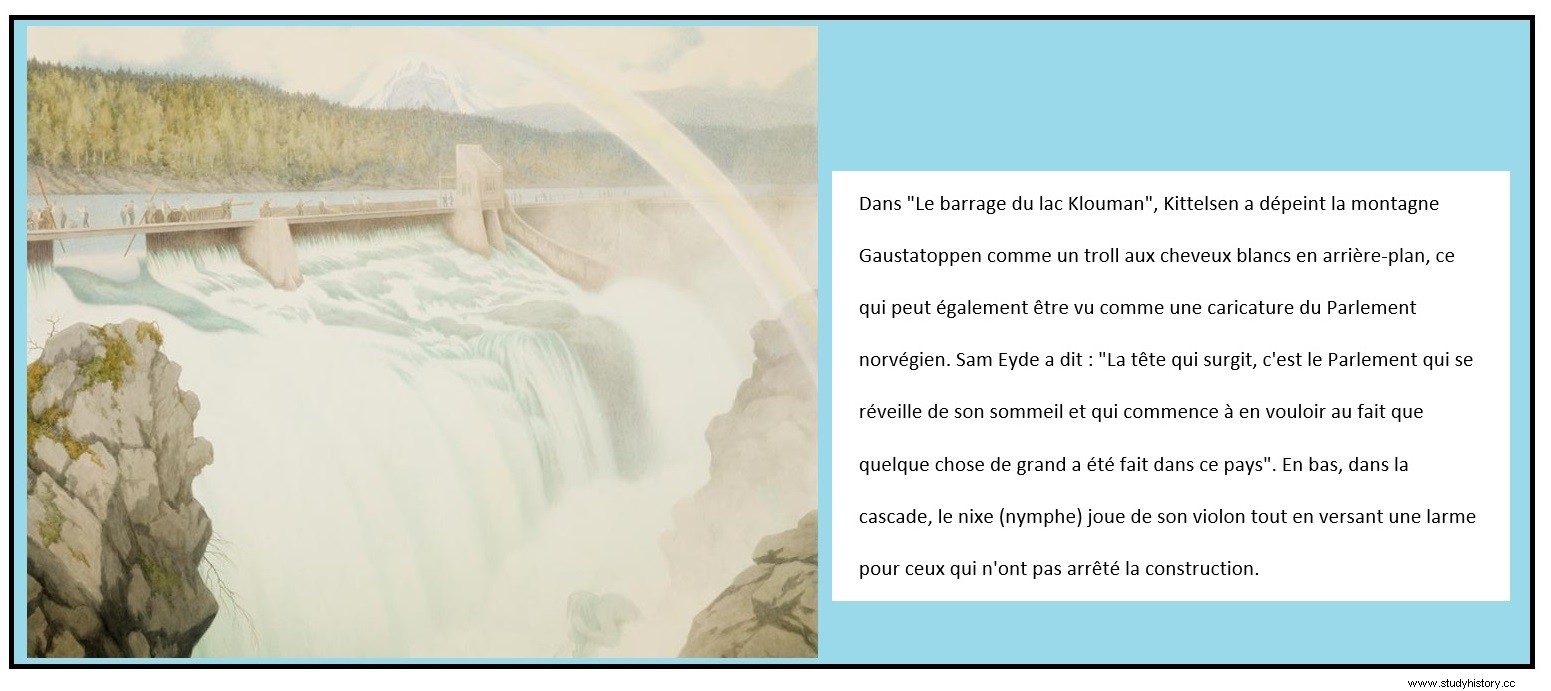

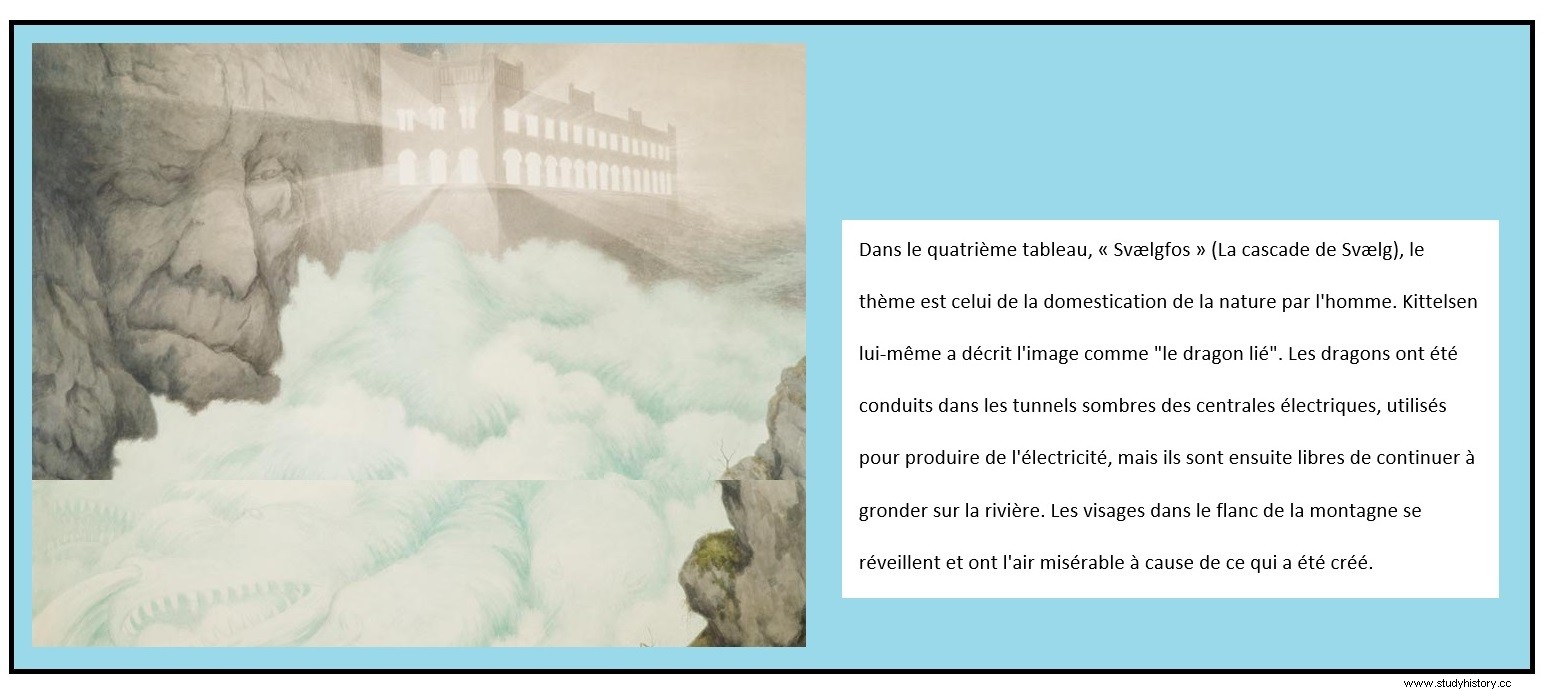

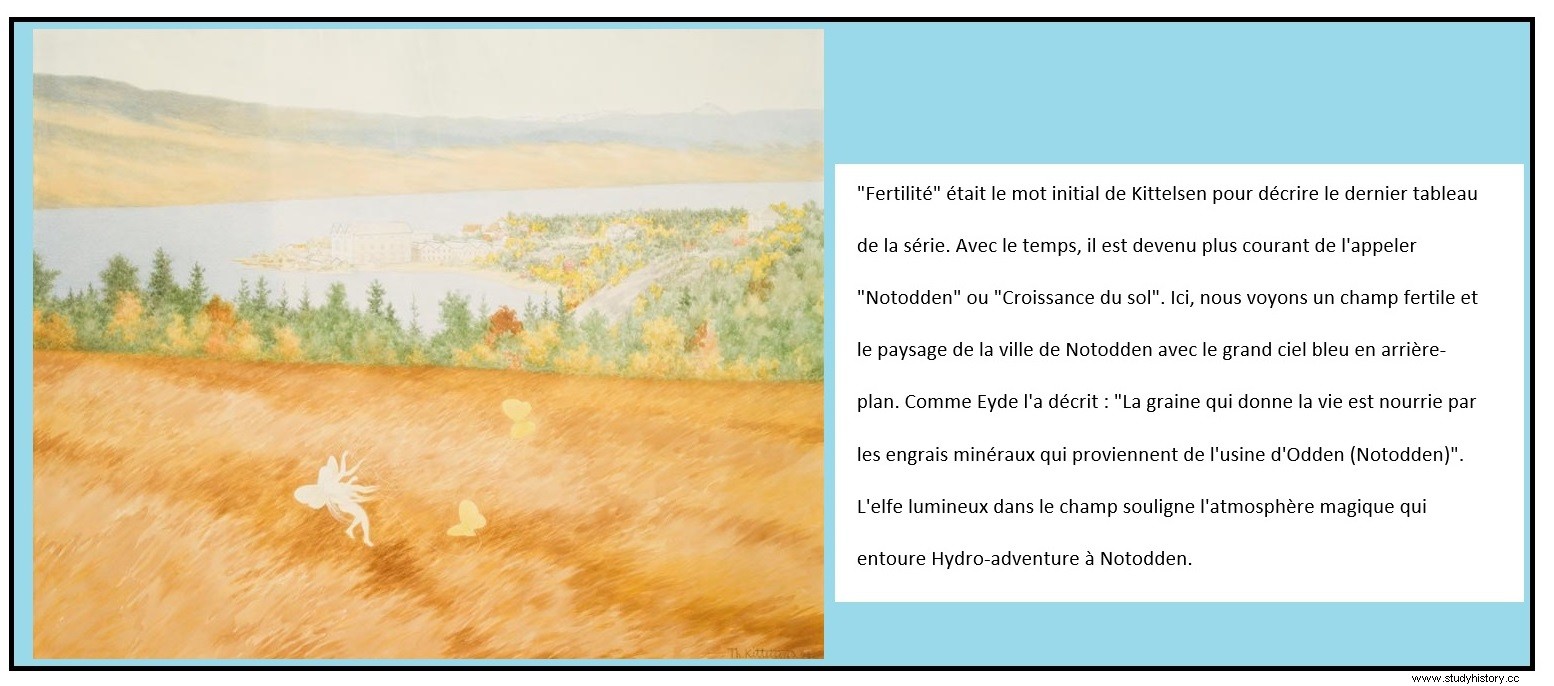

Let's go back for a moment to some of his work that was intimately linked to the events of his time. In 1907 and 1908 Theodor Kittelsen made watercolors of the development of the Svelgfoss power station. At the start of the 20th century, after the dissolution of the Sweden-Norway Union, Norwegian emigration to America took on worrying proportions. It was enough for the order of five watercolors by the engineer Samuel *Sam* Eyde, founder of Norsk Hydro and the first hydroelectric power station in the country.

Let's go back for a moment to some of his work that was intimately linked to the events of his time. In 1907 and 1908 Theodor Kittelsen made watercolors of the development of the Svelgfoss power station. At the start of the 20th century, after the dissolution of the Sweden-Norway Union, Norwegian emigration to America took on worrying proportions. It was enough for the order of five watercolors by the engineer Samuel *Sam* Eyde, founder of Norsk Hydro and the first hydroelectric power station in the country.

In fact, between the many artists of the 19th century who (re)imagined the tales and literary works of yesteryear and the emergence of a unity within a new nascent state, Kittelsen's talent thus combined folklore and technical innovation. A cynical modern eye might find this combination hazardous, futile or simply kitsch, but not for a man of that time. If today we can admire the works with a certain detachment, it is always useful to understand the springs of a nation-state that was built with the needs of its time and the resources at its disposal. The same string will still be used today, though perhaps not with the same finesse as Kittelsen's watercolours.

Sources and references

Illustrations used for this article:Förtrollade Norge, Norsk Trollvinter, Pesten, Svælgfoss.

https://www.visitnorway.com/listings/the-house-of-theodor-kittelsen/2029/

http://www.artnet.com/artists/theodor-kittelsen/

HEM