Work for free, from dawn to dusk. Life in miserable huts resembling dugouts. And complete lawlessness. We check whether Polish peasants really did not differ in any way from black slaves on American plantations. And was it really possible to do serfdom ... fifteen days a week.

I would not be a nobleman if the peasant were not a peasant; the wickedness of the peasant condition is ours - admitted the deposed king Stanisław Leszczyński without hesitation, and with these words he hit the heart of the entire economic and social system of feudal Poland.

The bondage of the peasant to the land, depriving him of almost all legal protection of the state, the possibility of having his life by the nobility made the peasants basically slaves, for whom poverty was complained even in other parts of Europe.

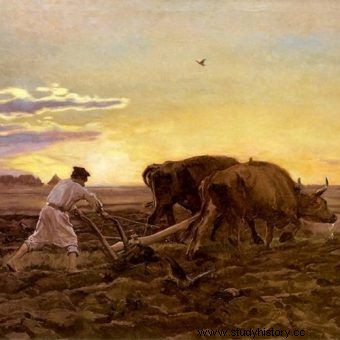

Although the serfdom functioning in Poland for centuries was a slave system, it does not mean that the peasants accepted their fate passively. The illustration shows the painting by Józef Chełmoński "Storks" (source:public domain).

But each system has its own vulnerabilities, and it was no different in this case. Even in the peak periods of serfdom and noble anarchy, even if his social position was humiliating, the fate of the peasant did not have to and did not necessarily have been bad . And they certainly have never been a group that is passive and humbly agreeing to the existing situation.

Serfdom - demonized duty

If you follow the letter of the law, it was tragic. Already in 1518, Sigismund I waived the right to settle peasants' complaints against landowners, and until 1768 the murder of a peasant by the master was completely unpunished . At the end of the 16th century, serfdom came from a semi-clandestine farm for 2-3 days and showed a growing tendency along with the good economic situation. Peasant poverty was eagerly described by enlightened thinkers, such as Stefan Garczyński:

A miserable peasant hut has a cage stuck like a tit, and there are about a lot of holes in it, the guest himself is almost at home, because he needs to do his role enough, that is, a haul send you away everyday; so some of his children from hunger, poverty and misery, the second from the cold and discomfort, the third from the stench and contagious diseases must die before time.

The Enlightenment reformers, however, usually showed quite a propensity to transfer ady. Without claiming that the fate of the peasant was enviable, it is worth looking at the calculations that Andrzej Wyczański made in this matter for the sixteenth century. They show that the income from the semi-horticultural farm was gradually increasing.

Calculated in Krakow prices, they amounted to:in the years 1501-1510 - PLN 4-6 (about six cubits of cloth and two thousand pieces of brick), 1521-1530 - PLN 6.5-10 (about ten cubits of cloth and five thousand pieces of brick). ). Wyczański adds to this amount the profits from the lease of still existing peasant groups, despite the expansion of the farm, empty fields.

Contrary to what we may think, in the 16th century the peasants also benefited from a good economic situation (source:public domain).

And it was not uncommon. On the basis of materials for the Korczyn starosty, he established that about 60-70 percent of the peasants participated in the leases who thus increased their income by 60 percent. Agreeing with Wyczański, J. Semkowski calculated that the income from these leases would allow the peasant to hire an additional 1.5 domestics on a semi-arable farm, which would significantly ease the obligation of serfdom.

"When the lord comes, he will plow well, when he leaves, as good ..."

Incidentally, the very duty of serfdom is also demonized. Without denying the fact that it was slavish use of free labor, of course, practice indicated that this free labor was not so easily exploited and from an economic point of view, it was more profitable for the nobility to treat the peasant humanly.

Working in the field of the feudal feudal peasants, as soon as they could avoid work (source:public domain).

In the 80s of the 15th century, an anonymous author wrote a poem on the card of the Latin dictionary, known today as "Satire on chytrych Kmieciów", which shows the reality of serfdom in an interesting way:

Cunning brute of the peasants,

There is a lot of messing about her hair.

When they are supposed to do your day,

They take a rest a lot.

And they are doing very hypocritically:

We'll come out at noon,

(…)

They haul sick belongings,

Willing to tickle all this day -

Because he intentionally agrees to do so,

That you will be born ill.

When you come, plow well

When he is gone, as good;

(…)

Even assuming that the poem was written by a noble, it seems quite obvious that the peasants did in fact used the method of passive resistance , dealing with your land just worse. But there have also been cases of quite active resistance.

During the rebellion of 1768, serf peasants, Cossacks and haidamaks murdered perhaps even 200,000 noblemen, clergy and Jews (author:Kozak Mamaj; source:public domain).

The most famous of the peasant rebellions, the so-called Koliyivshchyna of 1768, had a slightly broader context than just anti-nationalism - it happened during the Bar Confederation and you can see in it an element of Russia's political game.

Nevertheless, as a result of it, rebellious peasants killed from one hundred to two hundred thousand noblemen, Jews and priests . Smaller revolts broke out quite often, especially in the south-eastern outskirts of the country, ending for the rebels usually tragically, but making the nobility aware that, contrary to the letter of the law, they do not go unpunished.

Peasant asks for serfdom

Rebellions would not have been possible if the next element of the feudal system - the peasant's tethering to the land - were not a myth. Formally, from the end of the fifteenth century, one peasant son a year could leave the village, in practice the migrations of peasants continued without interruption until the end of serfdom.

It was facilitated by the nobles themselves, who massively used the so-called lounging, that is, previously agreed with the person concerned, "kidnapping" and settling on their own land on better terms.

Jan Rutkowski describes the cases of convergence of peasants in the 16th century as "completely common" and develops this idea also for the following centuries:

Absolute attachment to the ground was also out of the question in the 18th century. Although there are known cases of the return of subjects, however, according to the widespread opinion, the trials of the escaped subjects were often not even started, because either the fugitive could not be found, or the trial was not profitable.

Contrary to popular belief, many peasants fled to cities, where they became full-fledged townspeople (source:public domain).

Finally, it must be remembered that the peasants also escaped on their own , contrary to popular opinion and despite numerous bans, obtained city rights. In the years 1538-1607 in Biecz, they constituted 66.8 percent, in Old Warsaw and Chojnice in similar years - 46 percent. Others fled to the forests where they were part of the robbery bands from which, inter alia, the ranks of the later rebels recruited.

A painting by Józef Chełmoński entitled "Orka" from 1896

The low economic efficiency of serfdom and the peasant's attachment to the land began to be noticed in the times of the Enlightenment. From 1765, Andrzej Zamoyski abolished serfdom in the Bieżuń estate, Fr. Paweł Brzostowski in the Merecz estate in the Vilnius region, and a little later Stanisław Poniatowski in the Korsun estate.

However, an interesting thing is that the peasants, whether they were used to this form of work or overburdened with the rent imposed on them, asked Zamoyski to restore serfdom.

Despite these actions, this system lasted for nearly a hundred years and even Tadeusz Kościuszko, who in the Połaniecki Universal made a revolution anyway, granting the peasants personal freedom, did not change it. However, serfdom itself was only lifted by the invaders. The earliest, in 1811, it took place in the Prussian partition, in 1848 the coup took place in Austria, and the Kingdom of Poland had to wait with it until 1861. Question:who was waiting for it more - lords or subjects?

Despite the formal abolition of serfdom in the nineteenth century, Orawa and Spisz (in the Salamons and Jugenfeld estates and in some church estates) existed until the 1930s. a gelatin machine, which can be considered a form of serfdom. It was finally abolished by the Seym Act of March 20, 1931 on the liquidation of the Jelarski relations in Spisz.