The public education system in the Greek state of the 19th century. was founded during the time of the Othonian monarchy with a series of regency decrees (1833-1837). It was applied without serious structural changes for about a century. Essentially, it was a complete transplant of the Bavarian model. That is why its application in the Greek social reality, at least in the initial stages, was inevitably difficult.

It was generally organized in three tiers:

A. Elementary-Primary Education, i.e. the Primary School, in which children aged 5-6 were admitted. The dominant language was spoken Greek. Education was compulsory and free for boys and girls. Until the end of the 19th century, the four-year Primary School functioned mainly as a preparatory anteroom for Secondary Education, without essentially an independent purpose.

B. Secondary Education included two stages:

a) the three-grade Greek School (School), which covered the last two grades of today's Elementary School and the first grade of today's High School. Students who had completed the fourth grade of primary school were admitted to it. They ranged in age from 8-9 to 11-12 years old. Greek Schools were established in urban and semi-urban centers but also in communities.

b) the four-class Gymnasium, in which the graduates of the Greek School were admitted. Their age ranged from 12-13 to 18-19 years, without excluding older people. Gymnasiums were relatively few and only in urban centers. The official language of secondary education was Katharevusa. Access was typically not possible for girls.

G. Higher Education, i.e. the University of Athens (1837). Until 1927, high school graduates were freely admitted to it.

Entrance to the Greek School since 1867 is only through exams. In the Gymnasium entrance examinations were established from the beginning. Promotional and baccalaureate examinations until the 1880s had not received substantial state care.

The question of the imposition of educational fees on the students of the Greek School and Gymnasium concerned the State from the establishment of the Greek state until the last decade of the 19th century, when it was finally regulated.

The relevant decree of 1836 provided for a student registration fee of three drachmas for the Greek school and five drachmas for the Gymnasium. He had also established one (Greek) and three (Gymnasium) drachmas as the right of "proof of course completion".

It is not known if this law was ever enforced. I suppose that the general poverty of the population and the dominance of the ideology of the "enlightenment" of the genus at least until the middle of the century, with education being considered "the intellectual manna that nourished the hopeful people in their exile", acted as a deterrent.

Moreover, for the same reason, the payment of tuition fees to the University, which was provided for by its Regulations, was not implemented. However, during the period of the Trikoupi administration, in the context of the continuous deterioration of the fiscal figures, the tax riot could not but affect education as well.

With the tri-cup law AHKE,/ 1887 "on stamp fees" the amount of the fee imposed on public secondary education qualifications was adjusted as follows: One drachma for the indicative Greek School and Gymnasium, two drachmas for the Greek School diploma, five drachmas for the Gymnasium diploma. In 1887, therefore, the imposition of educational fees, in the form of a stamp, is limited to public qualifications produced before higher education institutions or other authority.

The seventh Trikoupi government, a little later, will put an end to this issue. In particular, he submitted to the Parliament a bill to adjust the educational fees to unaffordable levels for the lower classes. Students paid for registration, transfer, additional fee, stamp for the diploma and other qualifications.

In more detail, the BND/1892 law multiplies the fee for Secondary Education titles in relation to 1887. Furthermore, high fees for registration, exercises, etc. are defined. For example, registration at the Greek School for the first semester cost 20 drachmas and for the second semester 15 drachmas. The indicative fee of the same school increased from one drachma to five.

In comparison, just the registration and tuition for the Greek School required an expense equal to about half the salary of a teacher at the time . Also, at the end of the 19th century, a man's daily wage, usually casual, was around 2 drachmas.

During 1892 the students of the Greek Schools amounted to approximately 20,000, while those of the Gymnasiums only reached 5,000. With this given, the taxation of the former, according to Trikoupi's calculations, would yield half of the amount the state expected to collect from the specific proposal.

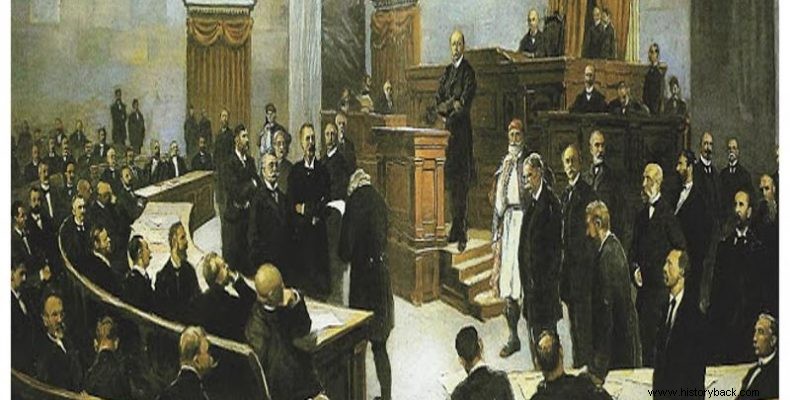

The parliamentary debate was intense. All in all, the small opposition demonstrated the unconstitutional, anti-national, plutocratic and lights-out nature of the bill. He gave special weight to the social inequality that was to be brought about by its application.

Theodoros Diligiannis, for example, criticized the imposition for the first time of registration and re-registration fees for the students of the Greek School. On the contrary, Sp. Stais, member of parliament from Kythera of the coalition, as the main argument for the passing of the bill unequivocally put forward the reduction of "the number of students in Gymnasiums and Greek schools".

There were students, he argued, who were enrolled for the fourth consecutive year in the same class and who would be forced to discontinue their studies. No parent will now be so stupid, after the bill was voted down, as to insist on paying fees "for a child unfit for learning", which for the buyer was "the pollution of the whole class".

In December 1892, the same Trikoupi government will submit a new bill to the Parliament for the extension of the education fees and stamp fees defined under the BND/1892 law. The regulation concerned the students of the publicly supported High Schools that were also subsidized by the public and the certificates and diplomas of the private schools of those assimilated to the public ones in the test of the students.

The next issue of interpretation that arose and related to Gytheio High School is a presumption of the draft law in question. Specifically, on the occasion of a question from a Messinian member of parliament, a long debate was held in the Parliament regarding whether the law on the extension of fees should also be applied to Gytheio High School, birthplace of the Minister of Education K. Kosonakou.

Among other things, the minister mentioned that the Gytheio High School was supported by a grant from the port fund amounting to 16,000 drachmas and by a contribution of 8,000 drachmas from the Municipality. Therefore, according to his claim, the high school principal should not have collected fees from the students. However, it seems that the interpretation of the latter and the Prefect of Laconia who had issued the relevant circular was the opposite.

However, the proposed discriminatory attitude of the Minister of Education, when according to his previous statement the measure concerned all Gymnasiums of this category, without exception, is cause for concern. The payment of the fees in combination with the purchase of the books acted as a deterrent for the education of a significant part of the children who belonged to financially weak families. 16,000 students, according to Theodoros Diligiannis, were forced to leave school classes in 1894, due to hardship.

The fees will be significantly reduced, but the government of Diligiannis will not abolish them after 1895. Justifying his choice, he stated in the Parliament:"I do not think that the educational fees were not effective, but I think that the time at which they were imposed It was very appropriate, because we were on the eve of bankruptcy, the taxes had put all the productive work in the country to the fore, they had exhausted all the savings, so the people did not all have the necessary money to pay these taxes".

Criticizing the government at the time, Diligiannis will mention that the primary goal of imposing education fees was to prevent "the untouchables" from advancing to the higher levels and guiding them to "life projects", but without at the same time taking care to prepare them, through Primary Education, for this purpose. Primary Education had to "contain all this knowledge, which the ordinary worker, the ordinary farmer is required to have".

The relevant law, in addition, provided that the revenue from the fees would not be deposited in the public treasury to cover budget deficits, but would be allocated for the construction of school buildings and the improvement of the school infrastructure. Therefore, for the first time, their utilization in favor of education was legally guaranteed.

In the above legislations, despite the suggestions from MPs, there were no provisions for partial or total exemption for special categories of students. In the following century, however, a humanitarian provision appears with ministerial decisions. Thus, interwar refugee children and second siblings are enrolled incompletely.

Furthermore, needy students - at a rate of 10% of the registered students - are exempted from tuition fees by decision of the teachers' association. There was even a 50% discount for teachers' children.

In short, we find a broad political consensus on the payment of educational fees, which will remain fluctuating until the middle of the 20th century. Determining factors of their preservation were the inability to provide free education to the growing student population, the need to orient the youth in practical directions and channeling the corresponding amounts exclusively to education.

Furthermore, the Greek secondary education system since the second half of the 19th century tends to exclude a significant part of the youth. In other words, education incorporates a strong class dimension with the stated or tacit consent of the majority of political parties.

As an institutional mechanism of social selection, the educational fees can be characterized as well as the exams, which since the 1880s with legislative regulation have become exhaustive, extremely strict and meticulous. Factors, in addition, that contributed to the exclusion were the geographical distance from the school, the "cultural capital" of the student's family, the size of the residence settlement, etc.

INDICATIVE BIBLIOGRAPHY

> Katsikas, C. &Therianos, K. (2004) "History of modern Greek education. From the foundation of the Greek state to 2004", Athens:Savvalas.

>Koudounis, V. "school performance and "cultural capital". The case of the four-class Gymnasium for boys in Sparta in the interwar period (1919-1929)", in press.

>Mylonas, Th. (2004) "Sociology of Greek Education", Athens:Guteberg.

>Skoura, L. (2013) "The imposition of tuition fees in public general and university education (1887-1895):educational, economic and socio-political dimensions" in >"THEMES IN THE HISTORY OF EDUCATION", issue 11, pp. 129-156, Athens:ELEI

>Tsoukalas, K. (1987) “Addiction and reproduction. The social role of educational mechanisms in Greece (1830-1922)", Athens:Foundation.