A new edition has appeared, revised and updated, from Eric Cline's book, 1177 BC:The Year Civilization Collapsed . I bought the slightly (!) cheaper e-book version. The new edition is 40 more pages long, but most of the changes are generally subtle, especially in the first four chapters. For example, the final section of chapter 1 has a different title, and some additional details and explanations have been added here and there (for example, in the section on the Trojan War in chapter 3).

The most important changes affect chapter 5:it has been divided into two chapters, 5 and 6, and some of the sections have been reordered. Now the new chapter 5 ends with the section on climate change, the text that has been reworked in chapter 6 has been partially rewritten and new paragraphs have been added. But in general, the changes and additions are relatively minor:therefore “revised and updated” instead of a full-fledged "second edition."

1177 a. C. provides a good overview of the many questions surrounding the events that marked the conclusion of the Final Bronze , but I have always found the treatment of the subject somewhat unsatisfactory for reasons that I am only now beginning to make clear.

And despite the criticisms that I will make of the book in this article, I certainly want to make it clear that 1177 a. C. still offers the best treatment of the subject that is currently available. If you haven't read it yet, I recommend you do. And perhaps some of the criticisms that I present here can be taken into account for a future revision of the book.

In any case, 1177 a. C. it has been constantly promoted as something very “relevant” for the modern age; a book from which lessons can be drawn. In the new preface, Cline writes (p. XVII):

The Black Lives Matter protests are not mentioned here , nor the growing disparities between rich and poor; these omissions are not accidental, as we will see later.

At the end of the preface, Cline writes that (p. XIX):

But what should we pay attention to? In fact, who is the “we” referred to here? Can ordinary people do more than live as well as they can, vote for politicians who seem out to make the world a better place, and take part in demonstrations when political leadership fails?

The Late Bronze Collapse:A Perfect Storm

One of the things that struck me about 1177 BC. C. , when I was rereading parts of the first edition, and that is also true for the new edition, is how little human action seems to play a part in the events that mark the end of the Bronze Age. The fifth chapter, "A 'Perfect Storm' of Calamities?" analyzes different elements that may have contributed to the end of the Bronze Age.

These “calamities” include earthquakes, climate change, drought and famine, invaders from areas outside the territories of the great kingdoms, and the “collapse” of international trade, the decentralization and the “rise” of the “private trader”. The sections dealing with “system collapse” and complexity theory have been moved to a new sixth chapter in the revised edition, and that makes more sense structurally, even if I don't think mapping historical events and processes onto abstract models really explains anything.

It is after the discussion of systems theory that, in both the original version of the book (chapter 5) and this new one (chapter 6), Cline finally settles on all of the above topics as reasons for the “collapse” . He suggests that complexity theory – a way of modeling and analyzing complex systems (in this case, societies), with a focus on interaction and feedback loops – provides the answer to understanding what happened at the end of the Age of Bronze:A conveniently sterile solution to a complex problem.

With all the talk about systems theory and its derivative, complexity theory, I was reminded of what I read in the important book by Michael Shanks and Christopher Tilley, Re-Constructing Archaeology (2nd edition, 1992). They deal with systems theory on pages 52-53 (emphasis theirs) and point out that:

Shanks and Tilley's particularly chilling conclusion on systems theory is that (p. 53; with my emphasis in bold):

Now, within the fifth chapter of Cline's book there is a very short section, consisting of three paragraphs, with the title “Internal Rebellion” (pp. 147-148 in the original edition; in the new edition, this section has not changed). Blink and you'll miss it. Cline writes that “some scholars” (p. 147) suggest that such “revolts” could have been triggered by a number of factors, including the aforementioned famines, caused by a series of natural disasters, or even the “cut off of power.” international trade routes”.

Cline writes that “each and every one of which could have dramatically impacted the economy in the affected areas and led dissatisfied peasants or lower classes to revolt against the ruling class” ( pp. 147-148). But while "peasants" may have caused some of the destruction, Cline suggests that much of it "frankly, there's no way of knowing whether rebellious peasants were responsible" (p. 148).

Cline adds that many “civilizations – itself a problematic and value-laden term that I think are best avoided – have successfully survived internal rebellions and, have often flourished under a new regime” (p. 148). My immediate response would be that if a rebellion caused a "regime" change, how could this not be significant? In reading an earlier draft of this article, Joshua Hall correctly pointed out to me that regime change need not affect society at large , or indeed impact existing networks of social power:same wine, different bottles. Still, I would have liked to see Cline expand a bit on this point.

The anarchist theory offers a different way of looking at things. Anarchist anthropology has been gaining momentum for at least a few decades, and has since found its way into archaeology, too. It is still new and/or niche enough that, for example, the most recent edition of Archaeological Theory:An Introduction by Matthew Johnson, published in 2019, don't mention it even once.

The anarchist theory itself has no main proponent, and it is perhaps difficult to speak of a unified theory at all; it is more properly a series of ideas. A useful introduction is Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology (2004), by David Graeber, describing some of the ways in which anarchist theory is useful. There is also this "Community Manifesto", which outlines the main characteristics of what an anarchist archeology could be.

If I were to point to one aspect of anarchist theory that is particularly helpful in understanding the late Bronze Age, it would be the questioning hierarchy approach . And at this point I must emphasize that anarchist theory is not only about questioning our interpretations about the past, but also about the discipline itself and the world in general around us. It is ideal as a starting point for those of us who not only want to study and understand change, but also create changes in ourselves.

Hierarchy and patriarchy in the collapse of the Late Bronze Age

But back to Final Bronze. A key characteristic of the kingdoms that existed then is that they were all hierarchical and patriarchal . In a sense, they were ordered:the rich and powerful were at the top, and the poor and oppressed at the bottom. Within a hierarchical system, the "peasants," to use Cline's term, were apparently of little importance to the people at the top.

Cline ignores the social dimensions of “collapse”. However, it is those social dimensions that I think are worth examining in much more detail. After all, one of the key discussions to be had in our modern world is how we are going to resolve the vast wealth disparities that currently exist. For example, Jeff Bezos is stepping back from his role as Amazon CEO . He is the richest man in the world, currently worth close to $200 billion, an amount of money so grotesque it is unfathomable. The pandemic may have affected millions of people negatively, but the world's richest billionaires, including Bezos, have only seen their wealth increase.

Currently, an example circulating on social media and various news websites shows how rich Bezos is:if he had given each of his 879,000 Amazon employees a $105,000 bonus at the start of the pandemic, you would be as rich today as you were at the beginning of last year. Needless to say, Bezos hasn't engaged in this level of altruism, content instead to have Amazon's lower echelon workers peeing in jars so as not to hurt their "efficiency," and scrambling to make ends meet. month with the minimum wage.

Could similar disparities have fueled the vaunted “collapse” of the Late Bronze kingdoms? I'm thinking of the previous occupant of the White House, literally fenced off to protect him and his cronies from angry protesters outside. As someone who has studied ancient fortifications, one of the points I usually make an effort to make, like here or here, is that walls aren't just meant to defend something from outside threats.

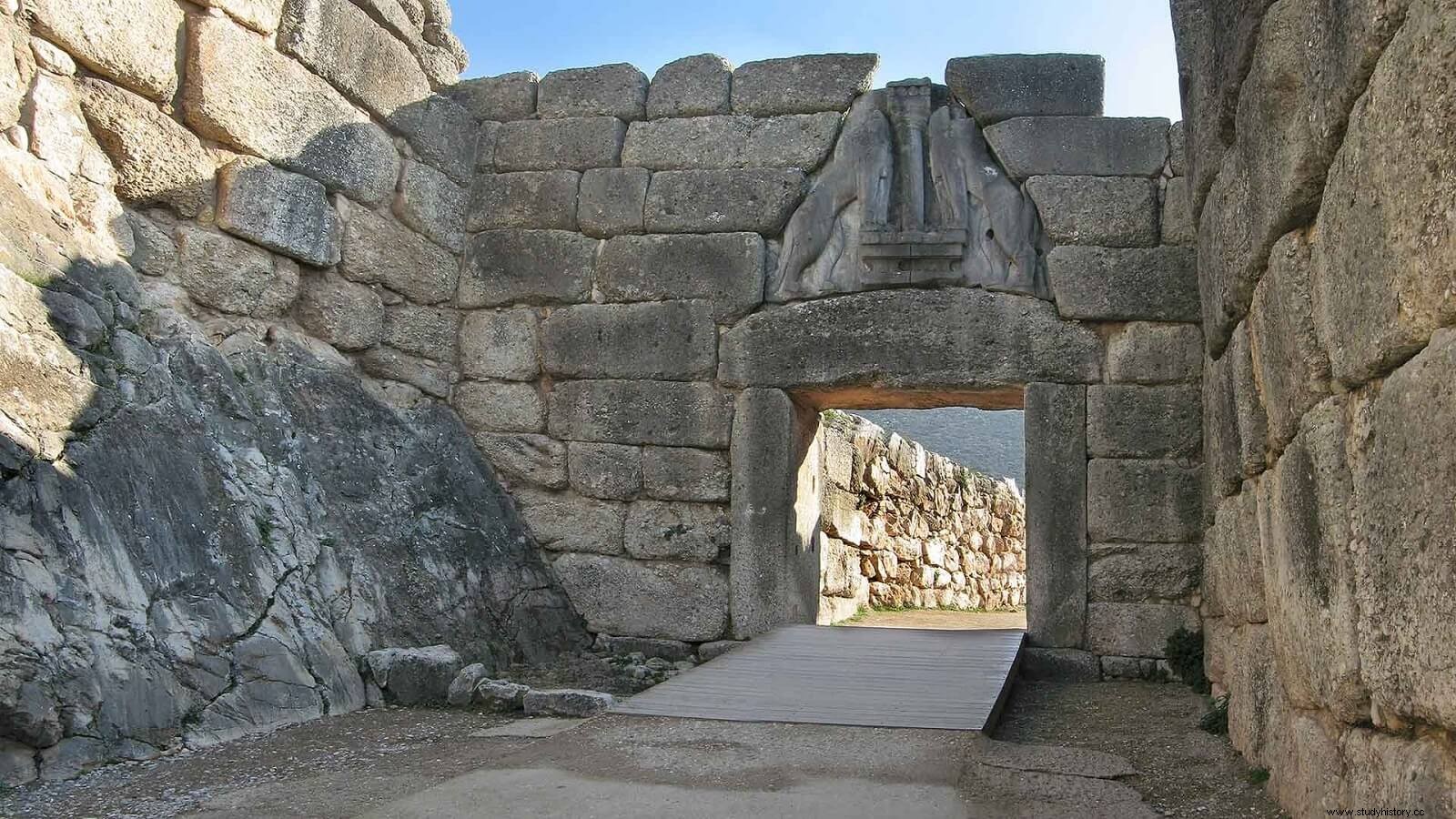

The huge fortifications that defended Mycenae , for example, were modified at the end of the 13th century BC. C. to encompass a larger area of the citadel:the walls were extended to include the Circle of Tombs A, the Gate of the Lions was built and a water supply was secured within the Mycenaean citadel area. The reasons offered to explain this massive building programme, undertaken perhaps a few decades before the citadel was destroyed, are varied, ranging from prestige (e.g. status rivalry with other fortified centers in the Argolis) to fear of attack.

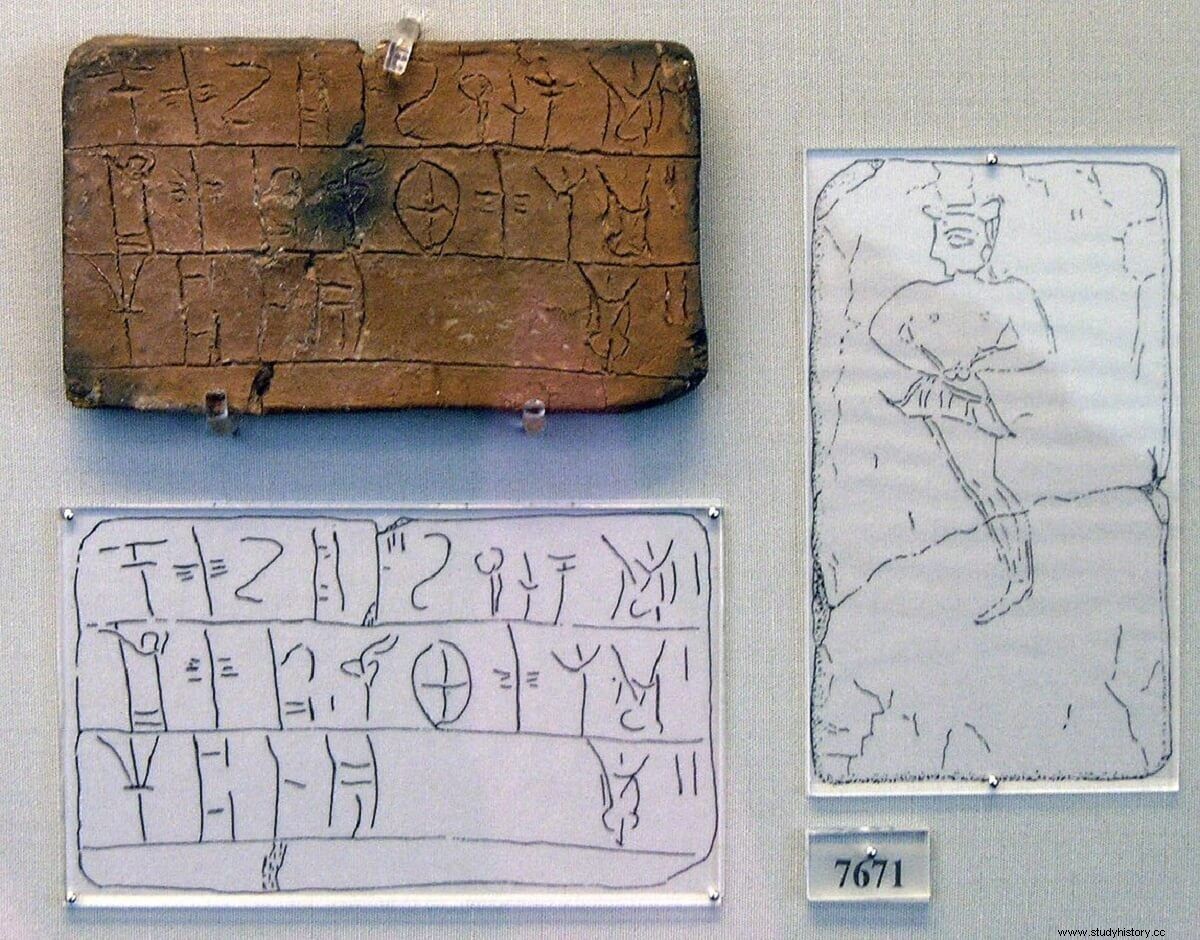

But at this point it is good to point out that the citadel did not house the vast majority of the population of Mycenae. It was the residence of the ruler –wanax in the Linear B tables – And his family and his dependents. What if the massive fortifications were not built out of vanity or fear of external enemies, but mainly to secure the position of the local ruler? What if the “peasants” of Mycenae had had enough of having to live off scraps while the wanax throwing ever more elaborate banquets up there on his glittering hill?

I don't think there is a way to know if this was the case or not, because the lower city of Mycenae, where most of the people lived, has not yet been extensively excavated . In fact, none of the low cities around the major Bronze Age centers, in the Aegean at least, have been the subject of archaeological investigation until relatively recently. This highlights another problem:the interest of modern scholars, often operating in a more or less secure environment, in understanding the upper echelons of society rather than the lower ones. Who cares about the “peasants”?

In fact, most scholars, consciously or not, assume that an orderly, hierarchical society is the only true way for humans to prosper. Therefore, when the Late Bronze Age kingdoms “collapse” the result is something undesirable:a “Dark Age” , in the pejorative sense of the term, in which the glorious kingdoms and empires of a bygone age have given way to a host of small communities that do not produce the frescoes, glittering palaces, and intricately wrought jewelry that look so good on photographs and book covers.

In the introduction to his Geometric Greece, 900-700 BC (2nd edition, 2003), Coldstream writes (p. XXII):

Jonathan Hall, in his History of the Archaic Greek World (2nd edition 2014), writes of the Dark Ages that (p. 60):

But what about the people who lived through this experience? What about the people who lived in these supposedly isolated, introverted and unstable communities in mainland Greece and elsewhere? Were they as miserable as modern scholarship suggests? In other words:can people only be expected to prosper when they are part of large, hierarchical societies with extensive business networks? Is this, to put it another way, a defense of disparities in wealth, power, and social status?

Using such value-laden terminology to describe historical situations does not help promote understanding. The inherent question I want to ask is is the disintegration of a hierarchical society necessarily a bad thing . Would a world in which the disparities between rich and poor are drastically reduced, possibly even eliminated, really be as miserable as modern scholarship suggests after the end of the Bronze Age or after the demise of the Roman Empire in the West? Q>

Anarchy is often interpreted in the negative sense of “chaos”, but that is not the true meaning of the word. Anarchy comes from the Greek anarchos , “have no ruler” . This does not mean that an anarchist society is rudderless; it simply rejects the notion of a fixed hierarchy. Experts still wanted; informal leadership may still be a feature (for example, entrusting an experienced builder to build something). But an anarchist society is organized on the principles of free association.

The societies that emerged after the destruction and disappearance of the hierarchical kingdoms of the Late Bronze Age were smaller. They were different. Undoubtedly, in many respects, they were fairer. The "peasants" no longer had to bow to a ruler who lived behind the mighty walls of his fortress on the glittering hill. Of course, the ruler who was deposed, and presumably killed during the riots, may have had a different opinion.

Indeed, for the common people, who never had much to lose in the first place, not much could have changed with the disintegration of the kingdoms. After all, these people were not the beneficiaries of the predatory systems that the upper echelons of these kingdoms exploited to enrich themselves. They didn't have ivory thrones or pet monkeys. All they tried to do was make ends meet.

Scholars before the collapse of the Late Bronze

In my opinion, this is where possible lessons can be learned from the “collapse” at the conclusion of the Final Bronze. Cline and most scholars who study the Late Bronze term see chaos and destruction, a disintegration of the social order. Cline is used to living in a strictly hierarchical world, going so far as to introduce scholars to his book in ways that underscore established hierarchies.

This is a sentence from p. 161 of the original edition of 1177 BC :

The way Renfrew is presented here is meant to awe us. He is from the University of Cambridge, considered a prestigious institution. He is also "one of the most respected scholars." It's an appeal to authority, a form of argument, a rhetorical trick in essence, which I was taught my freshman year in college to avoid at all costs. The excuse may be that the book is also written to appeal to the general public, who may not know who this Professor Renfrew is. But this does little to mitigate the argument. Perhaps things will get worse in the new edition:the new chapter 6 now starts with this statement!

If there is one lesson to be learned from the end of the Bronze Age, it is that we must seek out those who have the most to lose. In our modern world, young people suffer from relatively high levels of unemployment; they earn less than their parents and it is increasingly unlikely that they will ever be able to “own” (ie, mortgage) a home or save significant amounts of money. After the financial crash of 2008 and the pandemic that began in 2020 and is still continuing, much of modern society – the “have nots” – has little or nothing to lose if current hierarchies – which primarily benefit the “haves” "- they decompose. In fact, they have everything to gain.

The gap between rich and poor is continually increasing, not only within societies, but also between them. Current problems with the supply of the COVID-19 vaccine are an example:the richest countries are asking for more than they need, to the detriment of the poorest countries. When Madonna appeared in a video to proclaim from her bathtub that the virus was "the great equalizer" and that we are all equal now, people rightly scoffed at making this claim:the virus, like all things, does not affect everyone. people the same way.

Collapse or transformation of civilization?

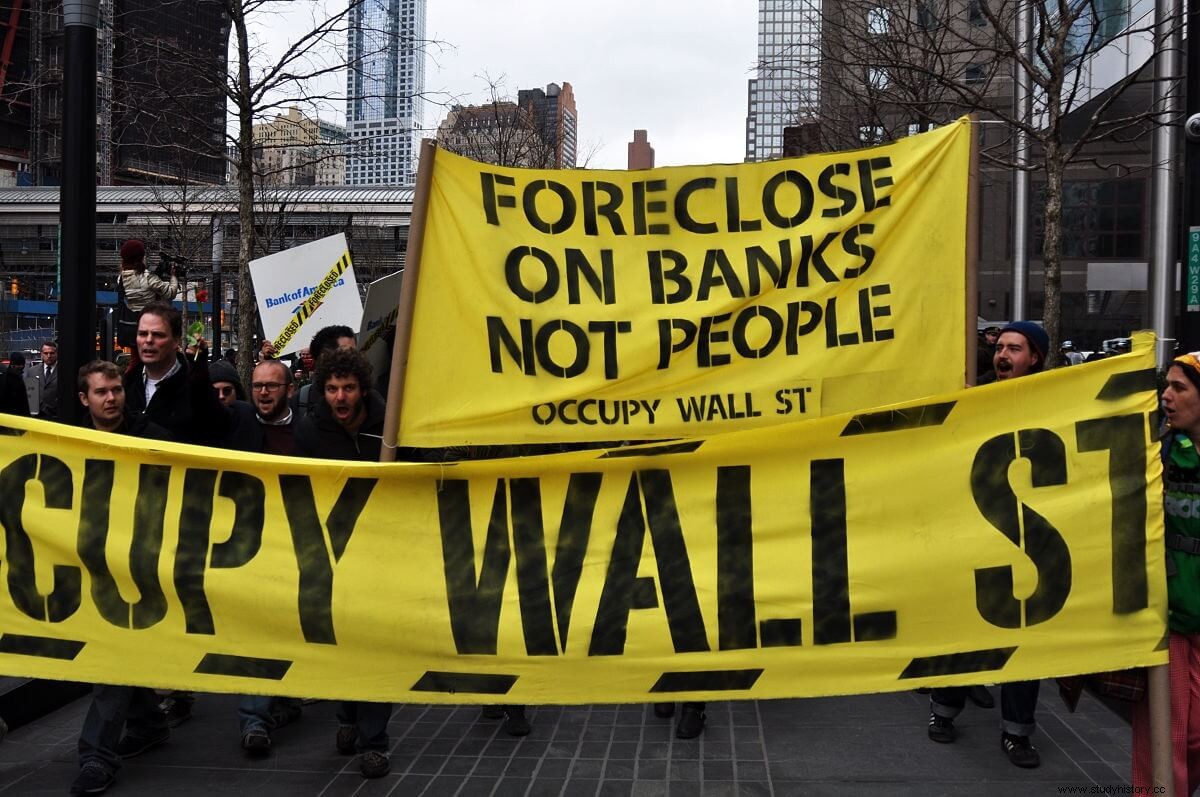

There have been many movements in the last two decades that show that society is under severe stress. The Occupy Wall Street demonstrations they erupted to protest wealth inequality. The Black Lives Matter protests they were seeking racial justice, which also requires socioeconomic equality.

But unfortunately the change itself is very slow. We see opportunistic politicians fanning the fires of hate in an attempt to ensure that the anger of ordinary people is directed at each other, at foreigners and refugees, rather than at the wealthy elites who exploit the system for all its worth.

Climate change, military and political disinformation, trade embargoes, international intrigues, migrations, pestilence:these can all be contributing factors to the “collapse” of hierarchical societies. But I would say that the fundamental cause is social. It is human action, or indeed inaction, that causes the "collapse" of hierarchical societies. And maybe "collapse" is the wrong word to use here; perhaps “transformation” is the more appropriate neutral term.

The destruction of kingdoms and empires at the end of the Bronze Age may have been dramatic, but not necessarily bad. Cline himself suggests that it may have been necessary to pave the way for new city-states and the cultures of Athens and Sparta.

“Finally – he writes (p. 176) – new developments and innovative ideas arose from them, such as the alphabet, monotheistic religion and, finally, democracy. Sometimes it takes a large-scale wildfire to help renew an old-growth forest ecosystem and allow it to thrive again.” The Dark Ages are transformative only in the sense that it hastens and ushers in a new hierarchical order.

But the problem is that Eric Cline's train of thought here is clearly teleological:the collapse happened and from the supposed ashes new societies arose to take the place of the old ones. In my opinion, he begs the question:for human beings to “thrive”, do we need to function as part of a hierarchical society? Or is there a better way?

Certainly, the Greeks experimented with different forms of society, but in the process they created other forms of hierarchical societies that relied on slavery to such an extent that to say that these were improvements goes without saying. too far. The marble temples of classical Athens were built with money extorted from suspected “allies” of Athens, and silver mined by slaves who literally worked themselves to death. How different should we view such systems from the exploitative kingdoms of the Late Bronze Age?

Bronze Age teachings for today

1177 BC provides warnings, but no solutions. This is because the book doesn't seem interested in understanding possible social problems. Therefore, there are no references to movements seeking social justice, nor Occupy Wall Street , nor Black Lives Matter (The new edition still contains the statement in the epilogue, on p. 175 of the original edition, that some people warned that “something similar” to the Bronze Age collapse would happen “if banking institutions with a global reach were not rescued immediately!”)

Throughout 1177 BC , it is obvious that hierarchical societies are the ideal; the Dark Ages are to be abhorred. The implicit solution is that political leaders must seek to maintain a rather dark, almost sterile, "balance" that ensures that the "peasants" do not overly alter the status quo . As Shanks and Tilley put it in the passage quoted above, such a position "implicitly justifies oppression."

To face the “collapse”, we must strive to build a better world. That starts with understanding that the playing field is not level and that we must all work together. If the history of the Final Bronze Age teaches us anything, it is that wealth cannot be hoarded by a few to the detriment of many. That all human beings should be treated equally and fairly. In other words, a better world is one that is socially equitable and ecologically sustainable.

Bibliography

- Cline, E. H. (2021):1177 B.C.:The Year Civilization Collapsed:Revised and Updated . Princeton University Press.

- Coldstream, J.N. (2003):Geometric Greece 900-700 BC . Routledge.

- Graeber, D. (2004):Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology . Prickly Paradigm Press.

- Hall, J. (2013):A History of the Archaic Greek World, ca. 1200-479 BCE . Wiley-Blackwell.

- Johnson, M. (2019):Archaeological Theory:An Introduction . Wiley-Blackwell.

- Shanks, M. &Tilley, C. (1992):Re-constructing Archaeology:Theory and Practice . Routledge.

Original article in Ancient World Magazine .