Salt has been with Man almost since the beginning of time. Its usefulness as a condiment and preservative extends to other uses that were applied to it historically, both therapeutic and ritual, so it is not surprising that in many corners of the world where it was not abundant, it was also used as currency -such as inland Africa-. Now, of all the extra applications that it has had, probably the most curious was the one in which it was spilled on the ground of cursed places in order to purify or denigrate them forever; what was called salting the earth.

Salt has been obtained since prehistory, either by excavation of deposits, or by evaporation of seawater in salt flats, so salting the soil is a custom that dates back many millennia. We find it already in ancient times in the Near East, where its association with desolation and the purging of ill-considered sites was common. Hittite and Assyrian documentary references are preserved that speak of salt as a purifying element of destroyed cities, although the reason for this element is not clear.

In fact, it was often not salt itself - that is, sodium chloride crystals - that was used, but other minerals or even vegetables associated with it. This is the case of thekudimmu , with which the prehitite king Anitta covered Hattusa, or the sahlu , used by Ashurbanipal in Elam. Both are denominations for indeterminate plants, the weeds that we now call weeds generically and that usually grow in abandoned or devastated places. Because, as seems obvious, it is practically impossible for the entire surface to be covered with salt, not only because of the difficulty of gathering such an amount but also because it was too valuable an element to be wasted in this way. We'll look at it in more detail later.

In any case, we do not know exactly what the salting the land consisted of.; beyond the statement, we do not know what the process was like, although historians and archaeologists believe that it was surely something more symbolic than real. Salt can be toxic to crops, hence its choice in these cases, but no evidence has ever been found that its application was carried out to the letter in large areas of land. It is possible, and so some scholars point out, that it was part of the Herem, the sacred extermination practiced by the Hebrews following the model of other Mesopotamian cultures (the assakum of Mari, for example, or the Moabite ritual warfare).

The Herem was clothed in religiosity but underlying it was nothing more than a way to dominate and control the surrounding peoples, numerically superior and idolatrous (they were supposed descendants of Ham, the wayward son of Noah), so that the cyclical punitive expeditions against them they kept them at bay and separated to avoid spiritual contamination. The massacres recounted in Deuteronomy they attest to the matter but in reality it was not exclusive to Israel; the kryptheia Spartan warfare (raids carried out by young warriors against the helots every time new ephors were named) and the Mesoamerican flower wars (contests arranged to provide themselves with sacrificial prisoners) probably had a similar meaning, according to experts.

We said that, in this context of tension, salt is mentioned in several ancient sources and we made reference to The Bible , where salt fields and cities often appear. One of the texts that make up the Old Testament , the Book of Judges , which is also part of the Tanaj Hebrew and tells the sacred story between the death of Joshua and the birth of Samuel (that is, when the Jewish people abandoned their nomadism), narrates how the judge Abimelech, son of Gideon, eliminated all his brothers to proclaim himself king and that led to the Canaanite city of Shechem to rebel; the monarch crushed the insurrection, razed the city and had it covered with salt.

The importance of salt in that historical period and that geographical latitude is not accidental. There is the Dead Sea, a huge salt lake 76 kilometers long by 16 wide with a salinity level of 30%. From a long line of cliffs, that of Jebel Usdum, the Hebrews extracted salt by evaporation and the product became so important that the Second Book of Chronicles states: "Have you forgotten that the Lord, the God of Israel, gave David the kingdom over all Israel in perpetuity and that it was countersigned with him and his descendants by a covenant of salt?" A salt pact was the fancy way of saying inviolable, hence it was used to symbolically seal deals, like a handshake.

It should also be remembered that newborns had salt rubbed on their skin and that, in the Genesis , God punishes the disobedience of Lot's wife by transforming her into a pillar of salt. But it is in Leviticus and in Ezekiel where sodium chloride appears directly associated with religious ceremonies:«And you shall season with salt every offering that you present, and you shall never lack from your offering the salt of the covenant of your God; you shall offer salt in every offering of yours.”

Now, like coins, salt had two sides and if one was used for the positive, the other was destined for the negative. Books such as the Psalms, Job, Jeremiah and Judges they refer to the practice of salting the land of defeated cities to manifest their cursed character, reprove their population and purify them before God. If a city broke the pact of friendship sealed with salt, it was only fair that it be that product that also cleansed its infamy. And we don't just find references in the Old Testament; in the New , the evangelist Mark cites the use of salt to apply to prisoners, for example.

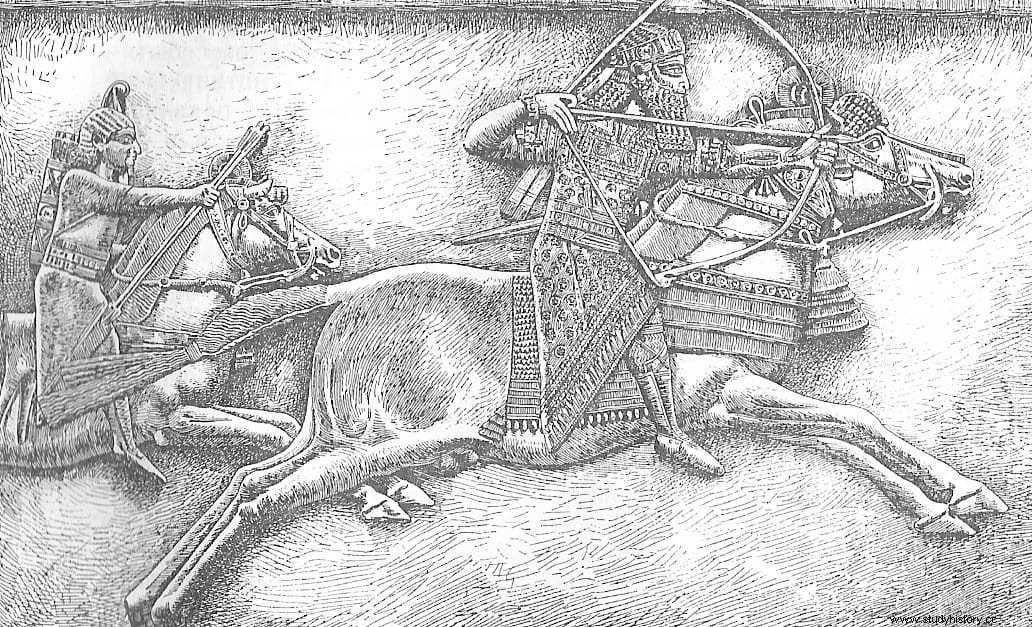

Apart from these biblical episodes, many cities in the Near East suffered this pain when they fell into the hands of their enemies. For example Susa, which was the capital of the Persian Empire after its conquest by Cyrus the Great and that it ended up salty after the Assyrian Asurbarnipal seized it in 647 BC, who wrote on a tablet: «I destroyed the ziggurat of Susa. I crushed the shiny copper horns. I reduced the temples of Elam to nothing; their gods and goddesses, I cast them to the wind. The tombs of their kings, ancient and recent, I devastated, exposed them to the sun, and carried their bones to the land of Ashur. I devastated the provinces of Elam, and in their lands I planted salt."

Hattusa, capital of the Hittite empire; Irridu, a Mesopotamian enclave that ended up under Mitanic rule until the Assyrians took it again, razed and salted it; Arinna, another Hittite city of uncertain location; Taite, capital of the kingdom of Mitanni that has not been able to be located geographically either. As can be seen, the Assyrians had a special predilection for the custom of salting the land of those places that refused to surrender to their armies, not to mention the atrocities they used to practice on their captured defenders.

The Romans, always so practical in matters of war and devastation, would have adopted that habit, just as they did with the crucifixion. However, you have to be careful with the quotes because they are often later and based on legends, rather than reality. Thus, the story that Titus had Jerusalem covered with salt after successfully concluding his siege comes from an English epic poem dated in the 14th century and it is illustrative that Flavius Josephus, the main source we have for knowing that period, does not mention such a thing .

Now, the most famous case may have been that of Scipio the African with Carthage. After the Second Punic War, the one in which Hannibal Barca was defeated, there was still a third one, half a century later, caused by the non-payment of compensation to Rome and the declaration of war against Numidia, whose king, Masinissa, carried out continuous incursions into Carthaginian territory ruining its economy. The Romans placed deliberately leonine conditions on Carthage so that they would have no choice but to reject them, thus giving them the excuse to totally destroy the city, enslave all of its inhabitants, and declare the site a sacer , that is, cursed or execrable, proceeding to salt it.

In short, the tradition of salting the earth endured because its metaphorical character is undoubtedly strong and, logically, taking into account the link it had with The Bible and the presence in other more or less important historical moments, was collected in the Middle Ages. Especially in the Italian republics:although there is no evidence, it is said that cities such as Padua were salted by Attila (his alleged brutality was compared to that of the Assyrians), Milan by Emperor Frederick Barbarossa in the context of the Guelph-Ghibelline wars , and Semifonte by the Florentines for their support of Siena. Even Pope Boniface VIII ordered Palestrina to be salted in 1299 due to his enmity with the Colonna, evoking what was done with Carthage.

From the Middle Ages it passed into the Modern Age. Since always and throughout the world, the sentences for treason and lese majesty used to be atrocious, with the criminal being dismembered prior to his death and the subsequent distribution of his pieces for display at the gates of the cities; but in Spain and Portugal it was also common to demolish the guilty party's house and throw salt on the lot. There is a fairly famous case, that of José Mascarenhas, Duke of Aveiro, whose participation in the attack against King José I in 1759 led him and his family to the gallows (what is known as the Távora Trial, although he was pardoned Women and children). A stone monument attests to the facts.

Also Portuguese is another famous episode that occurred in colonial Brazil in 1789, when Joaquim José da Silva Xavier, alias Tiradentes (to whom we dedicate an article), led a revolt against the Crown that was relentlessly repressed, culminating in the execution of those involved. He, of low birth, was sentenced to be hanged and dismembered, and his house was "razed and abandoned" according to a paroxysmal sentence signed, literally, with blood.

Now jump ahead to 1986. An Australian historian named Ronald Thomas Ridley publishes in the scientific journal Classical Philology a groundbreaking article in which he refutes the real existence of the custom of salting the earth in ancient times, at least as it was accepted until then. Two years later, three other researchers endorsed his thesis (oddly enough, one of them had been criticized earlier by Ridley for not being analytical enough on the subject) and traced the origin of the myth back to as late as 1905.

In essence, what they were saying is that salting the earth was nothing more than an extension of a symbolic act from Antiquity in which a plow was passed when founding a city or destroying it, something of which there are certain testimonies. Pope Boniface VIII himself, whom we mentioned before, wrote that before ordering salt to be poured on the ruins of Palestrina he subjected it to the plow "following the example of ancient Carthage in Africa" . In other words, it would have been a 13th-century pontiff who created a myth that lasted over time, perhaps by confusing or mixing the Punic capital with Shechem.

However, it was in the mid-nineteenth century when it truly settled and spread, taking as a reference, once again, the aforementioned destruction of Shechem. It was in The New American Cyclopaedia , whose fourth volume, published in 1858, reviewed the conquest of Carthage by Scipio Emiliano saying verbatim:«He took the city by storm and destroyed it, knocking it to the ground, passing the plowshare over the site and sowing salt in the furrows, the emblem of sterility and annihilation."

There has been no shortage of calculations on how much salt would be needed for that. The journalist Cecil Adams raised it in 2007 in his scientific column The Straight Dope , published in The Chicago Reader , and the result was that 31 million tons were needed for each acre to render it infertile; to change, about 7 kilos per square meter. If, according to some estimates, Carthage had a perimeter of 37 kilometers, it turns out that its surface would be 109 square kilometers, which would require 763,210 tons of salt. And since Roman ships of the time were between 70 and 150 tons tonnage, 5,000 to 10,000 ships would have been required for the mission. Obviously, other archaeologists consider these proposed measures for Carthage to be exaggerated, but even so, half the number of boats is still too many.

The most curious thing about Ridley's thesis is that, perhaps, the salt was not intended to have a negative meaning. The image of the Dead Sea, in whose waters there is no life, may have weighed too much. Written sources often speak of sowing it instead of pouring it into a layer, and Boniface VIII's testimony also goes along these lines:«Ac salem in ea etiam fecimus &mandavimus seminari» (And we also put salt in it, and ordered it to be sown.) Why? Because a well-adjusted dose not only does not kill the land but fertilizes it, always depending on the degree of natural salinity of the soil.

It is something that was already known in the classical world, as the Greek philosopher Theophrastus says in several of his works, detailing that some date farmers, for example, added salt to their fields to improve the growth of palm trees; or that the Babylonians used salt instead of manure to fertilize the farms. Pliny the Elder is another who reviews something similar in the Natural history of him , also expanding the taste for salt to domestic animals. And let's not forget the unquestionably beneficial expression the salt of the earth , coined in the Gospel of Saint Matthew.

In short, perhaps salting a devastated space did not so much have the meaning of eliminating all possibility of life in it as, on the contrary, regenerating it duly purified. Another mystery of history that will probably remain in the air. Or on land.