The legal language is harsh and cumbersome for most people, something that law students who have to learn the law would surely subscribe to. Would they have it easier if they were written in verse? This was believed by Carondas, an ancient legislator, who applied it to the corpus normative that he made for the polis Greek from southern Italy.

You have to go back to the 6th century BC, when much of the southern coast of the Italian Peninsula, including Sicily, was dotted with Greek settlements forming what was called Magna Grecia . These were colonies established to extend the commercial networks of the Hellenic metropolises throughout the Mediterranean, in an expansion of a fundamentally economic type that reached the Hispanic Levant. The current cities of Naples, Sybaris, Syracuse, Agrigento, Taranto, Selinunte, Locros, Reggio di Calabria, Crotona, Turios, Elea, Messina, Tauromenio and Hímera were born from those localities, just like the French Marseilles, Antibes and Nice or the Spanish Málaga, Denia and Ampurias, to cite just a few examples.

The first to be founded in Magna Graecia was Cumas, around the year 1050 BC. The others have uncertain dates, although most are around the 8th and 7th centuries BC. In any case, they prospered so much that they soon became polities of proverbial wealth and some joined together to form strategic alliances, often with the aim of fighting others, as happened with the league of Crotona, Sybaris and Metaponto against Siris. But the great moment of Magna Graecia came in the time of Pythagoras, the famous philosopher and mathematician, who was a native of the island of Samos but traveled extensively in the eastern Mediterranean. On one of these journeys he was captured by the Persians and sent to Babylon. When he finally got his freedom, he decided to put land (and sea) in between and settled in the Calabrian city of Crotona.

His arrival and his teachings led to the organization of a mass of adepts characterized by an aspiration to ethical purity, of an ascetic and secret type:the Pythagorean Brotherhood, whose members were popularly known as matematikoi because the doctrine of his teacher gave nature an order based on mathematics. The irruption of that movement altered the existing tranquility, originating blows and counter-blows by the power but one of his disciples tried to bring order by enacting a legislative corpus. It was the aforementioned Carondas, who was a native of Catania.

Catania was part of the Chalcid colonies, those founded by Chalcis, a polis from the Aegean island of Euboea, which was then experiencing a period of splendor, as evidenced by those colonial possessions... which meant its end by awakening the greed of Athens at the beginning of the 6th century BC. But before that end, there was time for Carondas to go down in history with his famous laws. In reality, they were not entirely his own, since they were based on those made by Zaleuco, a legislator of disputed history presumably born in the Calabrian town of Locros Epicefirios (current Locri), a colony in the Greek region of Lócrida, hence that regulation was know it as Locrian Code .

The Locrio it was the first written legal code in the history of Greek civilization and was characterized by its favoritism towards the aristoi (aristocrats) but without marginalizing the rest, in addition to relating the penalties to the cause of the crime and involving the public -through the Council- in any attempt at reform (something that had to be raised with a rope around the neck that would serve to hang the individual if not approved, which guaranteed some legal stability). Of the Zaleuco code only fourteen fragments are preserved, all of them quite curious:gouging out the eyes of adulterers, execution of the patient who drank wine disobeying the doctor, death penalty for thieves, attempting a conciliation between the parties before starting a trial , obligation of women to wear white clothes and walk always accompanied by servants and a slave, etc.

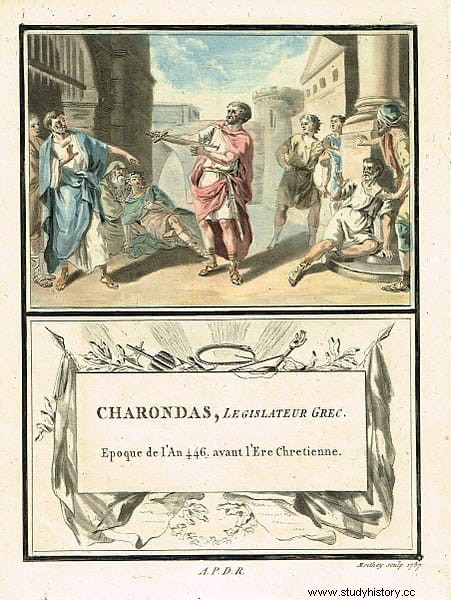

One of the most significant laws for what concerns us was the one that prevented access to the Assembly with weapons. Zaleuco himself was once forced to break that rule by rushing in asking for help to break up a street riot and when he was disfigured he laid down his sword for the sake of social order. We said "for what concerns us" because the anecdote is also usually attributed to Carondas, who apart from being a follower of Pythagoras would also be a continuator of the work of that legislator. And it is that the Code Locrio it was not applied only to Spicephyrian Locris but also to Regio, Sibaris and Crotona, so it must have had an influence on other surrounding colonies.

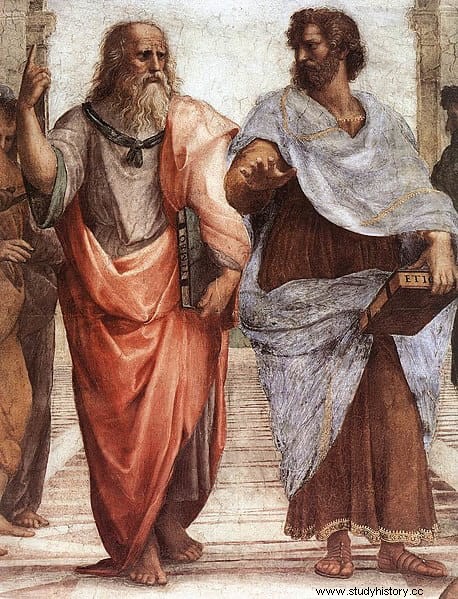

We do not have an original of the laws of Carondas and we know them, among other sources, from the references that appear in the Policy of Aristotle (who praised him for being more specific than Zaleuco) and the Anthology of extracts, sentences and precepts of the doxographer Estobeo, a later millennium. Their character was democratic, understanding as such the concept that was applied in those times when only those who possessed citizenship had the right to vote, from which the majority of the population was excluded:slaves, women, minors and those who had business, that is, not-leisure (those who had to work to live).

That corpus it was intended to favor or, at least, legally equalize the middle class with the nobility, which is interesting since Carondas was situated socioeconomically halfway between the two. However, the reviews of Aristotle and Diodorus Siculus -not always reliable- attribute special attention to what we now call Family Law. He didn't reach the ruthless level of Dracon but still his laws were quite severe, according to the usual parameters at the time. It is believed that the aforementioned episode, in which he entered the Assembly armed and, when the attendees reproached him, committed suicide, is nothing more than a legend disclosed as true by Aristotle and Diodorus Siculus because, as we have seen, the same was also said of Zaleucus and of Diocles of Syracuse. But it serves to exemplify the rectitude of the character.

By the way, Aristotle and Diodorus Siculus, like Stobeus, attribute laws to him that are much later and, therefore, he could never write. That is why there is a shadow of doubt about the veracity -at least the complete veracity- of what they testify to us of his code. Some of those we know about are especially concerned, as we said before, about the family. Thus, the properties of the orphans had to be administered by the relatives of the deceased father while the physical care of the child was the responsibility of the maternal branch; an heiress could demand to marry her closest relative or be compensated by her; the state took care of the education of young people with public funds; and he protected himself from the possible hatred of his stepmothers towards the children of widowers who remarried.

Aside from the family sphere, Carondas also legislated on other issues. For example, that of public life, creating popular courts and punishing both slander and perjury in an unprecedented way:the guilty was paraded before everyone with a vegetable crown on his head. The humiliation extended to the deserters but more seriously, when they were exhibited in the Agora for three days dressed as women. Whoever refused to be part of a jury was fined, a sanction that, with different amounts, also received whoever raped a slave or caused fires. On the other hand, the merchants could only sell their products in the market and the payments had to be in cash, something that two centuries later Plato would pick up in his work The Laws .

Not only the famous Athenian philosopher was inspired by Charondas. The Byzantine Stobeus, whom we cited earlier as a source, also left a series of precepts in the 5th century AD. based on the Greek legislator, according to experts. They were less concrete and closer to moral advice; to roughly :be guided by the gods; secure their favor by avoiding committing evil deeds; avoid despising them, parents and magistrates; seek to have the strength to do what is right; not helping the offender to avoid getting infected and, instead, denouncing him; practice virtue to achieve integrity; honor the dead without exaggerating the pain of their memory; welcome every unjustly oppressed foreigner; set a good example for young people by rewarding the good and punishing the bad; public and state education for the children of citizens; and try to be more prudent than wise.

The most fascinating thing about all this legislative work undertaken by Carondas is that he put it in writing, as we said, but in verse. He believed that this way it could be sung even after banquets and it would be easier for everyone to learn it, remember it and, consequently, respect it. The Athenian playwright Hermipus, a contemporary author of Aristophanes and Plato as well as an enemy of Pericles (he brought a formal accusation against his wife Aspasia for impiety), attested to this in his work On the legislators . All of which strengthens the opinion of historians, who consider Carondas the only reliably historical legislator of Greek Sicily.