Destiny is destiny and no matter how much you try to avoid death, it always arrives faithful to its appointment. There is a famous Persian tale of the man who, to avoid meeting Death, fled from Baghdad to another city and found her there, surprised that she was not in the city from which she came because she had an appointment with him. Something similar happened to Miguel Escoto when, after years of wearing a metal hat, having foreseen that a small stone would hit his head and kill him, one day he took it off when entering a church and, indeed, he died that way.

Of course, it is a legend that circulated in the Late Middle Ages, a century and a half after his death, whose circumstances are unknown and it is only estimated that it occurred around the year 1232. Now, who was that Miguel Escoto so that those and other legendary stories about him arose? Well, he was one of those great multidisciplinary medieval sages, important and famous enough for Dante to include him in his work The Divine Comedy , although not in a place of honor precisely:in the fourth pit of the eighth circle of Hell, where astrologers, sorcerers and false prophets who lied when they claimed they could see the future, suffered:«That other one on the flanks so scarce ,/ Miguel Escoto was, who in truth/ of the magical frauds knew the game» .

The quotation is interesting because it is the only description of Scotus's physical appearance, although it is not known what Dante meant by his reference to the scarcity of flanks. In fact, there are those who believe that it would be something rather metaphorical or even a trait of his character, rather than physical. But the Florentine writer was not the only one who used Scotus as a character. Bocaccio and Pico della Mirarla also criticized his astrological work, while the Frenchman Gabriel Naudé praised him in his Apology . The list is longer and includes Martín Cocayo (Macarrónea ), Walter Scott (The lady of the last minstrel ), John Leyden (Lord Soulis )…

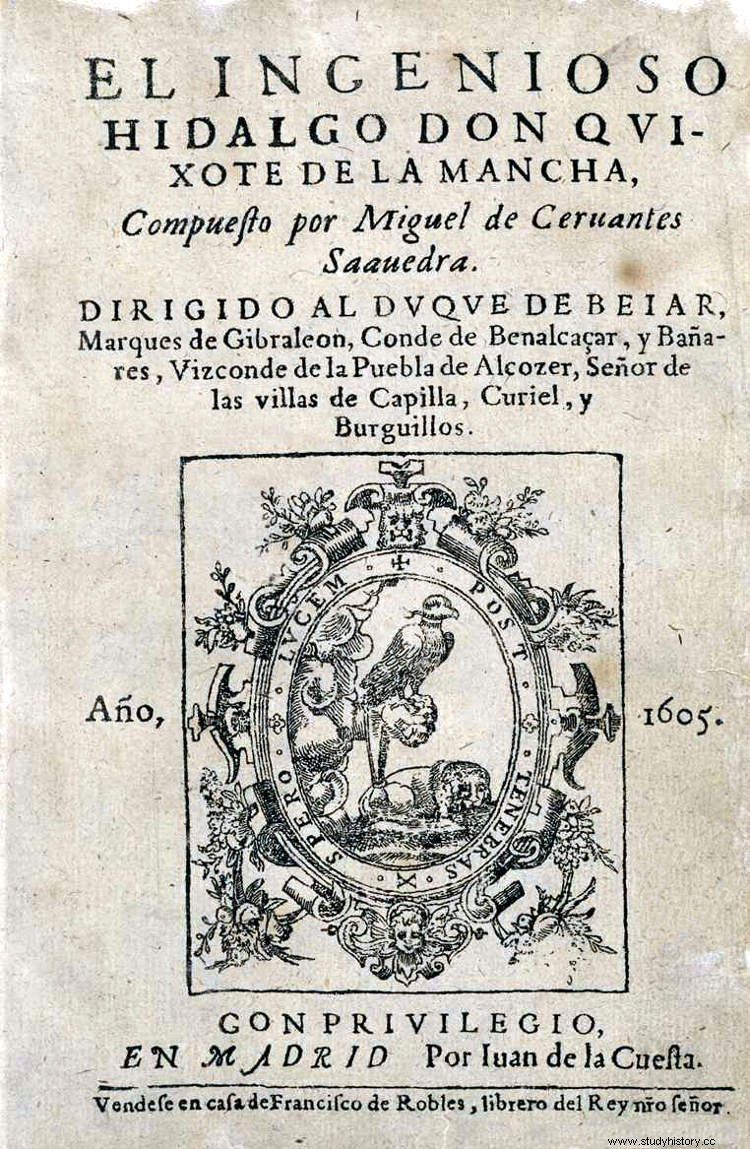

Even authors of the Spanish Golden Age make direct or indirect references, in the case of Luis Vélez de Guevara (the character of Don Juan de Espina, from El diablo cojuelo , is inspired by him), Lope de Vega (canto XIX of La hermosura de Angélica ) or Cervantes, who in chapter LXII of the second part of Don Quixote speaks of a certain Escotillo, a Parmesan astrologer and necromancer who lived in Alejandro Farnesio's Flanders and to whom he attributes things that also characterized Escoto, such as the splendid banquets that both offered with dishes from the French, English and Spanish royal cuisines that, it was said, they brought them spirits summoned ad hoc through black magic.

Miguel Escoto is the Spanishized name that we give him here. The original must have been Michael Scot (or Michael Scotus, Latinized, as was the custom among scholars), since from his surname it seems likely that he was born in Scotland or the north of England, at a time, the Middle Ages, when the borders between both countries changed frequently. Both the exact place and the year are unknown, although it is estimated that it must have been around 1175. It is not recorded anywhere what training he received, although it is clear that it must have been important and surely university, noting that after some beginnings in the Cathedral of Durham (the cathedrals had colleges for teaching), where his uncle would have sent him -with whom he grew up, being an orphan-, he would go on to the universities of Oxford (where he met Roger Bacon) and Paris, since there was no none in Scotland.

In fact, he must have taught at some of them, since he is often listed as magister (teacher). He would have studied philosophy, medicine, alchemy and astrology (a subject that then covered a much broader field than today, including mathematics and astronomy); These last two would be considered a science for a long time and it was rare that the court or noble house did not order the birth chart of the family's newborns or had an alchemist hired to search for the transmutation of metals to obtain gold. And this, despite the fact that, as we saw, there were also critical positions on the matter. In the case of Scotus, this knowledge was expanded with studies in theology and his subsequent ordination as a priest, which put him safe from suspicion.

Moreover, a letter from Pope Honorius III to Stephen Langton, Cardinal and Archbishop of Canterbury, dated January 16, 1223, urges him to grant certain benefits and grant Scotus the Archbishopric of Cashel, Ireland. Escoto, who lived in Paris, rejected the appointment, claiming not to know Gaelic and accepting only the economic part, presumably land in Italy. He knew the Italian peninsula because he had traveled through Bologna and Palermo; From there he took the leap that linked him to the Hispanic world and determined his future. And it is that in 1217 he settled in Toledo, where he learned Arabic well enough to participate in the famous School of Translators.

The Toledo School of Translators was not an academic center but the activity of a group of scholars who, working together or using a common method -there is controversy in this regard-, carried out a vast task of translating into Latin and interpreting classic texts that after the fall of the Roman Empire they had been preserved only in Arabic and Hebrew copies, using the Romance languages as a bridge language, mainly Castilian. This stage began in the year 1085 with the conquest of the city by Alfonso VI and lasted three centuries, with the work of wise Hispanic Christians, Muslims and Jews such as Pedro de Toledo, Domingo Gundisalvo, Juan Hispalense or Marcos de Toledo.

There were also foreigners, in the case of Gerardo de Cremona, Hermann the Dalmatian , Herman the German or several of British origin such as Daniel de Morley, Roberto de Retines, Adelardo de Bath and, of course, Miguel Escoto. The latter, with the new language he had learned, revealed himself to be an accomplished polyglot who mastered Latin, Greek, Hebrew and Arabic, translating the works of illustrious Islamic authors such as Avicenna or Averroes, as well as Alpetragio, an Andalusian cosmologist (in actually called Abū Ishāq Nūr al-Dīn al-Bitrūyī) who wrote Spherae Tractatus , a criticism of the Ptolemaic concepts that would greatly influence Copernicus. The knight and minnesänger Teutonic (troubadour) Wolfram von Eschenbach wrote a poem entitled Parzival in which two of his characters, called Flegetanis and Kyot, represent Alpetragio and Escoto.

But, above all, Scotus was in charge of translating the Muslim versions that had been made of Aristotle:Historia animalium , De partibus animalium and De generatione animalium . This would serve for his fame to spread throughout Europe and thus, after leaving the Iberian Peninsula in 1220 and serving the Holy See (first Honorius III and then his successor, Gregory IX), in 1227, when he was about fifty years old, his presence was claimed by Federico II Hohenstaufen, holder of the Holy Roman Empire, who in his Sicilian court (he was also king of Sicily, where he was born, and of Jerusalem), had assembled a team of wise men and scholars.

Federico was nicknamed Stupor mundi (wonder of the world) for his eccentric personality and his culture, speaking nine languages and being the founder of the Sicilian poetic school and the University of Naples, as well as the author of De arte venandi cum avibu (a treatise on falconry for which he would have had the help of Scotus) and another on philosophy, poems apart. Escoto was commissioned to supervise in collaboration with the aforementioned Hermann el Alemán – A new translation of Aristotle together with the Muslim commentaries that he had attached. But that was only the beginning because then the field of action was expanded with some curious episodes.

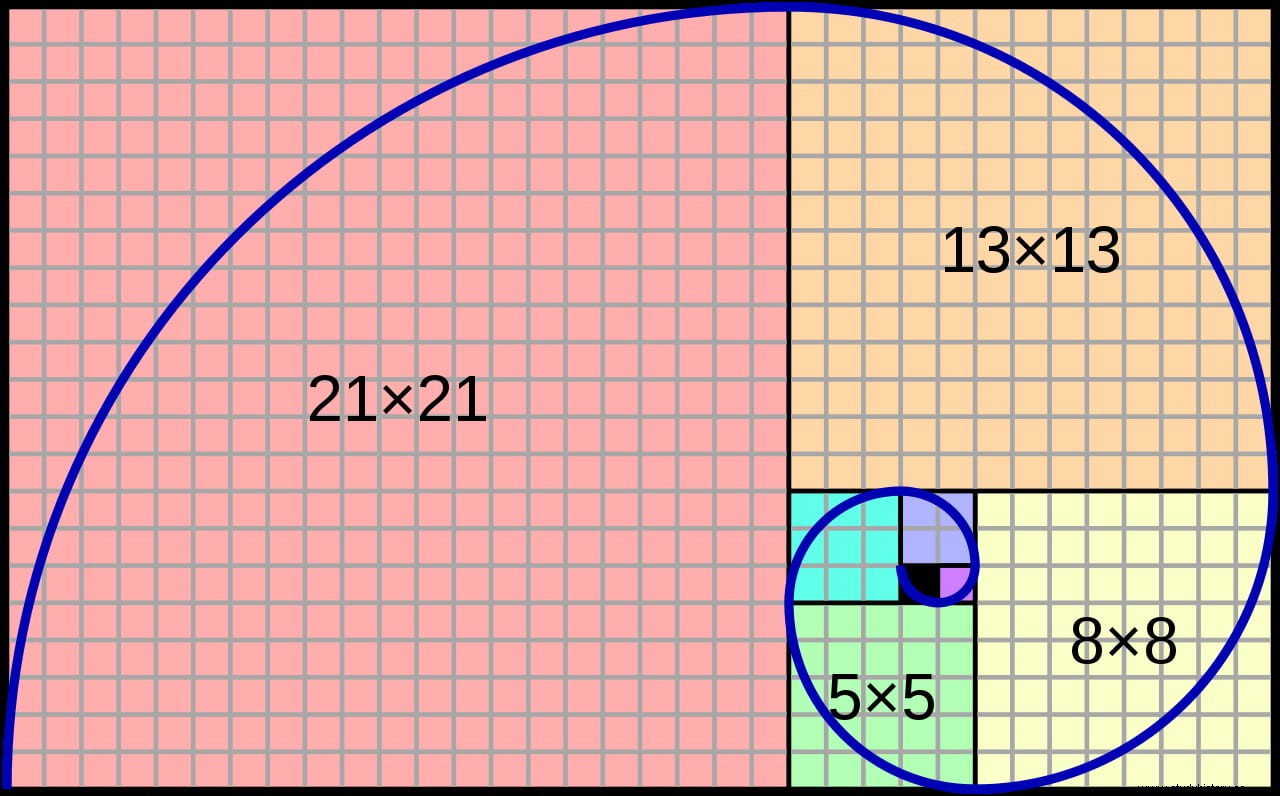

One of them featured Fibonacci, the famous Pisan mathematician, who was the one who spread the use of Arabic numerals in Europe to replace the Roman one. Fibonacci also worked for Frederick II and had just done an extended revision of his Liber abaci (Book of the abacus) that he dedicated precisely to Scotus, according to some scholars for having helped him develop the famous Fibonacci Sequence (an infinite sequence of natural numbers that constitutes the golden spiral, which was believed to be the mathematical basis of nature). Another highlight was Escoto's writing on the multiple rainbow, a phenomenon that could not be physically explained until recently and which has led some researchers to suppose that Escoto may have seen it visiting the Sahara.

All this must often have been accompanied by scientific conversations with the emperor, as seems to be indicated by a letter from 1227 that Federico II sent him asking him about a multitude of geographical, philosophical and metaphysical questions, most of them interrelated:the functioning of volcanoes (he had studied them on-site , in the Lipari Islands); the location of Purgatory, Hell, and Paradise; the characteristics of the soul, etc. Likewise, he commissioned works on specific themes. For example, on the occasion of his wedding with Constance of Aragon, he asked her what would be the Liber physiognomiae , which had a great impact and made its author a pioneer in physiognomy (determining a person's character by facial features), although it deals with more things (the interpretation of dreams, procreation...).

Other Scotus titles were Super auctorem spherae , De sole et luna and De chiromantia , which are quite expressive about their content. But perhaps the most special is the Liber introductorius , a trilogy that includes the aforementioned Liber physiognomiae and which is completed with the Liber quatuor distinguum and the Liber particularis . Completed around 1228, as can be deduced from an allusion to the canonization of Saint Francis of Assisi (which was on July 16 of that year), its underlying theme is the art of divination. After all, Scotus considered that "every astrologer is worthy of praise and honor, since through a doctrine like astrology he probably knows many secrets of God and things that few know" .

The date of Miguel Escoto's death is not known. Some authors, including Walter Scott, tried to identify him with Sir Michael Scot of Balwearie, a diplomatic delegate sent to Norway in 1290, so at least he would have lived until then. However, historians do not believe that he is the same person and, at best, accept that they may have been relatives. So normally the year 1232 is established as the last year of his life, taking into account that there are no news or subsequent publications of his. Could a stone be to blame?