An analysis of ancient genomes suggests that the different branches of the human family tree interbred multiple times, and that some humans carry DNA from an archaic and unknown ancestor.

Melissa Hubisz and Amy Williams of Cornell University and Adam Siepel of the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory report these findings in a study published in PLOS Genetics .

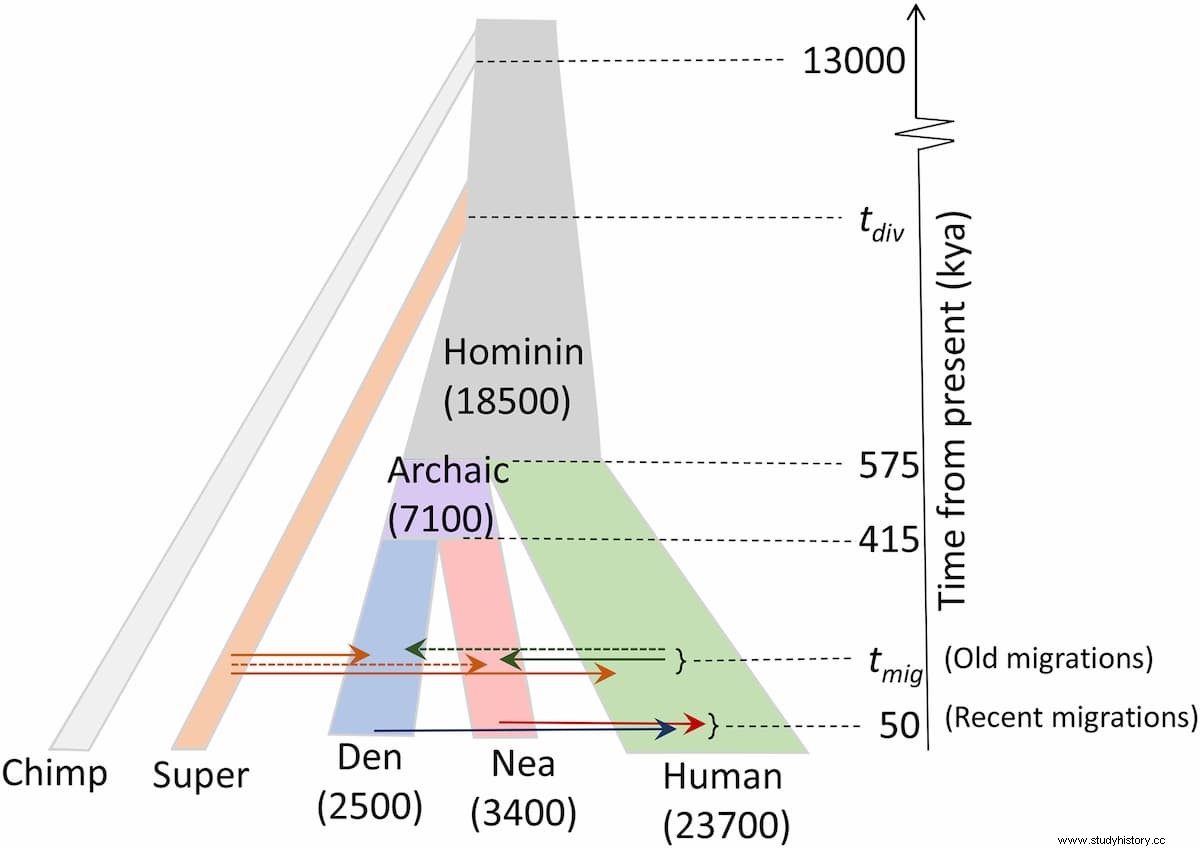

Approximately 50,000 years ago, a group of humans migrated from Africa and interbred with Neanderthals in Eurasia. But it's not the only time our ancient human ancestors and their relatives exchanged DNA. Genome sequencing of Neanderthals and a lesser-known ancient group, the Denisovans, has yielded much new insight into these interbreeding events and the movement of ancient human populations.

In the study, the researchers developed an algorithm for analyzing genomes that can identify segments of DNA that come from other species, even if that gene flow occurred thousands of years ago and came from an unknown source.

They used the algorithm to look at the genomes of two Neanderthals, a Denisovan, and two African humans. The researchers found evidence that 3 percent of the Neanderthal genome came from ancient humans, and they estimate that interbreeding occurred between 200,000 and 300,000 years ago.

Furthermore, it is likely that 1% of the Denisovan genome came from an unknown and more distant relative, possibly Homo erectus , and about 15% of these super-archaic features they may have been passed on to modern humans living today.

The findings confirm previously reported cases of gene flow between ancient humans and their relatives, and also point to new cases of interbreeding.

Given the number of these events, the researchers believe that genetic exchange was likely whenever two groups overlapped in time and space. Their new algorithm solves the difficult problem of identifying small remnants of gene flow that occurred hundreds of thousands of years ago, for which only a handful of ancient genomes are available. This algorithm may also be useful for studying gene flow in other species where interbreeding has occurred, such as wolves and dogs.

What I think is exciting about this work is that it demonstrates what can be learned about deep human history by jointly reconstructing the entire evolutionary history of a collection of both modern human and archaic hominin sequences said author Adam Siepel. This algorithm is able to go further back in time than any other computational method he has seen. It appears to be especially powerful at detecting old introgression.