When Chateaubriand began his journey from Paris to Jerusalem – journey made in , he did not yet glimpse all the difficulties that would accumulate during this trip. The road infrastructures were fragmented or non-existent, the omnipresent danger, but the desire to discover the world was indeed present at the beginning of the 19th century.

I tried the adventure, and it happened to me what happens to anyone who steps on the object of his fear:the ghost vanishes. (Chateaubriand)

At that time, François-René de Chateaubriand had not yet acquired all his letters of nobility, but the reading of the “Voyage du jeune Anacharsis” by Abbé Barthélemy (1716-1795) aroused the interest of all a generation, including his own. Reach Constantinople, which he says is the most beautiful viewpoint in the universe , however, was not reserved for the less fortunate. That said, traveling through the Orient was always possible at a lower cost with the watercolors of Carl Friedrich Heinrich Werner. Imprecise, fantasized and now obsolete, they are not essential for studying the art of this time, but behind the dust the idealization shows us an appetite for discovery. Only, for this very particular century, unattractive to the eye of the convinced modern, has it not given us an even more fertile playground in the image of a thousand years of a so-called obscurantism skilfully maintained ? When we are horrified by a chastity belt, rest assured:it is a myth. And even illustrated in a military engineering book called Belli Fortis (1405), it was only an allegorical and/or satirical representation, well before its popularization in the 19th century.

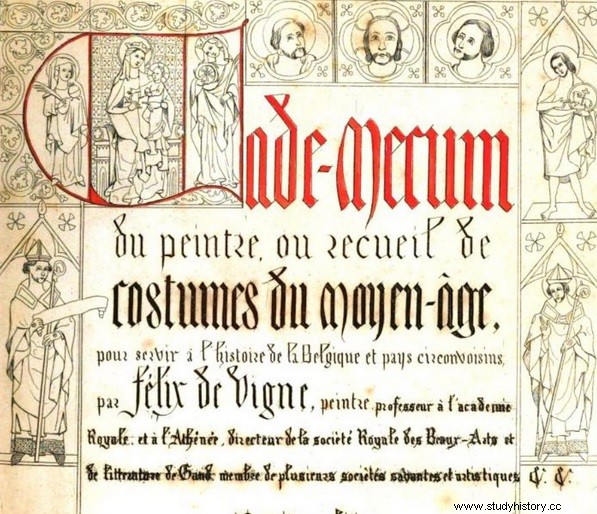

In 1844, the Belgian Félix de Vigne denounces in his work “Vade-Mecum du painter, ou collection de costumes”, the anachronisms in the representation of the Middle Ages and notes that the actors need true and exact costumes. We can legitimately believe that this criticism is still valid today, and yet we are dependent on this 19th century, for better or for worse, which still conceals itself under our interrogations. Did they voluntarily create a fantasy medieval world? When Wagner decides to make his actors wear a helmet with horns during his Der Ring , the trick is played for decades to come:the Vikings will be decked out in this incongruous protection; and many filmmakers, designers and lithographers will perpetuate this myth. Even today, the average person will be able to tell you without batting an eyelid that a Viking must have horns on his head. He is the Barbarian, after all.

We can even record the moment:in 1876, Carl Emil Doepler created horned helmets for the first Bayreuth Festival production of Der Ring of the Nibelungs of Wagner. Paradoxically, the same Richard Wagner will criticize these theatrical costumes for being, he says, far too historical. Of which act.

I cannot conceive that a truly happy man could ever think of art. To truly live is to have fullness. Is art anything other than an admission of our powerlessness? (Richard Wagner)

A Middle Ages with accents of yellowed photo paper in front of a romantic cardboard decor, so this is this golden heritage of the 19th century? Not quite, because above all we owe to this century the extreme liveliness of the European peoples who still considered themselves to play a role in history. It has shaped our perception of past eras, shaken by crises and revolutions which have hardly ceased. A revival full of hope, but also discoveries and energy.

And it took energy to move from the phonograph to the gramophone of Émile Berliner (1851-1929), tyrannical painting that torments the artist like a demanding mistress , as Eugène Delacroix would say, to photography. And from this era of progress that has upset the habits of its contemporaries, it has allowed us to upset our certainties. What Emmanuel Kant will reply that one could not measure the intelligence of an individual to the quantities of uncertainties that he is able to support. Can we today? Our commonplaces for this trompe l'oeil century, however, are constantly being updated.

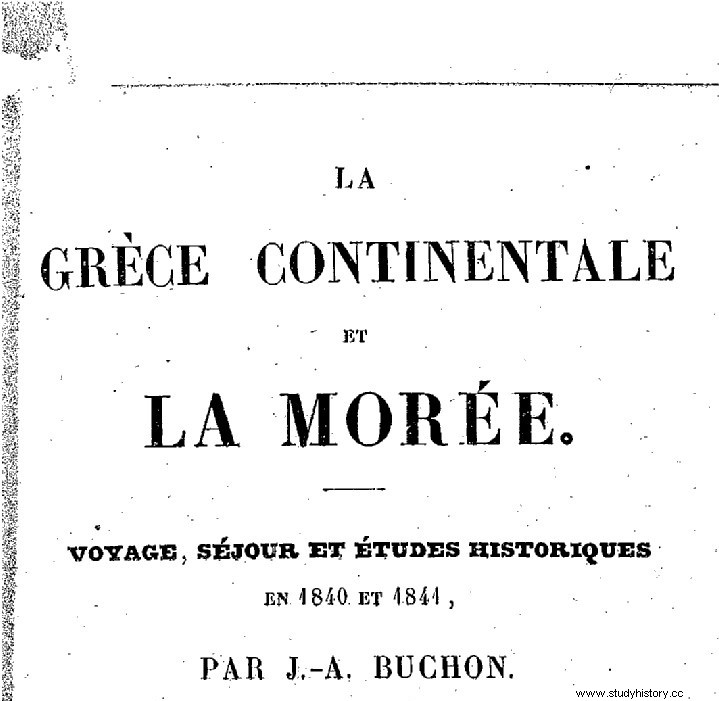

As we now know, this somewhat distorted imagination that has been bequeathed to us has its advantages:it has inflamed people's minds. When the reader read "Continental Greece and the Morea:travel, stay and studies", the work of the French historian J. A. Buchon (1791-1846), he could only embrace his past with the adventures of antiquity, lulled by the taking of Troy (already maintained at length in the 15th century during the mystery shows). The heroes of Greece came to life under immaculate white marble. Admittedly, not all the statues were as we see them today, many of them were sprinkled with pigments – not all of them – but in large quantities. There was not in the minds of our ancestors a quasi eugenic will, as unfortunately we can read in the columns of certain newspapers, but that maintained more the timelessness of an unbreakable antiquity.

If we speak of Greece in glowing terms, its admirable cousin should have our full attention, and, for that, we must then go to Italy, an obligatory stop for architects of this time. The measurements of Leon Battista Alberti (1404-1472) – creator of a new architectural language – will be sobering for centuries to come. As for the wanderings of the French architect Henri Labrouste (1801-1875) – whose work still remains an eminent reference in France and abroad today – they make us dizzy with his 700 preparatory drawings, which the can still be admired thanks to the archives of the digital library of the National Library of France, alias Gallica:http://c.bnf.fr/B1J

Architecture remains a thick file, where sometimes restoration is mixed with reconstruction, but it is also the time for Eugène Viollet-le-Duc (1814-1879) to shine:whether it is the restoration of Notre Dame de Paris and its famous newly erected spire, the Château de Pierrefonds in 1858 (on the recommendations of Prospère Mérimée to Napoleon III), Notre-Dame-de-l'Assomption Cathedral in Clermont in 1866, or even the gigantic works of Carcassonne between 1852-1879 and the Notre-Dame d'Amiens cathedral, the work of which will last 25 years. He will give grain to grind to all his enemies and also inspiration to others, as was probably the case for Louis Cloquet (1849-1920), Belgian architect, author of a veritable little condensed encyclopedia:“Les great cathedrals of the Catholic world” and also author of a “treatise on architecture”.

Their goal is nevertheless clear:to save the heritage in dereliction.

"We have an infinity of old habits that are linked to a civilization... however we have, like the ancients, the faculty of reasoning and a little that of feeling." (The Mérimée and Viollet-le-Duc correspondence).

Moreover, there are centuries which perpetuate societies, make them more significant than others, and we owe it to painters, the romantics in the first place (the worst for this job!), like Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840). Considered the most influential artist of German romantic painting of the 19th century, he firmly refused antique models. The quarrel was always debated:the ancients against the moderns.

Far from the heights of the traveler contemplating a sea of clouds, William Bouguereau, born November 30, 1825, sought to bring art to the middle class with themes of family and pastoral life. We are here far from the conquests and the crash, very present nevertheless in the head of the writers. Charles Martel is a good candidate for this rapprochement, because many works show his popularity; whether in heroic or epic poem in twelve cantos. His presence reminds us that a glorious past of a nation of that time needed to be exalted, vivified and maintained.

“How could the principles die unless the ideas corresponding to them die out? But these ideas, it depends on you to revive them constantly. » The Stoic Thoughts, Marc Aurèle.

From the top of our 21st century, we contemplate with contempt and sometimes disgust the images that systematically send us back to our Great Fear:that of the 1940s and 45s. We couldn't be more wrong with this thought pattern. However, it is this century that begins the so-called modern colonization. No era is crowned with glory, it's no secret.

To radiate without acting, without getting involved in the affairs of the world, is to abdicate, and, in a shorter time than you can believe, it is to descend from the first rank to the third and fourth... Jules Ferry

The ideal is necessarily combined with romanticism:we have seen that their great century will strive to set up padlocked archetypes for a whole generation and the next ones that will follow. Technique calls for technique, and the old will conform to the new And there was an urgent need to save the old:the duty was launched to perpetuate a popular oral language, that of the tales of our childhood.

May it be the one who made the Kalevala (epic composed by Elias Lönnrot based on Finnish mythology) an unforgettable fresco for surveyors of popular tales told in the cottages that we still imagine to be picturesque.

Because in the 19th century, the collection of traditional tales was in full swing in the countryside. Antti Aarne, a Finnish folklorist, embarked on the life-size exercise of classifying and indexing European folk tales. This gave rise to the Aarne-Thompson-Uther Classification by “typical tales”.

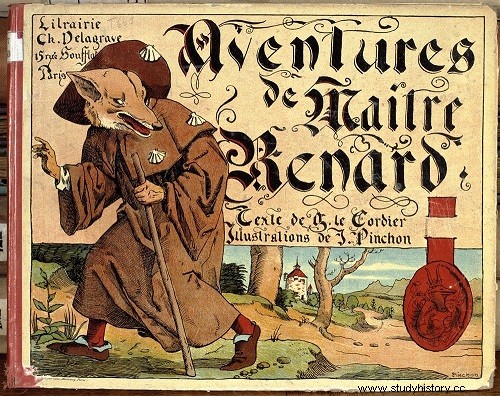

Completed by Stith Thompson (20th century) and Hans-Jörg Uther (2004), a list of 2340 tales are thus listed:Animal tales, ordinary tales (wonderful, religious, etiological), facetious tales or even tales with formulas . Nothing escapes it! Let's not forget Hans Christian Andersen (1805-1875), author of the most famous fairy tales in the world, such as The Little Mermaid, The Ugly Duckling or The Snow Queen. Likewise for the Brothers Grimm – Jacob (1785-1863) and Wilhelm (1786-1859) – , although we will soon come back to these two characters in a future article.

Clearing a whole century is an arduous task, even impossible, and the image of a chipped Epinal that we have does not do justice to the creative effervescence of this century. However, there is an authentic brilliance behind the good formulas of past authors and occasional painters:photochromes. Technical effect very popular at the end of the 19th century, it is not really a photograph, rather a process halfway between photography and painting, created from a negative film then colorized. The Venice of old is dotted with boaters like stilts over a city doomed for the long haul. Let's not hide our pleasure, especially since we can now browse the Library of Congress which includes 6,500 photochromes from the years 1890-1900 presenting cities in Europe, the Middle East, and Canada (see end of article references and sources).

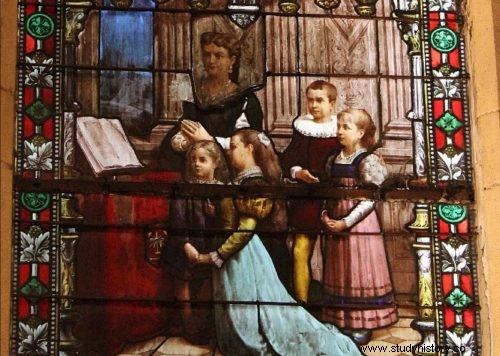

Let's go further in the finds where tradition and modernity rub shoulders:now forgotten, the "photographic stained glass" spread everywhere in France during the 19th century, especially from 1866. This consisted of developing on glass cooks a photograph at more than 600°C to make it unalterable. If believing that reviving this art was easy, think again! the secrets of painting on glass had been lost, at best diluted. Glass painters had become glaziers; chemists, archaeologists and glassmakers were trying to find the right technique for painting on glass. The era in which they lived lent itself well to the revival of the Middle Ages. And if several stained glass windows of this ilk show exaggerated pretensions, they also represented the ideal of hairless (beardless) knights:indeed, they shaved close to the time of the crusades. The beard was then the symbol of the East. Richard the Lionheart, during the Third Crusade, will even go so far as to shave the beards of the Cypriot barons... We never really leave the Middle Ages, it keeps coming back to us like a tintinnabule.

Everything was tried at that time, and this without our perfected instruments, our most accomplished scientific techniques, up to representing protohistory and prehistory:At the end of the 19th century, Maxime Faivre shows us in one of his works what would have could have been France at that time, in his painting “Two mothers” (1888).

In the Japonisme movement at the end of the 19th century, a Japanese word quickly became one of the most beautiful:“Mousmé”. Transcription of the word “musume “, that is to say “young Japanese woman”. Quoted by Proust, immortalized by van Gogh and popularized in Madame Chrysanthème by Pierre Loti. Perfume of exoticism in the middle of the emblematic postcards where the sweet beauty of the women of this time replaced the marble statues. The placid beauty of these women of yesteryear immortalized in these poses are like the caryatids and the Venus de Milo:unforgettable. Because, as historian Michel Pastoureau reminds us, color was vulgar, so black and white was more appropriate.

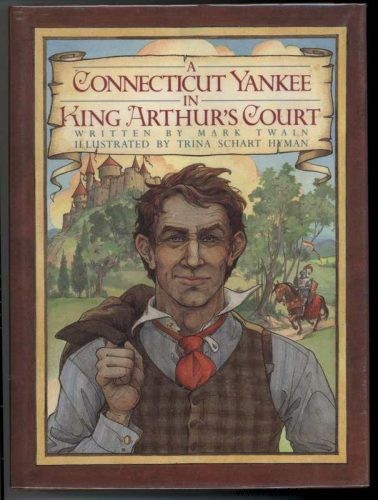

At the beginning of the century, one shuddered to read the “Magus”, a manuscript published in 1801 by the English occultist Francis Barrett, once one of the rarest &sought-after grimoires of its time, Finding information on the secrets of Zoroaster, Hermès or even Roger Bacon are no longer to our liking. At the very end of the 19th century, on the other hand, the mind marveled when the medieval mixed with America at the end of the 19th century, resulting in:“A Yankee at the court of King Arthur”, by the writer Mark Twains. Well after “The Adventures of Tom Sawyer” will spring from his fertile mind, this satire criticizes the medieval romanticism of his time and in particular the novels of Walter Scott.

At the bend of a street, in Drury Lane, in the heart of London, the music of the barrel organ is recorded on punched cardboard. The pressurized air is produced by a pump operated by a crank. In the 19th century, the musical tunes of Verdi, Strauss, Lanner were heard in all the streets thanks to barrel organs.

We end the evening gently with this archive video of 1896:a spontaneous #street dance in Drury Lane, #London.

— History &Odyssey (@HistoryOdyssey) November 16, 2019

You will notice a barrel organ in the background. 1/2 pic.twitter.com/r1rWQzsE98

Period at the height of classicism and at the same time its gravedigger:When we go from David to Vincent, painting will not recover. Marx said that history repeats itself a first time like a tragedy, a second time like a farce. How many centuries can they claim to have triggered so many revolutions at the speed of a locomotive?

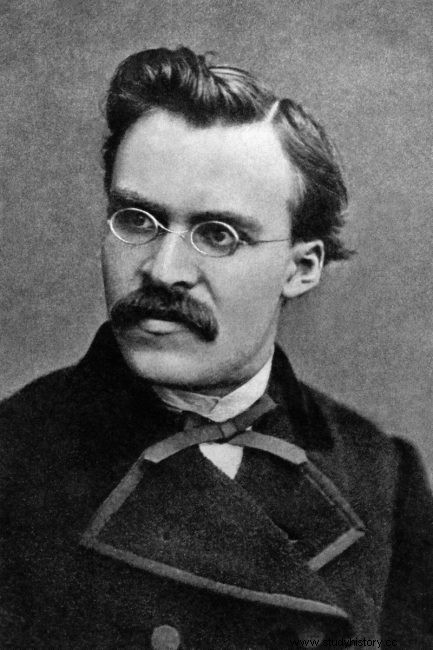

And yet, in all this tumult, the most fertile mind understood nothing of all this. Cursed Schopenhauer, Wagner and his sad music a contrario of a Carmen by Bizet (which he refutes in one of his correspondence, however):Nietzsche. A thinker of his time, he is above all an ancient Greek lost in the 19th century. In “Thus Spake Zarathustra”, a quote will forever be associated with him:“God is dead”.

But he also wonders about the climate, rehabilitates the body (the Great Health) and outlines his “Eternal Return”. The philosopher and philologist gives us “The Birth of Tragedy”, “Le Gai Savoir” or his “Considerations inactuelles”.

All this intellectual progress and this liveliness in the ability to appropriate the story and its components will give Victor Hugo to exclaim:

“The nineteenth century is great, but the twentieth will be happy”.

It is almost impossible to draw a portrait of a time to come, that of a past difficult time. Summing up the 19th century with a date between 1801 and 1900 also involves a risk:nothing really stops at a round number. You will have it, this article is a sketch, fragile, at best a non-exhaustive list which abbreviates and runs to the point. Nevertheless, you will have had the opportunity to discover some flamboyant and more discreet examples of a century filled with a fertile imagination and which still actively works our brains today. Our historical representations are intimately linked to it. The fervor that engendered all this production must not fall into oblivion. Wonder, however, does not make us forget our critical spirit, and this without projecting our modern values from a complicated and cracked era of our ever more lively questions about our gaze on the past. Don't worry, we are not the first to indulge in such a retrospective assessment. George Orwell – the 1984 author – said “Each generation thinks itself smarter than the last and wiser than the next “. And in the effervescence of Art Nouveau that went beyond the digital framework of the 19th century, we could read this in the newspaper La Plume :“The dominant characteristic of a time of transition such as ours is spiritual anguish ” (A. Rette, 1898). He continues:“It is not surprising, because we live in a storm:debris of the past, scraps of the present and seeds of the future” .

Sources and references:

Félix de Vigne's Vade-Mecum

Mainland Greece and the Morea:travel, stay and historical studies in 1840 and 1841

On the Aarne-Thompson classification

Henri Labrouste (Gallica)

The Kalevala:Finnish National Epic (Gallica)

Library of Congress (photochromes)