Born into a family of Spanish descent from Caracas, Bolívar joined the Valles de Aragua White Militia Battalion at a very young age. , where his father exercised his duties as an officer and had a large estate. In 1799, he made a trip to Europe to perfect his military training, although it was then that the independence ideas against the "Mother Country" germinated within him. Already in the rebellion initiated by Francisco de Miranda, in the midst of the Spanish War of Independence, Bolívar gained an important role as the man who convinced the exile in London to return to America.

Portrait of Simón Bolívar, by José Gil de Castro Miranda's prestige having fallen, the Creole ultimately betrayed him in order to get out of this first attempt at independence alive. Bolívar took Miranda prisoner and handed him over to the Spanish Army in exchange for a safe conduct to return to Caracas, although he finally went to Cartagena de Indias with the intention of sparking a new rebellion.

Portrait of Simón Bolívar, by José Gil de Castro Miranda's prestige having fallen, the Creole ultimately betrayed him in order to get out of this first attempt at independence alive. Bolívar took Miranda prisoner and handed him over to the Spanish Army in exchange for a safe conduct to return to Caracas, although he finally went to Cartagena de Indias with the intention of sparking a new rebellion.A civil war between Spanish What came to be called the "Admirable Campaign" gave birth to the Second Republic, a totally personalist regime of the Creole, which moved the war to a new level of violence and social confrontation. Far from the classic account of the struggle of the Americans to achieve their independence from the Spaniards, the successive wars of emancipation that took place in the territories of the Spanish Empire were, in essence, a civil war between Spaniards, that is, Spaniards from America against Spaniards from Europe.

The trials were carried out by Creole owners of large plantations and wealthy intellectuals, who received indirect support from the US and England, beginning with the trade in weapons and warships to the insurgents . Without going any further, the Bolívar family owned extensive cocoa plantations, with encomienda Indians and black slaves. The mestizo and indigenous population fought indifferently on both sides and their situation did not improve, quite the contrary, once the Europeans left.

After successive defeats at the hands of the Spanish Army, the Second Republic of Bolívar fell apart at the same speed it had been created. When Ferdinand VII returned to power in 1814, he was able to organize an expedition of 10,500 soldiers from Spain and reestablish royal power in all the territories. Shortly afterward, Bolívar resigned his command and, in May 1815, went into exile in British-held Jamaica. A period of reflection in which the Spanish Creole abandoned his project of regional independence and subscribed to a continental one. Dressed in democracy at all costs, Bolívar postulated a political system typical of the Latin caudillos, with a president for life and a chamber of hereditary senators made up of the generals of independence...

In 1819, he achieved the independence of New Granada and the birth of Gran Colombia, of which he became a leader. With no time to lose, he promoted a law of expulsion of the Spanish on September 18, 1821 by which all citizens of peninsular origin who did not prove to have been part of the independent movement would be forcibly removed from the country.

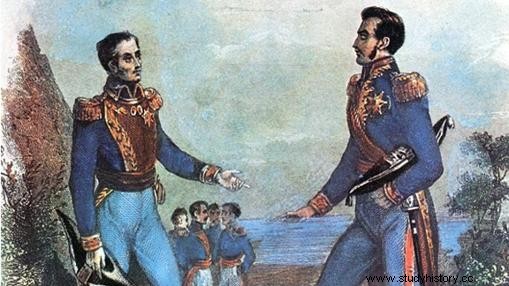

Interview in Guayaquil between Bolívar and San Martín Setting his sights on the south, the almighty Viceroyalty of Peru, he tried to forge an alliance with José de San Martín. During a meeting between the two in Guayaquil, Bolívar disappointedly concluded that the liberator of Peru "did not believe in democracy, being convinced that those countries could only be ruled by vigorous governments that enforced the law, since when men do not obey it voluntarily, there is no choice but force. When San Martín offered him the leadership of the liberating campaign in Peru, Bolívar gave him to understand that he would only accept it if he withdrew from Peru. Either Bolívar or nothing!

Interview in Guayaquil between Bolívar and San Martín Setting his sights on the south, the almighty Viceroyalty of Peru, he tried to forge an alliance with José de San Martín. During a meeting between the two in Guayaquil, Bolívar disappointedly concluded that the liberator of Peru "did not believe in democracy, being convinced that those countries could only be ruled by vigorous governments that enforced the law, since when men do not obey it voluntarily, there is no choice but force. When San Martín offered him the leadership of the liberating campaign in Peru, Bolívar gave him to understand that he would only accept it if he withdrew from Peru. Either Bolívar or nothing!So did San Martín, who headed for Europe, although Bolívar's real problem with Peru was the threat that he posed as a country to his beloved project of Gran Colombia. In the opinion of historian Hugo Pereyra Plasencia, Bolívar came to Peru not so much to give Peruvians their freedom, "but mainly because of the geopolitical interest of rooting out what he considered a threat to Gran Colombia, [...] That is why he creates Bolivia, to cut off the legs of the Peruvian "monster". How little local freedom mattered to him was shown when, in 1825, Bolívar ordered the annulment of the emancipation of the slaves that San Martín had decreed and shortly after he reintroduced the indigenous tribute, which had also been eliminated by San Martín el August 27, 1821.

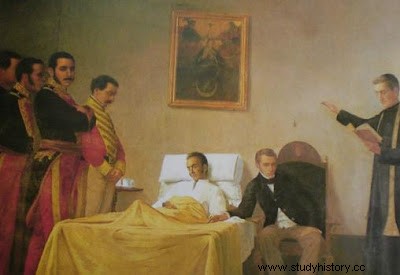

The Death of the Liberator, by Antonio Herrera Toro That same year, the Constituent Congress summoned by him in Peru ordered the erection of an equestrian statue of Bolívar in the Plaza del Congreso, where it is currently, and the payment of a reward of 1,000,000 pesos, an amount that represented, more or less, a third of the annual budget of Peru at the time, as a "small demonstration of recognition" towards his figure.

The Death of the Liberator, by Antonio Herrera Toro That same year, the Constituent Congress summoned by him in Peru ordered the erection of an equestrian statue of Bolívar in the Plaza del Congreso, where it is currently, and the payment of a reward of 1,000,000 pesos, an amount that represented, more or less, a third of the annual budget of Peru at the time, as a "small demonstration of recognition" towards his figure.Bolívar arrived in Peru not both for giving freedom to Peruvians, "but mainly for the geopolitical interest of rooting out what he considered a threat to Gran Colombia"Years of dictatorship Bolívar dreamed of replicating the US in a fragmented, provincial and diverse territory, which in some areas viewed the confederate project with little or no enthusiasm, as in the case of Peru. In the years that followed, the "libertador", who began to monopolize power and act in a despotic manner, failed in his attempt to impose his vision of democracy on the entire continent.

In 1826, the uprising of José Antonio Páez against the order imposed in Venezuela by Bolívar, together with the rejection of the union with Colombia, seriously compromised the Gran Colombia project. Nor did things go as he had foreseen in the Assembly of Panama (1826), where he tried to achieve continental union through a confederation, with participation reduced to Colombia, Mexico, Peru, Chile and the United Provinces of Central America and the commitments just good words.

Furthermore, after the war against the Spanish Empire was over, the Lima aristocracy managed to annul the Bolivarian Constitution that had been imposed on them with Bolívar's argument that, even if the methods to approve it were not legal , was "popular and therefore typical of an eminently democratic republic." Neither then, nor today, Peru keeps good memories of the Liberator.

Simón Bolívar and Francisco de Paula Santander

Simón Bolívar and Francisco de Paula Santanderin the Congress of Cúcuta

Overwhelmed by circumstances, Bolívar assumed full dictatorial powers in a pronouncement in Bogotá in 1828, which led to the Colombian rebellion against his praetorian dictatorship. Among the unpopular measures that he imposed were a series of privileges for the high hierarchy of the Army and the restitution of the alcabala tax, a Spanish tax that had been taken to America after the conquest and about which many Creoles had complained throughout. of the times.

The invasion of the Peruvian army at the La Mar front, the insubordination of his most trusted general, José María Córdoba, and an assassination attempt on September 25, 1828 marked the exit door for him. Bolívar, seriously ill and depressed, presented his resignation in 1830 before the Colombian Congress and lived his last days tortured by the news that arrived of more and more fragmentation of the American republics. He died shortly after in the house of the Spanish hidalgo Joaquín de Mier, in San Pedro Alejandrino.

SOURCE:ABCeshistoria.com