Although at a tactical level the battle of Accio did not have the substance of the great naval battles between the Romans and the Carthaginians in the First Punic War, or those derived from the Sicilian revolt of Sextus Pompey,Accio it marked the end of an era when it came to fighting at sea. With this battle, an era that we now call Hellenistic came to an end, since a new way of fighting, and with a different type of ship, prevailed over the canons in force throughout the ancient Mediterranean until then.

The great oar-ship battles of antiquity are still haunting in our times, and many platitudes about them are simply false. We all come to mind those combats between triremes or quinqueremes with their sails swollen to the wind or moved by the effort of chained galley slaves, evolving against each other, chasing each other, launching incendiary projectiles with their deck artillery and ramming each other at the slightest carelessness until sinking…

How much harm Ben-Hur has done to the Roman navy!

From a fast and light bireme to a gigantic decere , a floating colossus with two masts, two or three artillery towers and ten orders of oars, hence its name, every ship of the navy under normal conditions was manned by free men, soldiers who had the function of rowing, others of navigating and attend to the other matters of the seamanship, others of the artillery and others of fighting on deck. No one was chained in the bilge or to the banks of his oar. This image of a captive galley slave is late medieval or modern, from the times of the Lepanto-type galleys, when the infidels recruited forced oarsmen on the coasts of Christendom. Another great mistake is to think that those ships went out to fight with their rigging set and deployed. The masts and the sails, even the small artemon of the bow foremast, were left ashore on the eve of combat. Nothing was more dangerous than getting entangled with a maneuvering enemy ship or serving as a torch for rival archers... Yes, it is true that the ships rammed each other with their sharp bronze spurs, but the most frequent combat technique was the periplous , hence the word periplo, a kind of permanent turn around the enemy ship in which every possible projectile was unloaded on it until the opportunity arose to board it without facing too many dangers. This is how the Carthaginians had fought at sea, this was how the Cilician pirates had done it and this is how Sextus Pompey had just done it with great success in Sicily until Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa , smarter than hunger, he designed a kind of retractable harpoon that served him to hunt the biremes and triremes as if they were tuna in a trap.

Finally, fire was always the last resort, since it was as dangerous for the one who launched it as for the one who was hit. In Accio the army did use it, but only after Octavio and Agrippa were aware that the squadron of the Queen Cleopatra, and the war treasure that she carried in her cellars, had managed to escape from the siege and it did not matter if they caught the enemy ships intact.

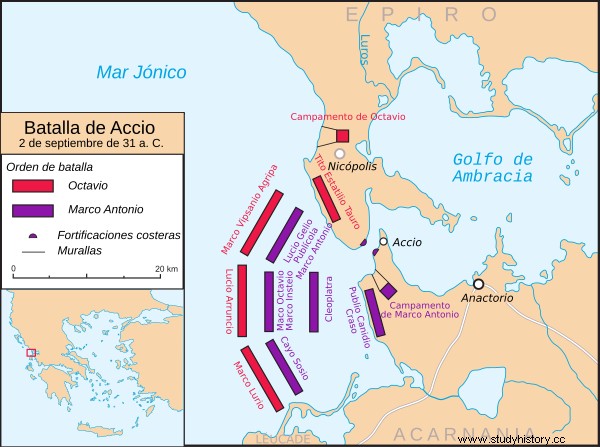

It was the morning of a stormy September 2, 31 B.C. in the narrow mouth of the Gulf of Ambracia, in Greece. That day, Marco Antonio he took out the little more than two hundred ships that he could arm and service and spread them in an arc around the strait, leaving Cleopatra in the rear with the Egyptian squad and the transports and forming three blocks before it, the left flank commanded by Gaius Sosio, the center by Marco Insteyo and the right flank by Gellius Publicola and himself as general supervisor. Opposite Antony's ships was Octavio's fleet. , a little more numerous, but composed almost entirely of biremes and triremes, compared to the heavy quinqueremes, sixes, eights and tens that Antony and Cleopatra had. Marcus Lurio commanded the left flank, Lucius Arruntio the center and Marcus Agrippa , the true military talent at Octavian's service, directing the battle from the right flank, with young Caesar behind him supervising everything.

After hovering for several hours, both fleets waiting, enduring a brief downpour and waiting for orders that did not come, the first movement came from Antony's ranks. His flank and Insteyo's center began to push northwest, trying to stretch and open a gap in Octavian's line. The fighting began on that flank and soon became fiercely engaged. It was already past noon when the natural phenomenon that Antony and Cleopatra were waiting for occurred. The wind shifted to the southeast, thus favoring navigation towards the Peloponnese. According to her established plan, the queen weighed anchor as soon as her navarch alerted her to the change. That was the real battle plan:wait for the favorable wind to release cloth and escape quickly and swiftly from that infected mousetrap that the Gulf of Ambracia had become...

The movement of Antony's right flank caused Octavian's line to break in the center, leaving a gap of almost two miles that Cleopatra quickly took advantage of to get out of there at full speed. While this was happening, Antony was stuck on his flank, where Agrippa's light ships had the upper hand, relentlessly harassing his heavy ships on periplous .Antonio had to change ships and catch up with the queen with a group of lagging ships. Gellius Publicola and Marcus Insteyo remained at the mouth of the Gulf of Ambracia, disguising a full-fledged escape as a battle. Plutarch and Dio Cassius agree in narrating how the fleet of Antony and Cleopatra went out to “combat” with their masts set. As we have seen, no navarch of Antiquity in his right mind would have lined up his ships for battle with masts and sails set. Obviously, that was not his plan, and Octavio knew it thanks to the opportune denunciation of Quintus Delio, one of the legates and closest collaborators of Antony who had changed allegiances shortly before the battle because of his personal grudge against Queen Cleopatra.

The consequences of the Battle of Accio were terrible for the odd couple. Gaius Sosius surrendered his left flank without having fought, a lack of belligerence presumably agreed with Octavio, nothing more was known about Gellius and Insteyo, perhaps they fell covering Antony's escape, and Publius Canidio Crassus, his best trusted man on the mainland, he fled to Egypt with what he was wearing shortly after the battle after his nineteen legions had surrendered to Octavian. Antony and Cleopatra saved the war chest and nearly seventy ships, but were left with no veteran regular troops and no one and nothing to stop Octavian. It was only a matter of time to catch them in Alexandria. The path to the principality had been cleared for Octavio.