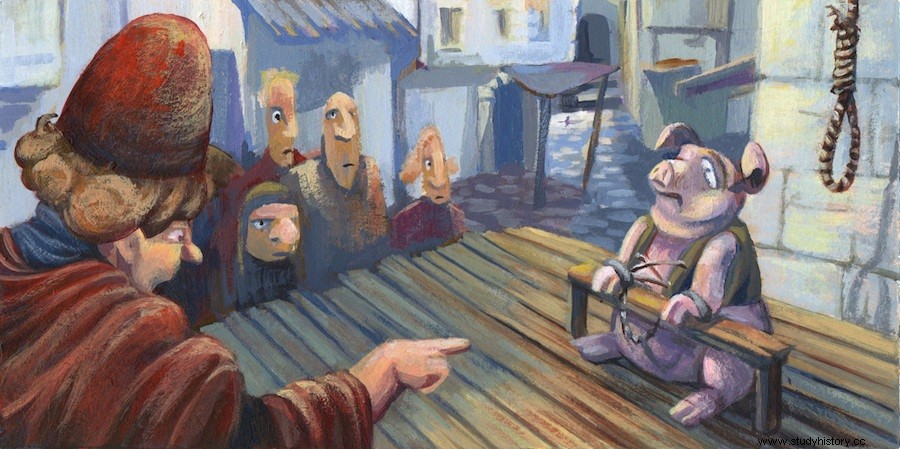

On January 10, 1457, justice was administered in the courts of Savigny according to the following facts:“On the Tuesday before Christmas, recently past, a sow and her six piglets, currently imprisoned, were caught in flagrante delicto of murder and manslaughter in the person of Juan Martín… ”

The judge issued a final sentence in this way:“We say and pronounce that the sow, due to murder and homicide committed by her and perpetrated in the person of Juan Martín, be confiscated to be punished and sentenced to the last torture, and to be hung by the hind legs of a tree……regarding the piglets of said sow, since it is not proven that they ate from said Juan Martín, we are content to return them to their owner, by means of a guarantee to return them if it turns out that they ate from said Juan Martin. ”

The unfortunate sow, led down a road, was immediately executed in compliance with the sentence. We do not know if, as documented in other cases, all the pigs in the village were gathered to witness the execution, as an example of the punishment that would await them for similar acts.

From the Middle Ages until well past the seventeenth century, courts of law were content not only to bring before them two-footed criminals, but also four-legged beasts. The animal perpetrator of the crime, whether it was an ox, donkey, pig or horse, was arrested, imprisoned and tried with all the formalities, and if necessary, was publicly executed as punishment for his misdeeds. They were summoned and brought before the court, they were assigned a defense attorney, logically ex officio, who swore to carry out his functions "with zeal and propriety", all kinds of legal procedures and resources were put into play:dismissals, dilatory exceptions, extensions , vices of nullity... All the tools of the current legality.

A young French lawyer of the fourteenth century, Bartolomeo Chassané, in the account of one of his cases in which he defended a group of mice, recounts how he managed to annul the first session of the trial because “the defendants had not been summoned in time and form ”. The mice were so numerous and lived so dispersed throughout the territory that a single summons nailed to the door of the cathedral was of no use to notify them of the celebration of the hearing. For this reason, the long-suffering priests of the diocese had to go out to the fields again, this time to read the procedural order aloud so that the rodents would be warned.

Another sentence dated 1519 sentenced some country mice, guilty of eating the harvest, to “evict the fields and meadows of the village of Glurns within a non-extendable period of fourteen days, being forbidden to return in perpetuity… ” A plague of mice was destroying the crops of Glurns (today Switzerland) and the peasants no longer knew what to do. Desperate, they decided to resort to justice and denounced the mice. The town judge, fair and consistent where they exist, admitted the complaint for processing, set the day of the trial for October 28 and, in addition, appointed a defense attorney. Logically, the trial was held in the absence of the defendant... They were accused of destroying the plaintiffs' crops, the evidence was provided, the arguments of the prosecution and the defense attorney were heard, and the sentence was read by the judge. However, what is most curious about the sentence is that a certain leniency was shown towards some of these condemned mice, in keeping with the judicial practice of that time, which conferred certain privileges on pregnant women and children. This is how the sentence continues:“…in the event that some females among said animals are pregnant, or are unable to undertake the journey due to their young age, protection will be ensured for said animals for another fourteen days. " They remained? Did they obey the expulsion order? We ignore it.

Mass trials were not uncommon. In the year 1300, in England, an entire flock of ravens was condemned because, in the interrogation, the judges could not distinguish the cries of the guilty “from those who defended their innocence ”, so he condemned the whole group, just in case. In this case, the defendants were present.

A Maine cat was jailed in a cage for a month, for “courting without authorization ” to a cute kitten whose owner was very moralistic.

And a dog was convicted as an accomplice to a robber who had trained him to steal bags and food. The robber lost his right hand as a thief, but the dog received more clemency “ by his good nature "And because it was considered that he only obeyed the orders of his mistress:they let him go with just twenty lashes.

There are hundreds of documented cases of the judicial and formal prosecution of animals, apart from other more well-known ones in which they were accused of witchcraft (especially cats) but, excepting the latter, why were they prosecuted and convicted? Were they held responsible for their actions? It is likely that the feeling that these incredible and naive procedures suggested was the same that demanded that the house of the criminals be razed or burned to erase the scandalous memory that it aroused in everyone.

A case much closer in time, and therefore more stupid, appeared in the June 1948 issue of the London magazine “Lilliput ”, which tells the story of two Irish setter dogs to whom a Los Angeles lawyer bequeathed £1,500 in his will. After three weeks of debate, the judge summoned the lucky dogs, but, because he could not reasonably answer their questions (?), he denied them the inheritance. Or the cases of the elephant Mary, who was hanged, and the elephant Topsy who was electrocuted...

And what to say if we put the Church in the middle... In 1121, while Bernard of Clairvaux was preaching in Foigny (France), the church was invaded by a horde of flies that bothered the parishioners. Faced with that embarrassing situation, the one who would later be canonized as Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, he shouted from the pulpit:

eas excommunico (I excommunicate you)

The next day all the flies appeared dead.

What I don't know is why he didn't excommunicate the wasp that killed Pope Adrian IV. After delivering a harsh sermon against Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa for his claims to the Papal States, Hadrian IV's entourage stopped at Agnani for the Pope to refresh himself. He went to drink water at a fountain, with the bad luck that he swallowed a wasp that caused him to die by suffocation -the sting swelled the area and caused him to suffocate-.

And not only in the animal kingdom have these types of stupid processes occurred, in the fourteenth century an entire forest in Germany was felled and burned by court order, being declared an accomplice to theft. A thief had escaped from the local authorities by running from tree to tree. The forest was accused of witnessing a crime, failing to prevent it, and helping a criminal escape from the law. The court sentenced the offending forest to death.

Source:From the cats of Ancient Egypt to the dogs of 9/11

Illustration Priscilla Tey