To say that there was a Roman emperor named Postumus probably leaves more than one reader puzzled, since that name does not appear in any of the dynasties that ruled Rome:neither the Julio-Claudian, nor the Flavian, nor the Antonine, nor the Severa, neither the Constantinian, nor the Valentinian, nor the Theodosian, had a Postumus, nor was there one among the other accredited emperors. And yet, Postumus proclaimed himself emperor... although not of the Roman Empire but of one of its territories, the Imperium Gallicum (or Galliorum ).

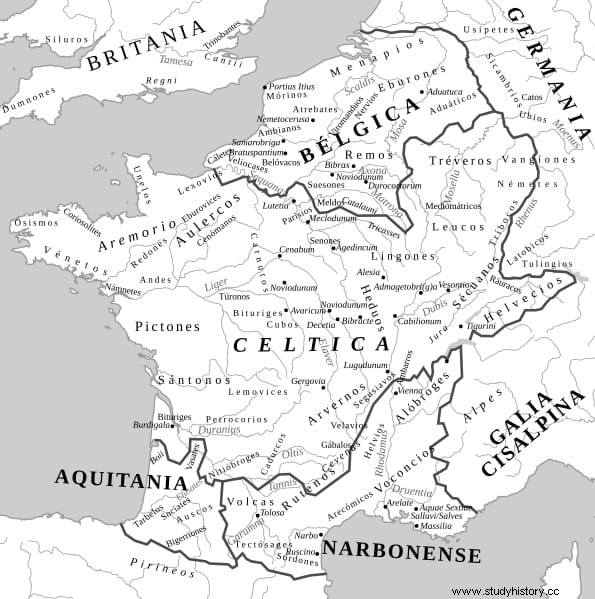

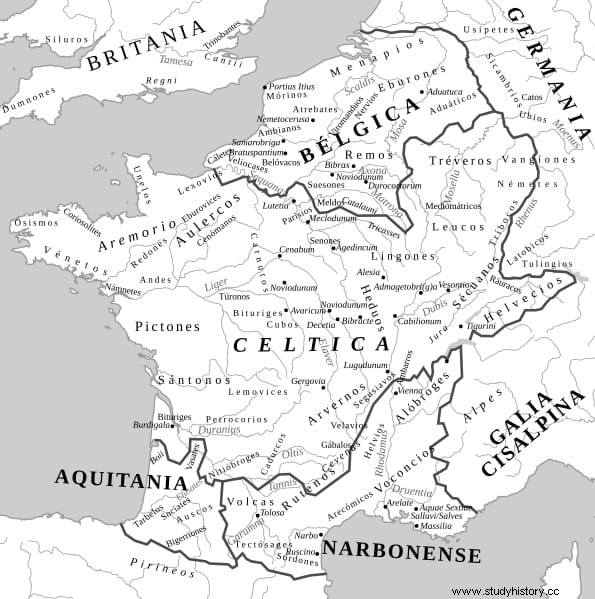

The Romans called Gaul the vast region now occupied by France, Belgium, northern Italy, western Switzerland, and the parts of the Netherlands and Germany west of the Rhine, dividing it into Cisalpina (closest to the Italian peninsula, south of the Alps) and Transalpina (on the other side of that mountain range, also known as Ulterior). The Gauls lived there, a group of diverse peoples, generally grouped under a more or less common culture and with languages from the Celtic trunk.

Julius Caesar conquered them between 58 and 51 BC. Later, Augustus administratively reorganized the territory, creating four divisions:Gallia Aquitania , Gallia Belgica , Gallia Lugdunensis and Gallia Narbonensis . This structure was maintained until the first half of the 3rd century AD, after the death of Alexander Severus and until the arrival of Diocletian, the Roman Empire was shaken by five decades of strong crisis in various fields:political, economic and social. A very appropriate context for personal adventures such as the one undertaken by an obscure character who saw the opportunity to enter History.

His name was Marco Cassiano Latinio Postumus and little is known of his origins. Some suppose him to be a Batavian because he would carry out numerous mintings of coins in honor of divinities that this people used to adore, such as Hercules Magusano or Hercules Dusoniense; others, on the other hand, think that he would be Gallic, given the later behavior of him. In any case, his humble condition not only did not prevent him from ascending in his military career, but he also reached an important position, exactly which one is unknown, although there are those who point to general or even imperial legate (governor) of Germania Inferior .

He must have had good contacts at court or shown great loyalty, as it seems that he could even be granted an honorary consulship. However, the crisis gave him an opportunity that he decided not to miss. In the year 259 AD, the emperor Valerian went to fight the Persians, while his son Gallienus - whom he had associated with the throne - also had to go to guard the borders of eastern Germania, in Pannonia. As hostile movement had been perceived between the Franks and Alemanni, he in turn left to his scion Saloninus the charge of guarding the west.

To help him, he assigned several commands, led by Silvano, his Praetorian prefect, who was also his tutor and had the special mission of advising him and protecting him from the possible ambition of other soldiers. It was prudent, because among them was also Postumus, who after crushing in 260 a.C. an attempted invasion by the Franks, he had become a general as reliable in battle as he was powerful. In the midst of this complex situation, the news arrived that Valeriano had been defeated, imprisoned and had not survived (they forced him to swallow molten gold, it seems).

The commotion was tremendous:it was the first time that an emperor fell prey to the enemy and the empire lost its main pillar, so the bar was opened:up to eighteen generals tried to become emperors. Postumus knew how to fish in a troubled river, taking advantage of a victory he obtained, in the company of Governor Marco Simplicinio Genial, against the Jutungi (an Alemanni tribe):cunningly, he distributed the loot among the troops instead of sending it to Salonino and when he claimed it, he pretended that he was forced to hand it over. As he expected, the legionnaires refused and acclaimed him emperor, defeating and capturing Salonino and his prefect, who did not survive.

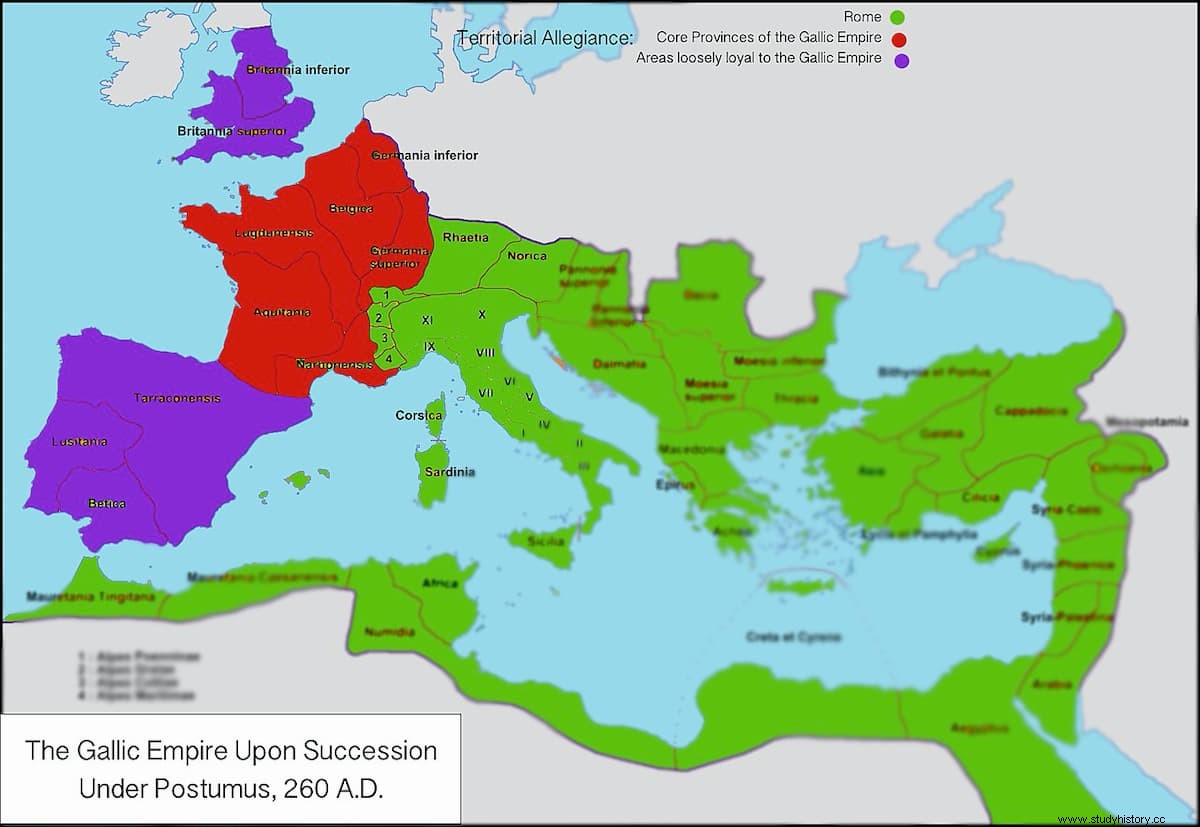

Now, Postumus must have understood that this was an appetizing but dangerous morsel. History showed that the generals who seized power had to face other candidates as ambitious or more than them, often ending up without a throne and without life, so he avoided Rome and was content to be recognized in much of his empire. western:Gaul (except Narbonensis), Raetia, Hispania, Germania and, after a quick incursion between 260 and 261 AD, also Britannia. It is what recent historiography calls the Gallic Empire.

In fact, Postumus minted on his coins the titles of Restitutor Galliarum (restorer of Gaul) and Salus Provinciarum (insurer of the provinces); a year later he added the one for Germanicus maximus , after repulsing the Alemanni. Interestingly, his coins were of higher quality than those of Gallienus and his successors in style and value, indicating that the economy functioned better there than in the rest of the Roman Empire.

And it is that, although it was not an empire itself, since theoretically it recognized the authority of Rome, in practice comparable structures and magistracies were created, in the case of a senate and two consuls elected annually, a pontifex maximus , tribunes, praetorian guard... Many of these positions were accumulated by Postumus himself, obviously, who also established a capital whose exact location is not clear, placing some in Colonia Agripina (current Cologne), others in Augusta Treverorum (Treves) and there are pointing to Lugdunum (Lyon).

The great merit of Postumus was to secure the borders of the new empire. He first managed to abort the two recovery attempts by Gallienus, who is said to have desperately challenged Postumus to a single duel, which the other refused on the grounds that he was not a gladiator and had been chosen by the Gauls themselves. The Roman ended up recognizing him because it was convenient for him to have him as a stopper for the Alemanni campaign towards the Italian peninsula. Then he stopped them and the Franks, which brought a period of tranquility lauded again on the coins with the motto Felicitas Augusti . It lasted five years, from 263 to 268 AD. It had to be a betrayal that put an end to that stage.

Paradoxically, it all started with an opportunity to take over Rome that Postumus let slip in an incomprehensible way:Aureolus, general in command of the city of Mediolanum (Milan) offered to put himself at his service after rebelling against Gallienus. Having such a force and base in Italy would have been a great trump card, but Postumus was uninterested and did not come to Aureolus' aid when Gallienus reacted and besieged Mediolanum. The emperor died during the siege, succeeded by acclamation by General Claudio II Gotico.

Perhaps Postumus had no interest in Rome, as has been said, or perhaps he did not trust his forces, since at that time the Gallic Empire was suffering from a deteriorating economy, perhaps motivated by the interruption of the flow of silver from the Hispanic mines. or because of the problem of continuously maintaining good salaries for the troops to guarantee their adherence. The fact is that in 269 A.D., coinciding with the assumption by Postumus of his fifth consulship, Ulpius Cornelius Lellianus, governor of Germania Inferior, revolted, acclaimed emperor by the Legio XXII Primigenia and the garrison of Mogontiacum (Mainz).

Postumus easily defeated Lelianus taking the city. But when he denied his men permission to plunder it, they turned against him and took him out of the way, appointing in his place a simple officer named Marcus Aurelius Mario. Of course, it did not last long:in two or three months he was also dead and Marcus Piavonius Victorinus, a Gallic nobleman who had been a consular companion of Postumus and now occupied the tribune of the Praetorian Guard, took the reins.

The Imperium Gallicum was thus saved, albeit diminished:Claudius II took advantage of the situation to recover Hispania, Britannia and the parts of Gallia Narbonensis and Aquitaine over which Rome had lost control in the past and which now returned to the fold because the south, after all, After all, it was more Romanized. Victorino tried to recover those territories -except Hispania, where he had not been recognized as emperor-, but unsuccessfully, despite the fact that Rome had several open fronts at that time. He died early in AD 271, at the hands of Attitian, one of his officers, apparently in jealous revenge; the ephemeral emperor would have seduced his wife.

According to some sources, his son and heir, Victorino Junio, would have fallen along with his father, so the widow spent a fortune bribing the army so that they would deify her late husband and name Gaius Pius Esuvius Tetricus as his successor, who had been senator and governor of Gaul Aquitaine. He reigned in association with his son Tetricus II, spending most of his time repelling Germanic invasion attempts. Installed in Trier, they recovered areas of the lost Gallic provinces and suffocated the attempted secession of Gaul Belgium, where Governor Faustino proclaimed himself emperor in parallel, just as Domitian II had done when Victorino died.

But the real danger was once again Rome. In the capital of the empire, Aurelian had neglected the west as he embarked on a campaign against Queen Zenobia of Palmyra, hence the loss of Narbonensis and Aquitaine. But he returned victorious and decided to take them back in early 274 AD, resoundingly defeating Tetricus at Chalons; According to sources, the vanquished did not trust his own troops and agreed on the outcome of the battle beforehand. Perhaps that is why he not only forgave him (and his son) but also appointed him senator and governor in Italy, thanks to which he had a long life and would die of natural causes years later.

It was the end of the Imperium Gallicum , one of the clearest exponents of the crisis of the third century. Twenty years later, the episode was repeated in northern Gaul and Britannia courtesy of Carausius, who we have already discussed here. Some historians interpret these ruptures as the first and incipient outbreaks of the disintegration of central power that will characterize the transition to medieval feudalism, along with military atomization, barbarian invasions, the decline of urban planning due to the fall of trade and a few other factors.