Surely the reader will remember that some time ago we dedicated an article to Robert the Bruce, King of Scotland who was the true Braveheart , despite what the Mel Gibson movie showed. Well, Robert had several brothers and one of them not only helped him get the throne but he also reigned, although he did not do it in his native land but in Ireland, where he had grown up. He was called Edward Bruce (or Edubard a Briuis, in medieval Gaelic) and he was the last Ard Ri or Supreme King of that country.

Edward and Robert's father was Robert the Brus, 6th Lord of Annandale, Earl of Carrick and Lord of Hartness, Writtle and Hatfield Broad Oak; a border nobleman, then, who took part in several contests of the time, such as the Ninth Crusade, the Second Barons' War, the Welsh Wars or the independence of Scotland itself. In 1267 he married, without royal permission, the widowed Countess Marjorie de Carrick, by whom he had five sons and four daughters; one of these, Christina, was the eldest, but the succession corresponded to Robert, the second (whose inheritance was about to be lost because the family had their properties confiscated as a sanction for that unauthorized marriage, although they recovered them by paying a fine). ).

Edward was the fifth to be born, although the exact date is unknown, being calculated around 1280 because in 1307 he already appears in war chronicles commanding a troop. He did not participate in the litigation that Robert had with his mother for the ownership of the inheritance, which supports the theory that as a child he was sent to Ireland to grow up there, following an old Scottish and Irish Gaelic tradition; it is noted that he went to Ulster with the O'Neills or to the Glens of Artrim with the Bissetts.

What he did do was fight alongside Robert in his fight to reach the throne, once Robert successively reneged on his two oaths of fidelity, first with respect to the Scottish king John Balliol (from a branch of the same family that prevailed to the Bruces) and second with respect to the English Edward I, who overthrew the former and definitively took possession of Scotland in 1304, defeating and executing William Wallace. Robert then assumed his candidacy, got rid of his rival John Comyn, and two years later was crowned at Scone (whose famous stone had been taken to London as spoils of war). It was an open challenge to England.

The war had not been easy, alternating victories with defeats (in fact, the Bruce brothers were taken prisoner and the three minors, Niall, Thomas and Alexander, died in captivity). But Eduardo I also died and his successor, Eduardo II, released the others, who took the opportunity to resume the rebellion. Edward Bruce fought brilliantly, taking several castles in the south-west, including Rutherglen in 1313. Even luck was on his side:a dark pact he made with the governor of Stirling Castle, allowing him to ask the monarch for help. English could end in disaster and, on the contrary, led to the Battle of Bannockburn, fought at the foot of the fortress in June 1314.

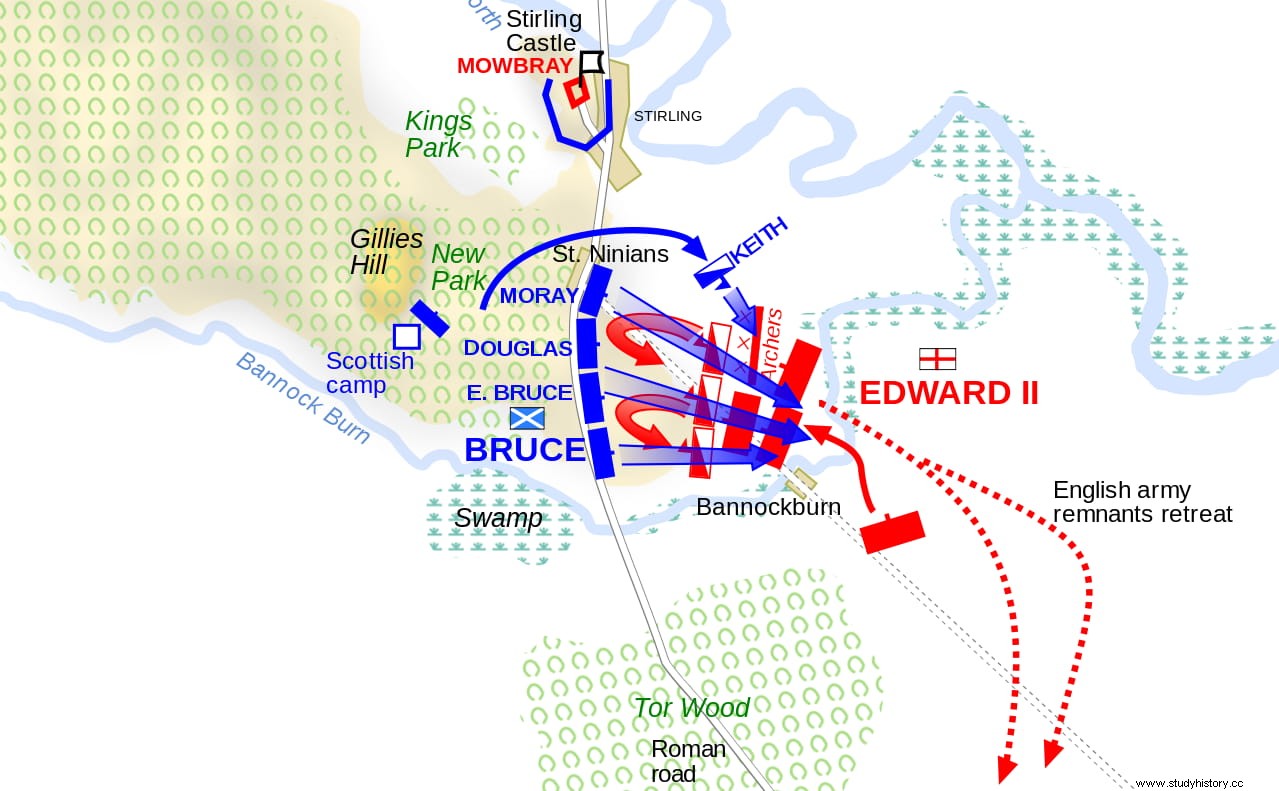

In that clash, Edward led a flank, which he organized as a schiltron , just as Robert and Thomas Randolph did in the rear and vanguard respectively. It was a formation similar to a phalanx, a wall of shields and pikes, either circular (static) or rectangular (movable), which had already been put into practice by William Wallace at the Battle of Falkirk (1297), probably inspired by the ancient pictish war tactic. But if at that one he had failed before the enemy's archers and cavalry, at Bannockburn it was victory and Edward's award of the county of Carrick.

A few months later, at the beginning of 1315, the English began to recover from the heavy blow (nine thousand casualties) and planned a new invasion. Indeed, in January they took possession of the Isle of Man, which constituted a danger for the Scots by opening the possibility of using it as a bridgehead. It was necessary to create a distraction and it occurred to Robert to open a second front in Ireland, because he had the right man for it:his own brother who, let's remember, had grown up there. Edward set off accompanied by Randolph, taking advantage of the fact that Domnhall Mac Brian O'Neill, king of Tyrone, had asked for help when he was attacked by the English settled in Ulster.

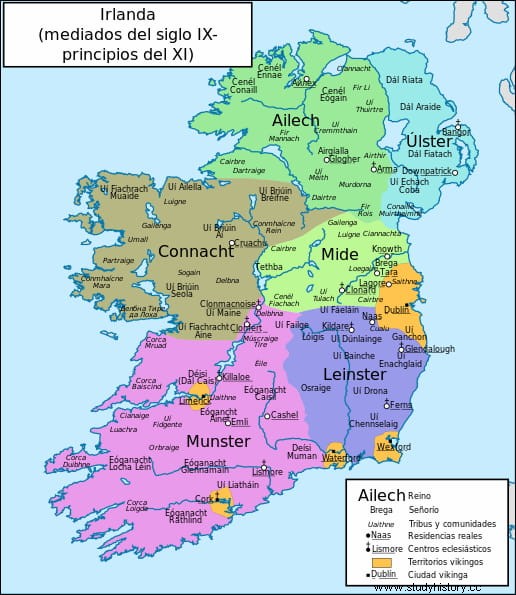

Tyrone was the Anglo-Saxon name of what was called in Gaelic Tír Eóghain (Land of Éogan), a kingdom founded by the homonymous monarch of the Cenél nEógain dynasty, of the Uí Néill clan, and brother of Niall Noígíallach , one of the High Kings of Ireland. The island was then divided into five small kingdoms whose superior authority was the Ard Rí na hÉireann (Supreme King or Great King), a title with half-historical and half-mythical roots that was initially more honorific than practical, a primus inter pares without real power, although later it became a position coveted by all.

The last Ard Rí na hÉireann , before the Norman invasion ended that office, he had been Ruaidrí Ua Conchobair (Rory O'Connor), King of Connacht, who was on the high throne between 1166 and 1198, except for Brian Ua Néill's attempted revival (Brian O'Neill) from 1258 to 1260, failed to die at the Battle of Downpatrick against the Normans, failing to obtain unanimous support. When Robert agreed to come to Tyrone's aid, he did so demanding in return support for his brother Edward to be crowned High King. The plan was that the former would recapture Man and the latter would attack Wales, so that between the two of them they would form a grand Gaelic alliance against England.

Domnhall Mac Brian O'Neill agreed, since, after all, the Bruces were descendants of Princess Aoife MacMurrough (Eve of Leinster), High King Brian Boru (who probably ended Viking rule in Ireland), and the Viking sovereign Olaf Cuaran, among other complex ancestral dynastic ramifications. Before leaving, Edward was appointed legal successor to his brother, since he had no legitimate children; he was at Ayr, in April 1315, where the fleet was also mustered which was to transport the army from Scotland to the intended point of landing, between Larne and Glendrum.

By this time the news of that operation had already reached England, which he sent to the Earl of March, Roger Mortimer, with the position of High Justice and Lieutenant of Ireland, organizing a defense. Curiously, Mortimer had been imprisoned by the Scots at Bannockburn, although they freed him in an exchange for the royal seal retained by Edward II... whose wife, Elizabeth of France, he would later become a lover of. Edward and Randolph, in fact, landed at the head of six thousand men and soon faced Richard Og de Burgh, Earl of Ulster, whom they defeated at the Battle of Connor, beginning that summer a triumphal march that was pushing the enemy towards the south.

The best moment came with the conquest of the city of Carrickfergus, where they met with a dozen Irish kings for Edward's coronation as Ard Rí na hÉireann and the corresponding vassalage oath. No one expressed opposition, but neither did he obtain the expected absolute support, so he did not achieve the power he expected. To solve it, he made a strategic mistake:trying to subdue the ambiguous by force. This led to attacks on the city of Dundalk and Castle Roche to isolate Ulster, at the cost of alienating him further. However, he was also unable to deal a decisive blow to the English, defeated in all the clashes (Connacht, Louth, Coleraine), but still operative, with Carrickfergus Castle - which he had resisted - as a refuge.

Little by little, Edward began to suffer the abandonment of some allies, but in November he still obtained a new success against Mortimer at Kells, thanks to the fact that Randolph, who had traveled to Scotland in search of reinforcements, returned with half a thousand soldiers and provisions. . Mortimer had to flee to Dublin and there, faced with the imminent assault of his adversary, he sailed for England to, in turn, ask for more troops. Edward took and burned the city, repeating below with Granard and Angaile. As winter was upon him, he settled at Loughsewdy (Ballymore), which he too would demolish before leaving. Much of Ireland was under his control, but hard times were ahead.

And it is that the military destruction of the island plus adverse weather, identified with the beginning of the so-called Little Ice Age (which, with ups and downs, would last until the mid-19th century, although exclusively affecting the North Atlantic), ended with the harvests and they left both sides without food, causing a famine that fell on everyone, aggravated by the consequent epidemics. The period 1315-1317 was terrible in that sense, but the last year with special virulence because the cold killed most of the livestock and would be finished off by rinderpest that began the following year and lasted until 1320. The extremely high mortality caused a collapse demographic. 1319 would give a break, but short-lived; as compensation, throughout the decade there would be a significant improvement.

It was necessary to survive as it was and, to retain his men, Edward had to resort to looting, turning against a large part of the population. That is why he and his allies deemed it convenient to underline the legitimacy of his reign over Ireland by asking Pope John XXII to revoke the bull Laudabiliter ; that document (of which only references are preserved, which has led to questioning its real existence or, at least, the accuracy of its content), promulgated by Hadrian IV in 1155, recognized the Englishman Henry II as king of the island, which served as a justification for him to invade it in exchange for making the Gregorian reform effective in the semi-autonomous Irish Christian Church. However, the pontiff did not want to approve Edward's claim -even he excommunicated the clerics who supported him-, who thus continued to reign only in northern areas.

Meanwhile, the English reorganized themselves and by the end of the summer of 1318 they had gathered some twenty thousand men who, under the command of Sir John of Bermingham, Irish nobleman son-in-law of the Earl of Ulster, marched to meet the enemy army in search of a decisive battle. The clash occurred on October 14 in Faughart, a town near Dundalk (which is why it sometimes also appears by that name in historiography) and the imbalance of forces was effectively decisive. There is not much information about the battle, except that the Scottish monarch was partly to blame for accepting the challenge instead of waiting for reinforcements from his brother, says the Annals of Clonmacnoise (an Irish chronicle, now lost, whose name alludes to the monastery where he was found).

Edward took a high position and placed his Irish allies in the rear, as punishment for being in favor of a prudent withdrawal. In this way, the vanguard was reduced to two thousand Scots, whom, according to the Lanerscot Chronicle (a history of England centered on the period 1201-1346 and presumably made by English Franciscan friars), the king ordered in three lines but too far apart from each other, so that the adversary could pass them successively without being able to help each other.

Although there are no casualty figures, Edward's defeat was catastrophic and cost him his life, his body being butchered and scattered across Ireland as an example, while his head was given to Edward II. The cause died with him, since other commanders also fell, such as Alexander MacDonald, King of Argyll, and Alexander MacRuari, King "of the Isles" (possibly the Hebrides); furthermore, John of Bermingham conquered Carrickfergus Castle on 2 December, for which he was rewarded with the appointment of Earl of Louth.

Very few regretted the end of that adventure; such was the hostility that the looting had aroused. However, it can be considered that it fulfilled the original objective of distracting the English from an invasion of Scotland from the west, since in the following campaign, which lasted from 1318 to 1319, Robert the Bruce managed to break the siege of Berwic, last English stronghold in Scotland, and in 1320 he managed to get the Pope to suspend his excommunication and recognize his authority in the country, to the detriment of English claims. In practice, it was a legitimation of Scottish independence, although in 1322 Edward II would still attempt another invasion that crashed at the Battle of Old Byland and his successor, Edward III, would also suffer a setback in 1327.

The Treaty of Northampton endorsed this independence and recognized the royalty of Robert, who died of leprosy two years later; being his eldest still his junior, Thomas Randolph took charge of the regency. As for Edward's son, Alexander the Brus (whom he had by his late wife, Elizabeth of Strathbogie, daughter of the Earl of Atholl), he inherited his titles save for Ard Rí na hÉireann . In fact, there was no longer any High King of Ireland.