It remains shocking that from the people who invented the alphabet and by extension taught half the world to write, the Phoenicians, nothing of their literature has come down to us except for three fragments of papyrus.

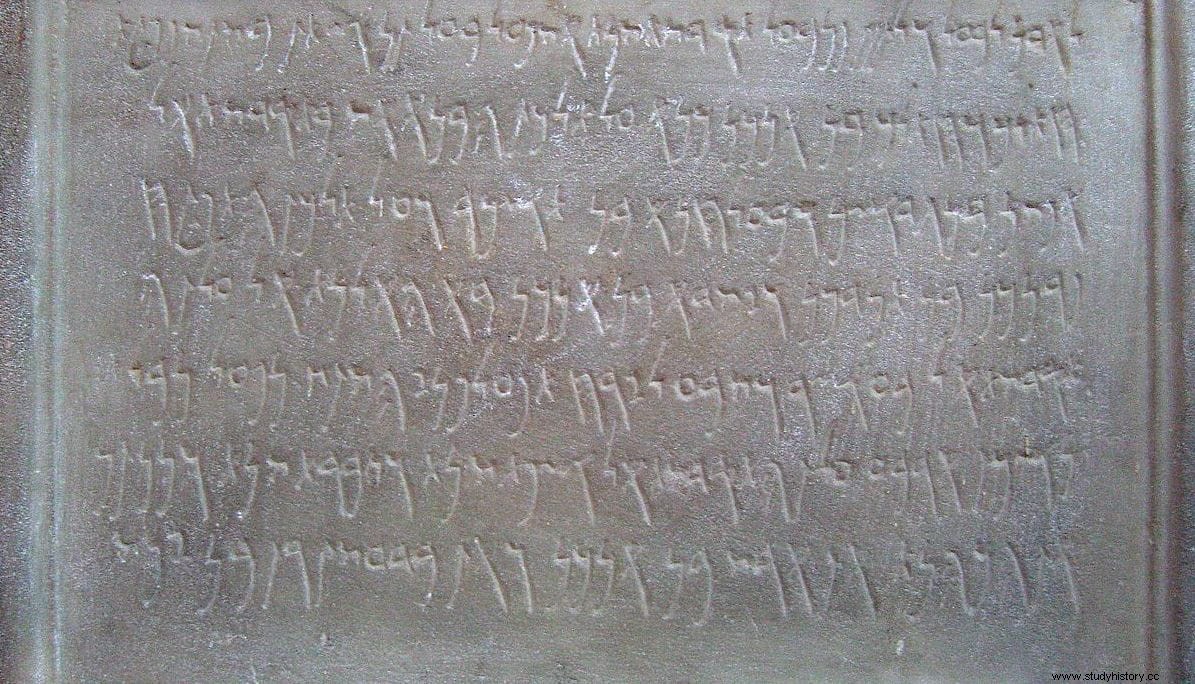

It is true that some 10,000 stone inscriptions and pottery fragments are preserved, but no literary, historical or other works in the Phoenician language survive. One of the possible reasons for this is that the Phoenicians wrote on papyrus or parchment, both perishable media, and for some reason they were not preserved as well as those of other peoples such as the Egyptians.

Phoenician writers and works are known from citations and mentions made by later Greco-Roman authors. Perhaps the most outstanding case is that of Sanjuniatón (in Phoenician 𐤎𐤊𐤍𐤉𐤕𐤍, SKNYTN , pronounced Sakun-yaton ), author of three historical-mythological works that were translated into Greek and published by Philo of Byblos in the 1st century AD.

Philo's translations did not survive either, but they are widely cited by an unlikely fourth-century author:Eusebius of Caesarea, bishop and father of Christian history . He does it in his Praeparatio Evangelica with the aim of discrediting the Phoenician religion, but since there is no harm that comes for good, the quotes are so extensive that by assembling the fragments it has been possible to reconstruct part of the original work of Sanjuniatón. In such a way that they make up the most extensive text we have on Phoenician mythology and religion.

As can be seen, Eusebius did not doubt the historical quality of the text of Sanjuniatón, but he uses it to highlight Phoenician beliefs. In fact his Praeparatio Evangelica , which is made up of 15 books, is made up of 71 percent of quotes from other authors that serve the bishop to document his argument. According to Ignasi Vidiella, in his March 2016 conference at the IV Ganymede Congress of the University of Valencia, the criteria followed by Eusebio to cite the authors is the consideration they deserve . Thus, he cites Diodorus of Sicily, Dionysus of Halicarnassus, Plato, and many others.

De Sanjuniatón points out, quoting Porfirio:

That Sanjuniatón had lived in the pre-Homeric era before the Trojan War seems unlikely, especially when he once quoted Hesiod, who lived around 700 BC. In fact, many modern experts thought that he could never have existed other than as a mythological-legendary character, and it was even suggested that Philo of Byblos himself would have been the true author of the work, attributing it to an ancient writer to make it more believable.

Eusebius also cites Philo himself:

But in 1952 the German theologian Otto Eissfeldt, a specialist in comparative religious history of the Near East, showed that the text incorporates Semitic elements supported by the Ugaritic mythological texts excavated in Ras Shamra, Syria, since 1929. The current consensus is that Sanjuniaten really existed and he wrote his work between the time of Alexander the Great and the 1st century BC

There are several editions that compile the fragments of the work of Sanjuniatón extracted from Eusebio, although we have not been able to find a translation into Spanish. We were also unable to find an available translation of the Praeparatio Evangelica , and we use E.H.Gifford's English, which is in the public domain (see link in sources). The Sanjuniaton fragments are found primarily in Book X.