When Christopher Columbus crossed the Atlantic in 1492, he changed the world forever. And thoroughly! This so-called “discovery” of America by Columbus is viewed as one of the possible endpoints of the Middle Ages, with good reason. What is much less clear is how his rides should be evaluated in the context of time. Was Columbus a daredevil visionary or was he just coincidentally the first to pursue an actually obvious plan? In order to get closer to an answer to this question, I would like to summarize in this article what people in the Middle Ages actually knew about the globe, what opinions were floating around about the size and appearance of the earth and what Christopher Columbus himself could refer to.

This is what the world looked like to the ancient Greeks

As is often the case with such questions, one has to go back to ancient Greece in search of an answer. In ancient times, knowledge of the world was still somewhat limited. However, by looking at the writings of various Greek scholars, one can get a good sense of how the people of that time saw their world. Of course, the fact that we limit ourselves to Greek scholars does not mean that other cultures could not have possessed similar knowledge. The only thing we don't know about them is that for centuries afterwards it was customary to copy Greek sources, not others. As always, we can probably blame the Romans here.

Anyway. What was already known to some extent in antiquity was the shape and nature of the Mediterranean Sea. Most of the old high cultures finally settled along this sea, so it is no wonder that knowledge about it was reasonably well developed. The Phoenicians probably traveled to the end of the Mediterranean Sea (as seen from their side) around 900 BC, the Strait of Gibraltar. Just like I said. Well, no one wrote that down. The same strait was later considered by the Greeks to be the end of the world. The Greeks called the Pillars of Heracles the two mountains that guard the waterway to the left and right - the Rock of Gibraltar on the European side, the Jebel Musa on the African side. After that there was nothing more for her, it didn't go any further behind it. "Non Plus Ultra", one would later say in Latin, which eventually even became Spain's state motto. At least until you discovered America. Since then, the Spanish motto has only been "Plus Ultra". Why not.

The Atlantic behind the Pillars of Heracles was thus unknown for a long time. But he wasn't really important for the Greek world either. All cultures worth mentioning and all treasures were either in the Mediterranean or in Asia, so why should you look west? The fact that an Alexander the Great went east to expand his empire tells us where the priorities of the time lay. But hey! The ancient Greeks wouldn't be the ancient Greeks if one hadn't found one and even during Alexander's lifetime the first Greeks tried their luck on the other side of Gibraltar. A certain Pytheas is said to have traveled throughout Britain, parts of Scandinavia and the mythical island of Thule, which no one knows where it is supposed to be but which was marked on almost every map for centuries to come. The image of the ancient Greeks about the nature of their globe and the placement of the countries on it became better and better. And then there's the fact that they even knew about the globe and that the earth isn't flat...

The ancient knowledge of the globe

The good Christopher Columbus is still sometimes accused of being a visionary in the 15th century because he was one of the few who believed in the spherical shape of the earth. However, this is absolute nonsense. By the time of Columbus, it was well known to almost everyone in Europe (and elsewhere) that the earth was spherical, not flat. It would be a few more centuries before die-hard followers of the "Flat Earth Theory" would question this again and flatten the earth again... This makes the Flat Earthers more ignorant than the ancient Greeks!

It was probably Pythagoras who, in the 6th century BC, was the first influential thinker to speak of our planet as a globe. In any case, the great star of Greek philosophy, Aristotle, was already more than aware of this two hundred years later. In fact, it may have been common knowledge at the time. The exact size of the globe was also an issue for the ancient Greek scientists and was calculated again and again. For example, in the 3rd century BC, Eratosthenes calculated the circumference of the earth to be approximately 41,750 kilometers, which was impressively close to the actual 40,075 kilometers.

The problem:This calculation was probably no longer known at the time of Christopher Columbus. There it was again, the old problem of ancient science. If enough people didn't always find an idea important enough to write it off, it would eventually get lost. This was the case with Eratosthenes' calculation of the earth. As a result, in the 1st century BC, a certain Poseidonios recalculated the circumference of the earth and suddenly came up with just under 35,000 kilometers. A Ptolemy took over this method of calculation again two hundred years later, which was then received again and again up to the Middle Ages. In fact, it's possible that Christopher Columbus thought the voyage from Spain to Asia couldn't take too long because of this miscalculation.

The maps of medieval Europe

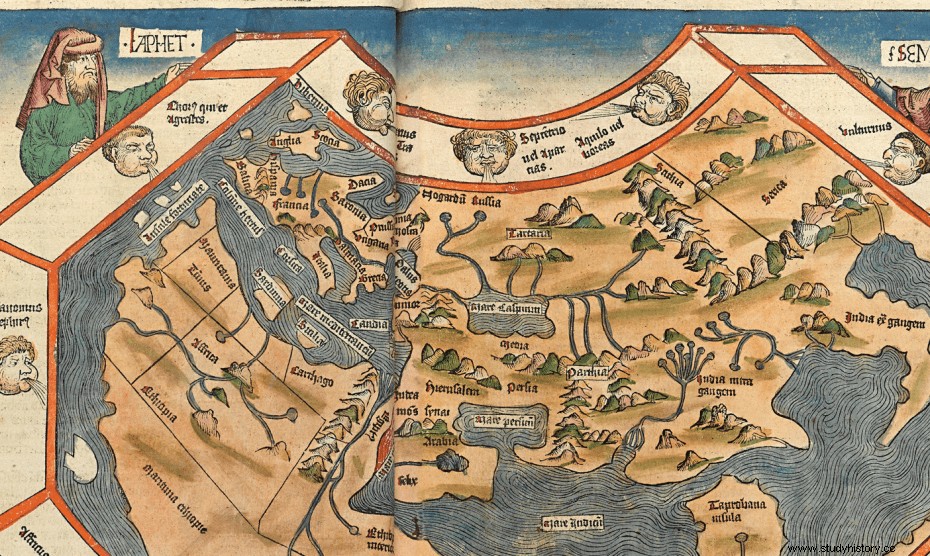

So we can summarize:The idea of the globe, from the nature of the continents to their circumference, was intensively examined by Greek scholars in ancient times with sometimes incredibly exact results (even if the wrong results were sometimes passed on over the centuries became). And even in the European Middle Ages, people still referred to precisely those calculations and considerations. Ptolemy in particular had a great influence here for a long time. They were probably just too lazy to make new calculations. You already knew him.

What is true of the great ideas about the globe is also true of the maps that were available to potential explorers. Almost all of the Greek thinkers mentioned so far also made land and sea charts, some of which came pretty close to reality. Here you can look at the map of Eratosthenes, here that of Ptolemy. And what can one say:These maps have not changed fundamentally over the centuries since. The shape of Britain, the exact location of Scandinavia and other details were gradually adjusted as these areas became more important within Europe. On the whole, however, up to modern times the world maps were strikingly similar to those of Ptolemy.

Christopher Columbus must have used exactly such a map when he tried to get to “India” via the west. Incidentally, India is to be seen as an umbrella term in this context. When Columbus landed in the Caribbean, he didn't think he was in India. Far too much was known about the world in the Far East for that. Rather, he thought he had landed somewhere near Japan. A prime candidate for the actual map Columbus used is that of Henricus Martellus Germanus in 1490, just two years before Columbus left. So this map, and maps of the time in general, may not have been all that accurate. But in the 15th century everyone knew that the earth was spherical. And the good Columbus couldn't have known that he was assuming the wrong circumference of the earth. A great visionary is something else though.

On this week's podcast I talk in detail again about Christopher Columbus' motivations and why he might just have been a religious fanatic after all. Have a listen! And if you want to read and hear more stories now, why not sign up for the Déjà Vu Story newsletter? There you will regularly receive your personal dose of history delivered directly to your mailbox. Blogs, podcasts, offers for books and more... I would be very happy to welcome you to the community!